How and Why Birds Sing

The Nine Most Important Things To Know About Bird Song

Songbirds have the chops

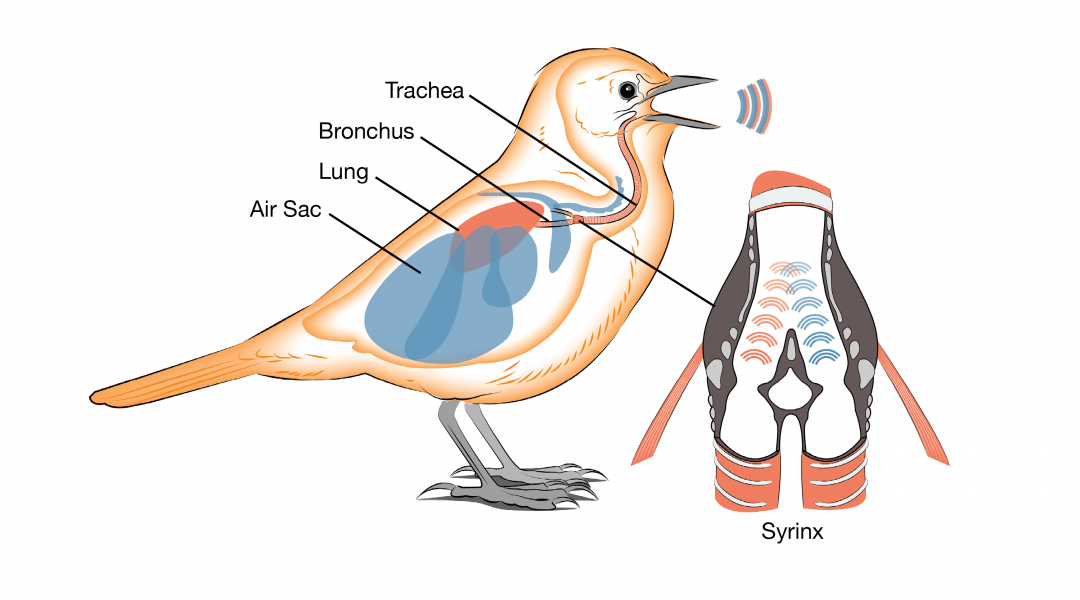

Songbirds learn their songs and perform them using a specialized voice box called a syrinxSEE-rinksthe bird voice box, located at the branch point between the trachea and bronchi and containing vibrating tissues called labia, in songbirds capable of making two sounds at once via independent muscle control. Vocally, they’re in a league of their own. These adaptations have been remarkably successful—songbirdsa species from the oscine (ah-SEEN) group of passerine (PASS-er-een) birds, songbirds (including sparrows, thrushes, and warblers) have a specialized voice box called a macsyrinx that can produce complex sounds, songbirds must learn their songs rather than developing them instinctively make up almost half of the world’s 10,000 bird species including warblers, thrushes, and sparrows. The vast majority of non-songbird species make simpler sounds that are instinctual rather than learned.

2. Birds sing to defend and impress

For a bird, singing can be draining. It is both energetically expensive and alerts predators. So then why do birds sing? Evidence suggests that in part, it is to proclaim and defend their territoriesin birds, the areas defended by males, pairs, or families as dedicated nesting sites and/or foraging areas. Studies have also shown that songs play a crucial role in attracting and impressing potential mates and may signal the overall health of the singer. As in humans, singing in birds is often a chance to show off.

3. Their repertoires include songs and calls

Why are some bird sounds referred to as songs and others as calls? Typically a song is defined as a relatively structured vocalization produced while attracting a mate or defending a territory. Calls tend to be shorter, less rhythmic sounds used to communicate a nearby threat or an individual’s location. Each species and individual has a variety of songs and calls used in different contexts that together make up its repertoirethe full range of sounds that an animal makes, each used in context to communicate specific messages. While the distinction between calls and songs is not always clear, it can be quite ear opening to explore the full repertoires of your favorite songbirds.

Song

Call

4. Hear a bird singing? It’s probably a male

Chances are when you hear a bird singing it’s a male. The majority of female songbirds in temperate zones use shorter, simpler callsin birds, a short simple vocal sound most often made to keep in touch and alert other birds while the males produce the longer and more complex vocalizations we think of as songin birds, a relatively complex learned vocalization that functions in mate attraction and territory defense. The story is different in the tropics where females commonly sing, and many species engage in duettingin birds, a coordinated set of vocalizations most often made by male-female pairs to maintain and strengthen their pair bond, more common in the tropics.

