A Canyon of Their Own—A Preserve for Tufted Jays in Mexico

by George Oxford Miller

July 15, 2009

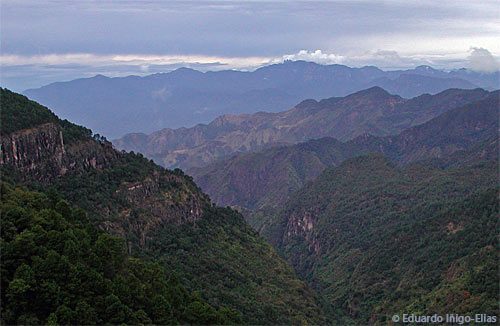

Our bus drives ever higher into Mexico’s rugged Sierra Madre Occidental, squeezing around tight mountain curves with heart-thumping drop-offs. We dodge sluggish trucks that sweep the road from shoulder to shoulder and pass villages not much more than a road sign and two or three houses. In the last two hours, the vegetation has changed from the coastal plains and thorn forest around Mazatlan, Mexico, to tropical deciduous forest. Now, we cross the Tropic of Cancer at 6,500 feet elevation and climb into a woodland of oaks and pines. A dense canopy blankets the steep slopes and towering ridges.

Suddenly our driver, Walter Bishop, slams on the brakes and veers off the road. “Tufted Jays!” he yells.

Conversation stops, and we grab our binoculars and hurry off the bus. “One flew across the road,” Walter says. “There’s probably more.” Since Tufted Jays(Cyanocorax dickeyi) travel in flocks, seeing one usually means more of the noisy, energetic birds are nearby.

We scan the trees and begin calling out sightings. The flamboyant birds careen through the treetops like beach balls on a windy day. To our good fortune, about a dozen forage in the oaks and pines close to the road. Soon we’re watching a pair full-frame in our spotting scope. The birds are feeding in a bromeliad, an air plant, growing on a massive oak. They probe the airy cluster of holdfasts, roots, and leaves, searching for delectable insects then move on to another clinging plant.

“Tufted Jays were the last bird discovered in Mexico,” Peter Alden, our leader and author of Finding the Birds of Western Mexico, tells us. “They were hidden in the mountains until the road from Mazatlan to Durango was cut through in the 1930s. They only occur in a few forested areas in the Sierra Madre Occidental.”

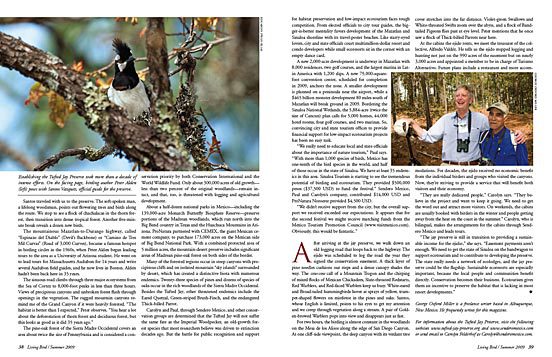

Our daytrip to the Tufted Jay Preserve, a few miles farther down the road, was part of the first Mazatlan Bird Festival, held in January 2009. Sendero Mexico, a private nature tour company specializing in birding tours, and ProNatura Noroeste, the oldest and largest conservation organization in Mexico, organized the festival. The event offered four days of local birding, workshops, and programs focusing on conservation in northwestern Mexico. Trips to the Tufted Jay Preserve were one of the highlights of the event.

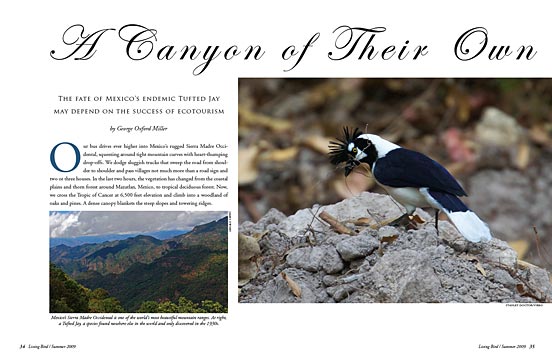

As recently as 2004, the survival of the Tufted Jay, one of the most dazzling members of the Corvidae family, was in jeopardy. The crested black, white, and blue birds, called “Chara Pinta” in Spanish, live only in the deep canyons and rugged slopes of the pine-oak forests in a limited area of the Sierra Madre Occidental. None of their habitat was protected; all was subject to local logging. The creation of the preserve illustrates the critical role ecotourism can play in establishing economically sustainable preserves—not just in Mexico but in communities economically dependent on natural resources around the world.

The Mazatlan Bird Festival brought together the key players in the effort to preserve threatened ecosystems in the state of Sinaloa, which borders the Sea of Cortez, one of the country’s most rapidly developing regions. For the evening programs, Gustavo Daneman, executive director of ProNatura Noroeste, outlined the group’s regional goals and priority projects. Ernesto Enkerlin, executive director of the National Commission for Protected Natural Areas, described government efforts to identify and preserve threatened habitat. Peter Alden, the keynote speaker, stressed the importance of bird and nature tourism in Mexico and led field trips.