5. Songbirds are vocal gymnasts

The songbird syrinxSEE-rinksthe bird voice box, located at the branch point between the trachea and bronchi and containing vibrating tissues called labia, in songbirds capable of making two sounds at once via independent muscle control makes vocal gymnastics possible–for example the Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) is a able to sweep through more notes than are on a piano keyboard in just a tenth of a second. Because each branch of the songbird syrinx is individually controlled, the cardinal can start its sweeping notes with one side of the syrinx and seamlessly switch to the other side without stopping for a breath, making them the envy of human vocalists everywhere.

6. Some sing two notes at once

Unlike humans, birds produce vocal sounds using a syrinxSEE-rinksthe bird voice box, located at the branch point between the trachea and bronchi and containing vibrating tissues called labia, in songbirds capable of making two sounds at once via independent muscle control, an organ located where the trachea splits into two bronchial tubes. In songbirds, each side of the syrinx is independently controlled, allowing birds to produce two unrelated pitches at once. Some birds even have the ability to sing rising and falling notes simultaneously, like the Wood Thrush (Hylocichla mustelina) in its final trill. We can only imagine what musical heights human vocalists could reach with abilities like that.

7. Songbirds learn too

While some birds hatch knowing the songs they will sing as adults, the true songbirdsa species from the oscine (ah-SEEN) group of passerine (PASS-er-een) birds, songbirds (including sparrows, thrushes, and warblers) have a specialized voice box called a syrinx that can produce complex sounds, songbirds must learn their songs rather than developing them instinctively have to learn how to communicate effectively. Songbirds begin learning their songs while still in the nest, a phase known as the critical periodin songbirds, the time as a nestling during which the bird is most sensitive to learning the sounds of nearby birds, when nestlings listen to the adults singing around them. Following fledging, young birds attempt to replicate these songs, practicing until they have matched their tutor'sin songbirds which do not develop their songs instinctively, one of the adults that a young bird listens to as a nestling and models its adult song on song. Some songbirds, such as the catbirds, thrashers, and mockingbirds, learn to mimic other species—frogs, cats, and even car alarms.

8. Songbirds have local dialects

Just as humans have regional accents, some bird species develop distinct, area-specific dialectsa unique set of sounds made by a subpopulation of animals of the same species. Such variation in song often arises when populations of the same species are isolated by geographic features such as mountains, bodies of water, or stretches of unsuitable habitat. These local dialects are then passed on to the next generation of young birds, which hear the songs being performed by their father and other local males. After many generations, the birds from one area can sound quite different from those the next mountain over.

9. They sing at dawn (we’re not sure why)

Birds are often up before dawn singing their hearts out and adding their voices to the dawn chorusthe early morning singing event that songbirds from a variety of species participate in near sunrise, thought to help maintain male territories. But why do many species sing more intensely at dawn than they do at any other time of the day? Many of the songs heard at dawn are thought to function as warnings given by male birds in defense of their territory and mate. While the dawn chorus is a common phenomenon wherever birds live, little is known about why birds concentrate their efforts during these early hours.

Further Learning

Enjoy up-close portraits of birds in song with this interactive video collage.

Watch Songbirds in Action >Secrets To Understanding Song Patterns

A quick tutorial on sound visualization

Until you make a concerted effort to learn them, bird songs mostly go in one ear and right out the other. Since humans are such visual creatures, many people find that visualizations are the key to recognizing and remembering the unique voices of birds. Fortunately, there are tools that can visualize the properties of a sound—all you need to know is a little about how sound is produced.

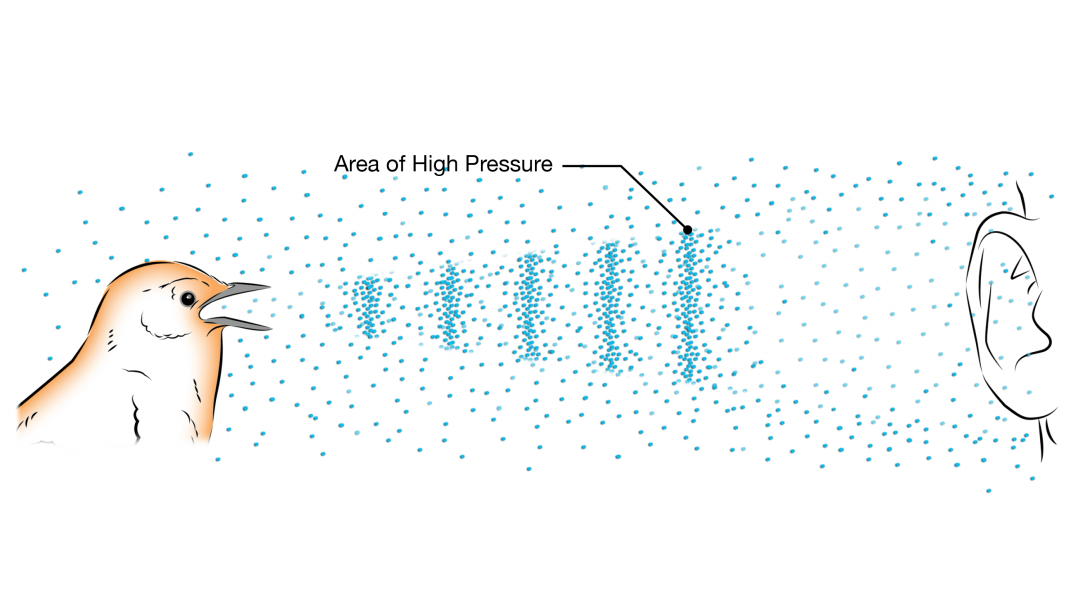

Sound is a pressure wave

Fundamentally, sound is the vibration of molecules. That’s why there’s no sound in space. Here on earth, air molecules that have been set into motion by a vibrating sound source—like bird’s voice box—bump into each other. This creates a cascade of movement that we call a pressure wave because it moves outward in bands of increased air pressure. Because your eardrum is sensitive to tiny differences in pressure, you detect the airborne vibrations that enter your ear as sound.