Establishing the jay preserve took more than a decade of efforts by individuals and the major conservation groups in Mexico. “Paul and I first visited the area with the Tufted Jays in 1997 and realized that the highly endemic species was probably threatened,” says Carolyn Felderhof, a birding tour leader who cofounded Sendero Mexico with her husband, Paul Beckman.

The movement gained momentum in 1999 when Sendero Mexico sponsored a bird photography expedition with Doug Wechsler of Visual Resources for Ornithology at Philadelphia’s Academy of Natural Sciences. In 2001, they invited Patricio Robles Gil, president of Unidos para Conservacion, and ornithologist and wildlife artist Hans Peeters to visit the preserve. To help raise awareness and support, the Mexican Postal Service released a Tufted Jay commemorative stamp illustrated by Peeters. In 2004, five Cornell Lab of Ornithology staff visited the proposed preserve with ProNatura and helped publicize the efforts in a BirdScopearticle.

One factor that affects conservation in Mexico is the collective ownership of land, which dates back to the revolution. Eighty percent of the nation’s land belongs to “ejidos”—groups of families whose livelihood depends on the natural resources of their communal holdings. The Tufted Jay habitat lies in the heart of El Palmito Ejido, a 12,355-acre holding managed by 64 families. The area encompasses two deep canyons and rocky ridges covered with pine-oak forest: prime Tufted Jay habitat. For the 900 people who depend on money earned by logging, removing the canyons from their income-producing acreage is not an option

ProNatura opened an office in Mazatlan in 1997 with their low-impact Tourism for Conservation Program as a major emphasis. The Tufted Jay Preserve became a priority project. With a mission similar to that of The Nature Conservancy in the United States, ProNatura works with ejidos, private landowners, and industry to purchase land and arrange conservation agreements. They have protected 642,474 acres in Mexico, including 18,285 acres of wetlands and lagoons for wintering and nesting shorebirds and waterfowl in Sinaloa.

As interest in the jay preserve increased, ProNatura and Sendero Mexico began discussions with El Palmito Ejido about setting aside a conservation easement. Finally, in December 2005, ProNatura and the National Commission for the Use and Knowledge of Biodiversity (CONABIO) contracted with the ejido to cease logging in the 990 acres that encompass San Diego and Rancho Liebre canyons. In return, the collective will receive regular payments for 30 years.

In 2006, Paul Beckman worked with the Forestry Department and secured a grant for the ejido to develop the road into the preserve and to build two cabins, each with two bedrooms, a kitchenette, and hot running water. The National Commission of Protected Natural Areas provided additional funding to build two more cabins, construct trails, and train community members to act as guides.

“Operating an ecotourism business is new to the group,” Carolyn emphasizes. “They need training and support. But the real success story is Santos Vazquez, the official guide for the preserve, who is a member of El Palmito Ejido. He spent his life logging and received a lot of pressure to keep it going, but he recognized the damage to the habitat and decided to support the conservation easement. Now he’s one of the best birders in the area.”

Santos traveled with us to the preserve. The soft-spoken man, a lifelong woodsman, points out flowering trees and birds along the route. We stop to see a flock of chachalacas in the thorn forest, then transition into dense tropical forest. Another five-minute break reveals a dozen new birds.

The mountainous Mazatlan-to-Durango highway, called “Espinazo del Diablo” (Devil’s Backbone) or “Camino de Tres Mil Curvas” (Road of 3,000 Curves), became a famous hotspot in birding circles in the 1960s, when Peter Alden began leading tours to the area as a University of Arizona student. He went on to lead tours for Massachusetts Audubon for 14 years and write several Audubon field guides, and he now lives in Boston. Alden hadn’t been back here in 35 years.

The sinuous road climbs through three major ecosystems from the Sea of Cortez to 8,000-foot peaks in less than three hours. Views of precipitous canyons and unbroken forest flash through openings in the vegetation. The rugged mountain canyons remind me of the Grand Canyon if it were heavily forested. “The habitat is better than I expected,” Peter observes. “You hear a lot about the deforestation of thorn forest and deciduous forest, but this looks as good as it did 35 years ago.”

The pine-oak forest of the Sierra Madre Occidental covers an area about twice the size of Pennsylvania and is considered a conservation priority by both Conservation International and the World Wildlife Fund. Only about 300,000 acres of old growth—less than two percent of the original woodlands—remain intact, and that, too, is threatened with logging and agricultural development.

About a half-dozen national parks in Mexico—including the 139,000-acre Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve—preserve portions of the Madrean woodlands, which run north into the Big Bend country in Texas and the Huachuca Mountains in Arizona. ProNatura partnered with CEMEX, the giant Mexican cement company, to purchase 173,000 acres on the Mexican side of Big Bend National Park. With a combined protected area of 5 million acres, the mountain-desert preserve includes significant areas of Madrean pine-oak forest on both sides of the border.