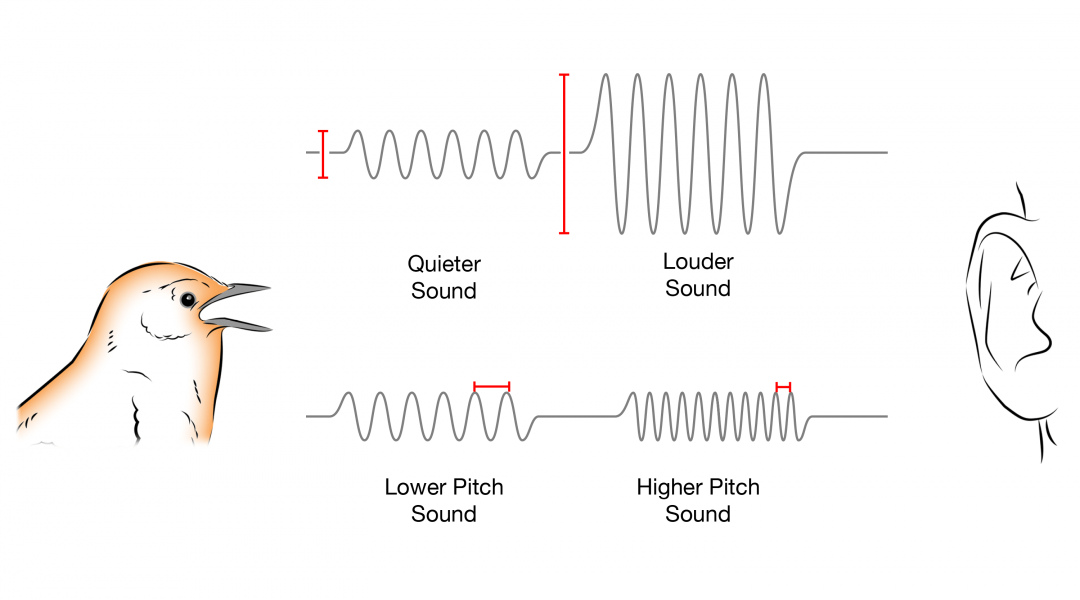

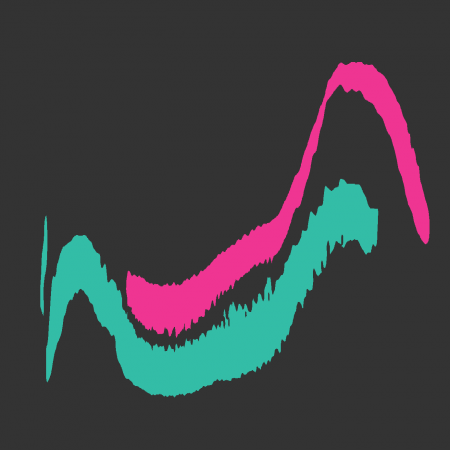

Waveforms: Seeing changes in loudness over time

Since we can’t see sound, it helps to find ways to visualize it. Waveformsfor sound, a graph displaying the change in air pressure (along the y-axis) over time (along the x-axis), the higher the air pressure the louder the sound, for example, show the peaks and lulls in air pressure over time—the higher the air pressure, the louder the sound. For simple sounds we can also see differences in pitch on the waveform—with more widely separated peaks indicating a slower-moving, longer-wavelength, lower-pitch sound.

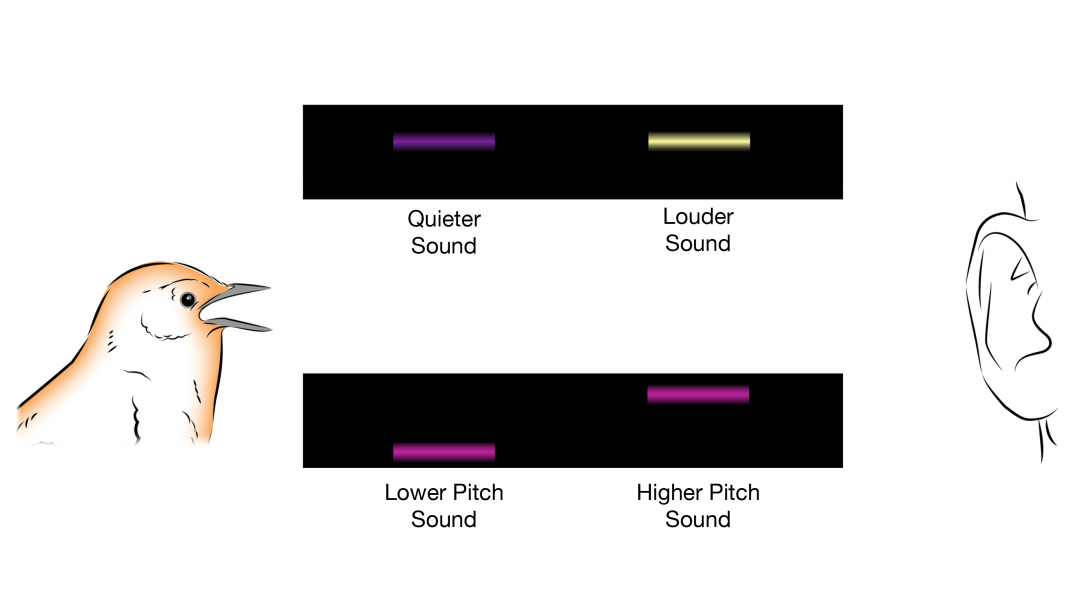

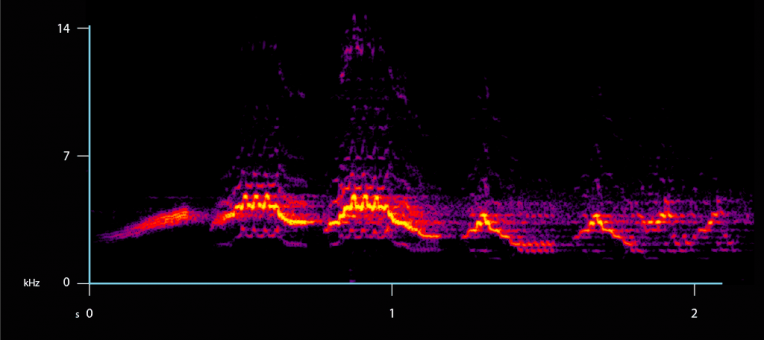

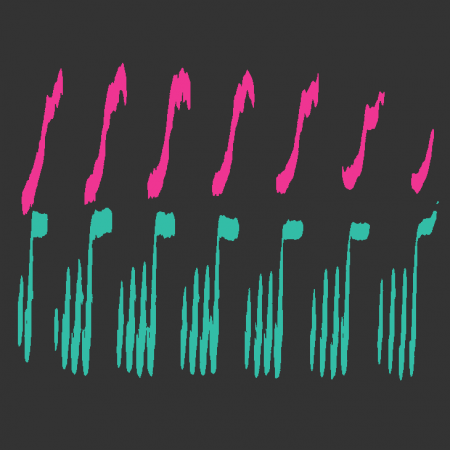

Spectrograms: Seeing changes in pitch and loudness over time

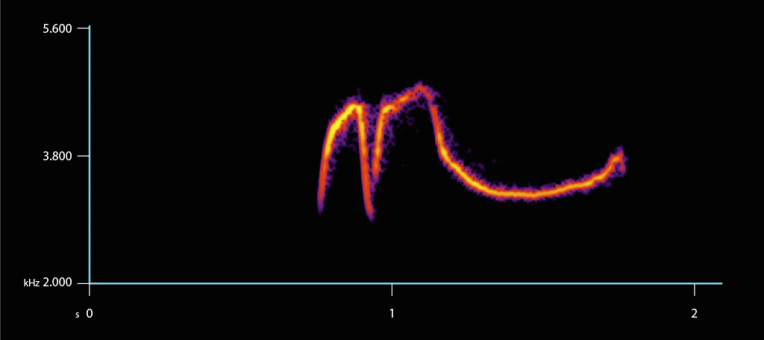

Spectrogramsfor sound, a graph displaying the changes in pitch (along the y-axis) and loudness (in color intensity) over time (along the x-axis) add another very helpful dimension to sound visualization by showing changes in pitch and loudness over time. Spectrograms can come in many colors, but typically the brighter the color, the louder the sound.Seeing the beauty in bird song

Spectrograms allow you to see song patterns at a glance. The Eastern Wood-Pewee (Contopus vireos) sings such a high-pitched whistle that it can be hard to recognize the pattern by ear—but the “M” shape it makes on a spectrogram is unforgettable.

Spectrograms can also reveal hidden complexities in bird song. The Veery (Catharus fuscescens) sings an otherworldly song that can be appreciated even more when seen on a spectrogram. When you look closely, you see that the Veery strings together pitch sweeps and mini-trills to create its impressive flutelike vocal effects.

Listen to the Veery at normal speed:

The Veery song is even more interesting at quarter speed:

Further Learning

The game that trains your brain to see sound and learn bird song.

Play Bird Song Hero >Animated scientific illustrations bring learning to life.

Download the Complete Set >Make your own spectrograms with Raven Lite.

Download Raven Lite >How Birds Sing: the Amazing Syrinx

songbirdsa species from the oscine (ah-SEEN) group of passerine (PASS-er-een) birds, songbirds (including sparrows, thrushes, and warblers) have a specialized voice box called a syrinx that can produce complex sounds, songbirds must learn their songs rather than developing them instinctively have evolved a specialized two-sided vocal organ called the syrinxSEE-rinksthe bird voice box, located at the branch point between the trachea and bronchi and containing vibrating tissues called labia, in songbirds capable of making two sounds at once via independent muscle control that allows them to perform impressive feats of vocal gymnastics—including the unique ability to create two unrelated pitches at once.Here are some examples of how birds use their syrinx to produce impressive sounds.

More pitches than a piano

How does the Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) span a wider range of pitches than a piano in just a tenth of a second? Remarkably, the secret to the Northern Cardinal’s vocal prowess has been measured in the lab.1 It turns out that these vocal gymnastics are made possible by a seamless switch between sides of the syrinxSEE-rinksthe bird voice box, located at the branch point between the trachea and bronchi and containing vibrating tissues called labia, in songbirds capable of making two sounds at once via independent muscle control partway through the cardinal’s most dramatically sweeping notes.

Northern Cardinal

Speedy trills

There’s more to the domestic Island Canary’s (Serinus canaria forma domestica) delicate song than meets the human ear. In the well-studied “A syllable” trillin birds, an uninterrupted note made of repeating elements produced at high speed, often at a stable pitch the male canary alternates between high and low notes by rapidly switching sides of the syrinxSEE-rinksthe bird voice box, located at the branch point between the trachea and bronchi and containing vibrating tissues called labia, in songbirds capable of making two sounds at once via independent muscle control—all without taking a breath. Performing these trills well can pay off. Studies have shown that female canaries consistently prefer males who sing faster and with a wider range of pitches.2