Many of the forested regions occur in steep canyons with precipitous cliffs and on isolated mountain “sky islands” surrounded by desert, which has created a distinctive biota with numerous endemics. Twenty-three species of pines and dozens of species of oaks occur in the rich woodlands of the Sierra Madre Occidental. Besides the Tufted Jay, other threatened endemics include the Eared Quetzal, Green-striped Brush-Finch, and the endangered Thick-billed Parrot.

Carolyn and Paul, through Sendero Mexico, and other conservation groups are determined that the Tufted Jay will not suffer the same fate as the Imperial Woodpecker, an old-growth forest species that most researchers believe was driven to extinction decades ago. But the battle for public recognition and support for habitat preservation and low-impact ecotourism faces tough competition. From elected officials to city tour guides, the bigger-is-better mentality favors development of the Mazatlan and Sinaloa shoreline with its travel-poster beaches. Like starry-eyed lovers, city and state officials court multimillion-dollar resort and condo developers while small ecoresorts sit in the corner with an empty dance card.

A new 2,000-acre development is underway in Mazatlan with 8,000 residences, two golf courses, and the largest marina in Latin America with 1,200 slips. A new 79,000-square-foot convention center, scheduled for completion in 2009, anchors the zone. A smaller development is planned on a peninsula near the airport, while a $465 billion monster development 80 miles south of Mazatlan will break ground in 2009. Bordering the Sinaloa National Wetlands, the 5,884-acre (twice the size of Cancun) plan calls for 5,000 homes, 44,000 hotel rooms, four golf courses, and two marinas. So, convincing city and state tourism offices to provide financial support for low-impact ecotourism projects has been no easy task.

“We really need to educate local and state officials about the importance of nature tourism,” Paul says. “With more than 1,000 species of birds, Mexico has one-tenth of the bird species in the world, and half of those occur in the state of Sinaloa. We have at least 35 endemics in this area. Sinaloa Tourism is starting to see the tremendous potential of birding and ecotourism. They provided $500,000 pesos ($37,500 USD) to fund the festival.” Sendero Mexico, Paul and Carolyn’s company, contributed $14,000 USD and ProNatura Noroeste provided $4,500 USD.

“We didn’t receive support from the city, but the overall support we received exceeded our expectations. It appears that for the second festival we might receive matching funds from the Mexico Tourism Promotion Council. Obviously, this would be fantastic.”

After arriving at the jay preserve, we walk down an old logging road that loops back to the highway. The ejido was scheduled to log the road the year they signed the conservation easement. A thick layer of pine needles cushions our steps and a dense canopy shades the way. The cow-cow call of a Mountain Trogon and the chirping of mixed flocks of Mexican Chickadees, Slate-throated Redstarts, Red Warblers, and Red-faced Warblers keep us busy. White-eared and Broad-tailed hummingbirds hover at sprays of yellow, trumpet-shaped flowers on mistletoe in the pines and oaks. Santos, whose English is limited, points to his eyes to get my attention and we creep through vegetation along a stream. A pair of Golden-browed Warblers pops into view and disappears just as fast.

For two hours, the birding is almost constant in the woodlands on the Mesa de los Alisos along the edge of San Diego Canyon. At one cliff-side viewpoint, the deep canyon with its verdant tree cover stretches into the far distance. Violet-green Swallows and White-throated Swifts zoom over the abyss, and a flock of Band-tailed Pigeons flies past at eye level. Peter mentions that he once saw a flock of Thick-billed Parrots near here.

At the cabins the ejido rents, we meet the treasurer of the collective, Alfredo Valdéz. He tells us the ejido stopped logging and hunting not just on the 990 acres of the easement but on nearly 3,000 acres and appointed a member to be in charge of Turismo Alternativo. Future plans include a restaurant and more accommodations. For decades, the ejido received no economic benefit from the individual birders and groups who visited the canyons. Now, they’re striving to provide a service that will benefit both visitors and their economy.

“They are really dedicated people,” Carolyn says. “They believe in the project and want to keep it going. We need to get the word out and attract more visitors. On weekends, the cabins are usually booked with birders in the winter and people getting away from the heat on the coast in the summer.” Carolyn, who is bilingual, makes the arrangements for the cabins through Sendero Mexico and leads tours.

“The jay preserve is still in transition to providing a sustainable income for the ejidio,” she says. “Easement payments aren’t enough. We need to get the state of Sinaloa on the bandwagon to support ecotourism and to contribute to developing the preserve. The state really needs a network of ecolodges, and the jay preserve could be the flagship. Sustainable ecoresorts are especially important, because the local people and communities benefit directly. Conservation becomes their business. Ecotourism gives them an incentive to preserve the habitat that is lacking in most resort developments.”

George Oxford Miller is a freelance writer based in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He frequently writes for this magazine.

All About Birds

is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you

American Kestrel by Blair Dudeck / Macaulay Library