Domestic Canary

Two notes at once

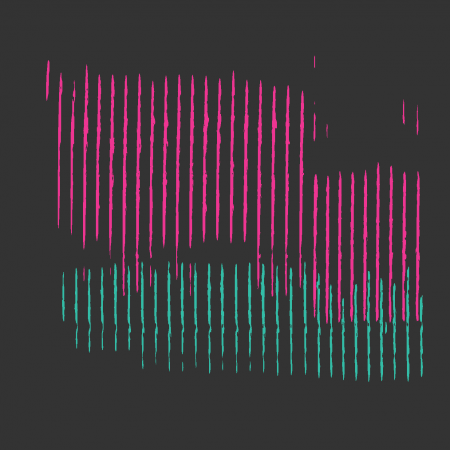

With over 1,000 song types, the Brown Thrasher (Toxostoma rufum) has one of the largest repertoiresthe full range of sounds that an animal makes, each used in context to communicate specific messages in the bird world. As part of that incredible variety, the thrasher sometimes sings two sweeping tones at the same time—a feat made possible by its two-sided vocal organ. By controlling each side of the syrinxSEE-rinksthe bird voice box, located at the branch point between the trachea and bronchi and containing vibrating tissues called labia, in songbirds capable of making two sounds at once via independent muscle control independently, thrashers create unique sounds that only a bird has the ability to produce.

Brown Thrasher

The ultimate trill

The Wood Thrush (Hylocichla mustelina) song ends with one of the most complex sounds a bird can create. Layered above a series of lower-pitch mini-trills is a series of higher-pitch sweeping tones. To perform this impressive trillin birds, an uninterrupted note made of repeating elements produced at high speed, often at a stable pitch the bird must pair impeccably timed breath control with independent muscle movements on each side of the syrinxSEE-rinksthe bird voice box, located at the branch point between the trachea and bronchi and containing vibrating tissues called labia, in songbirds capable of making two sounds at once via independent muscle control.

Wood Thrush

Further Learning

Animate the bird voice box and hear the impressive results.

Animate the Syrinx >Animated scientific illustrations bring learning to life.

Download The Complete Set >Practice, Perfect: How Birds Learn Songs

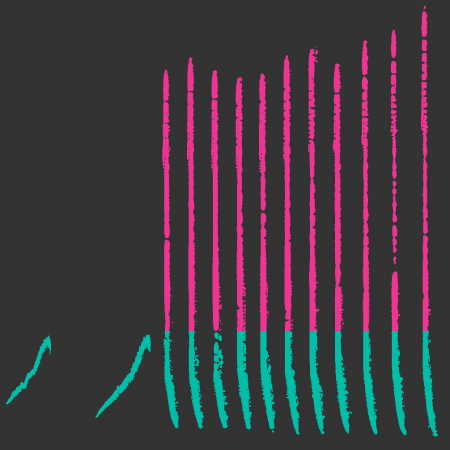

Songbirds listen, learn, and practice a lot like we do. As nestlings they tune in to neighborhood songs by listening closely and committing them to memory. It is only later, after they’ve fledged, that young birds begin to practice. The early practice songs are messy and unstructured, a lot like the babblingin humans, to practice talking by stringing together sounds, as babies do before they can produce clear words or sentences, analogous to plastic song in songbirds of a young child. After many months of practice, songbirds refine their songs and settle on a repertoire, which often stays fixed for the rest of their lives.

Songbirds need tutors too

Sparrows are famous songsters. They’ve been well studied and have taught us much about the song learning process.3 Like many songbirdsa species from the oscine (ah-SEEN) group of passerine (PASS-er-een) birds, songbirds (including sparrows, thrushes, and warblers) have a specialized voice box called a syrinx that can produce complex sounds, songbirds must learn their songs rather than developing them instinctively, sparrow nestlings listen closely to nearby males and then use these tutorin songbirds which do not develop their songs instinctively, one of the adults that a young bird listens to as a nestling and models its adult song on songs as templates for their own songs. If you remove a young sparrow from his nest and isolate him from tutors, he will never develop normal (or crystallizedin birds, one of the songs that songbirds settle on after learning and practicing, often remaining constant in adulthood) adult song.

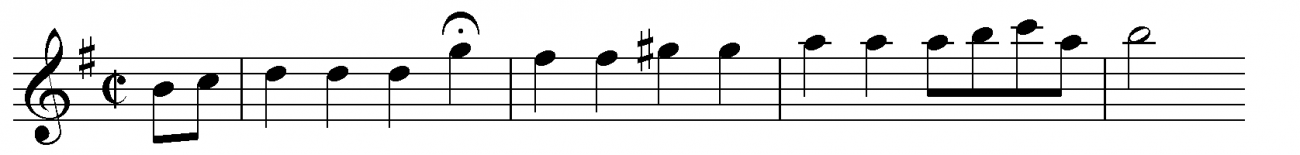

Plastic song of a young White-throated Sparrow:

Crystallized song of an adult White-throated Sparrow:

Practice makes perfect

Carolina Wren by Joey Herron

Many songbirds are prolific singers. Carolina Wrens (Thryothorus ludovicianus) repeat the same song hundreds of times before moving to the next song in their large repertoiresthe full range of sounds that an animal makes, each used in context to communicate specific messages. Becoming an accomplished performer requires a focused period of song learning (sensory periodin songbirds, the early months of life before they practice singing that they most easily learn the songs of nearby tutors) and an intensive period of practice (sensorimotor periodin songbirds, the period during which the bird practices its song, usually following fledging). For most songbirds these are distinct learning phases: (1) as nestlings, birds memorize the songs of their neighborhoodsin birds, the set of adjacent territories or display sites surrounding a focal territory or site>; then (2) as juveniles, they move to a new territory and practice those songs until they can masterfully defend a territory.

This practicing Carolina Wren is starting to get into the rhythm, but still needs some practice before it’s perfect

Plastic song of a young Carolina Wren

Recording by Paul Driver

Here’s an adult Carolina Wren song, with its precise rhythm perfected.

Crystallized song of an adult Carolina Wren

Recording by Wil Hershberger/Macaulay Library ML#94253

Eavesdropping is best

You can learn an awful lot from what you overhear. Birds can too. In fact, research on Song Sparrows (Melospiza melodia) has revealed that young males learn more from listening in on interactions among neighborhoodin birds, the set of adjacent territories or display sites surrounding a focal territory or site males than from solo tutorin songbirds which do not develop their songs instinctively, one of the adults that a young bird listens to as a nestling and models its adult song on performances. This may seem surprising at first, but there is a lot more information packed into a heated exchange than a solo, including cues about which song patterns and singing strategies are most winning. This is crucial know-how: the birds most successful at defending territories are those whose song types (adults learn up to 13 separate types) most accurately match the various songs of their neighbors.4

All the elements are here for this young Song Sparrow; he just needs to get them in the right order.

Plastic song of a young Song Sparrow

Recorded by Chris Templeton

Here, the same Song Sparrow has grown up a bit and finally mastered the crystallized adult form of this song.

Crystallized song of an adult Song Sparrow

Recorded by Chris Templeton

Not a true songbird, but still learns its song

Along with parrots and bellbirds, hummingbirds are one of the rare bird groups that learn their songs even though they are not true songbirdsa species from the oscine (ah-SEEN) group of passerine (PASS-er-een) birds, songbirds (including sparrows, thrushes, and warblers) have a specialized voice box called a syrinx that can produce complex sounds, songbirds must learn their songs rather than developing them instinctively—a good example of how learning can evolve multiple times from different ancestors.5 The Little Hermit (Phaethornis longuemareus) is a tiny hummingbird that uses its song to attract females at display sites in tropical South America. Each Little Hermit sings in a local dialecta unique set of sounds made by a subpopulation of animals of the same species very similar to his direct neighbors but quite different from more distant birds.

This Little Hermit’s early song is simpler than what he’ll sing as an adult.

Plastic song of a young Little Hermit:

Recorded by Julian Kapoor

This is the same Little Hermit months later: he sings a more complex song the same way each time.

Crystallized song of an adult Little Hermit

Recorded by Julian Kapoor

Learning like the birds

Songbirds and humans have a lot in common on the learning front. Baby birds babblein humans, to practice talking by stringing together sounds, as babies do before they can produce clear words or sentences, analogous to plastic song in songbirds just as humans do. Like birds, humans need to hear themselves and others in order to produce normal adult sounds. And just as it is much harder for us to learn languages after childhood, most birds experience a critical periodin songbirds, the time as a nestling during which the bird is most sensitive to learning the sounds of nearby birds as nestlings when they are best able to learn song. There is even recent evidence that some songbirds can learn syntaxa particular ordering of vocalizations that produces a specific meaning in a similar way to how we learn to string together sentences.6

Listen as this two-year-old learns the ABCs.

Plastic song of a young child

Recorded by a proud parent

Now for a jazzy grown up version by musician Nate Marshall.

Crystallized (and jazzy) song of a adult musician:

Recorded by Mya Thompson

Further Learning

Compare learning juveniles and seasoned adult songbirds side-by-side

Hear Practice vs. Perfect >The Music of Bird Song

Songbirds—with their two-sided voice boxes and capacity to learn complicated songs—create soundscapes that have influenced many composers and instrumentalists. Bird melodies have been recreated by flutes, oboes, pianos, and xylophones in musical works from Haydn’s The Seasons to Beethoven’s sixth symphony.

Birds particularly fascinated Mozart, who kept a starling as a pet. According to one of his journals, he even taught the bird to sing the opening theme of one of his piano concertos (though it apparently always sang sharp.) This claim is believable as starlings are fantastic mimics, often boasting repertoires of 15–20 distinct imitations. Some are of different birds; others are of manmade sounds such as cars, whistles, and even human speech.

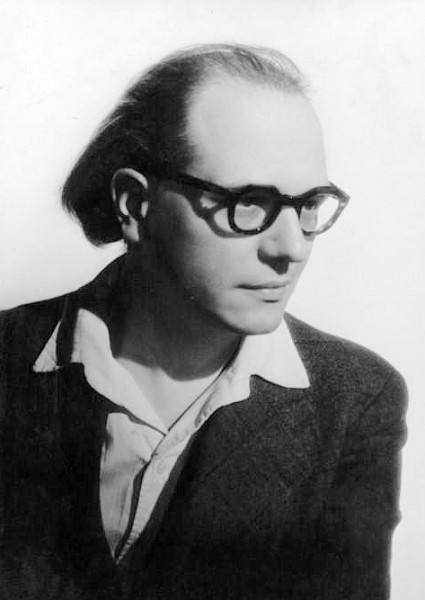

One of the composers most captivated by birds was Olivier Messiaen. During the twentieth century he produced orchestral, choral, and piano pieces made up of individual bird songs reproduced by different instruments. This eventually led him on a quest around the world to observe and transcribe the songs of exotic birds. Messiaen later used these records in the creation of several compositions including the orchestral work Oiseaux Exotiques, which features the songs of the White-crested Laughingthrush, the bulbul, and 45 other unique bird species.

Now, decades after Messiaen’s final composition, with advanced recording equipment readily available, musicians can more easily incorporate bird vocalizations directly into their work. Contemporary composers have used bird song recordings to overlay orchestral symphonies and choral performances. Pierre Henry and Pierre Schaeffer’s electronic creation, Gene Piece, R.A.I. Bird is created entirely through electronic manipulation of bird sounds. Other contemporary musicians continue the tradition of using instruments to mimic bird song, like jazz composer Maria Schneider in her album Cerulean Skies. It’s because the bird soundscape can be so varied and complex that songbirds have captured the attention of music lovers through the ages.

Further Learning

Join Grammy-recognized artists Maria Schneider and Theo Bleckmann in their musical experiment to help us tune in to nature’s music.

Watch Birds Got Swing >References

- Suthers, R. A. & Goller, F. (1997) Motor correlates of vocal diversity in songbirds. In: Current Ornithology. Nolan Jr., V., Ketterson, E. &Thompson, C. F. (Eds.). New York, Plenum Press. 14: 235-288.

- Suthers, R. A., Vallet, E. & Kreutzer, M. (2012) Bilateral coordination and the motor basis of female preference for sexual signals in canary song. Journal of Experimental Biology. 215: 2950-2959.

- Beecher, M. D. (2008) Function and mechanisms of song learning in song sparrows. Advances in Animal Behavior, 38: 167-225.

- Templeton, C. N., Akçay, Ç., Campbell, S. E. & Beecher, M. D. (2009) Juvenile sparrows preferentially eavesdrop on adult song interactions. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B. 277: 447-453.

- Araya-Salas, M. , Wright, T. (2013) Open-ended song learning in a hummingbird. Biology Letters, 9: 20130625.

- Brainard, M.S. & Doupe, A.J. (16 May 2002) What songbirds teach us about learning. Nature, 417: 351-358.

Suggested citation: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 2014. Bird Song. All About Bird Biology <birdbiology.org>. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. <add date accessed here: e.g. 02 Oct. 2014>.

Acknowledgements:

Authors: Mya Thompson and Annalyse Moskeland

Web Designer: Jeff Szuc

Web programmer: Tahir Poduska

Illustrator: Andrew Leach