Making a Case for Open Access

On October 28th, the global scientific community wrapped up the Open Access Week. Open Access Week (according to wikipedia, and fact-checked by openaccessweek.com) is a scholarly communication event that focuses on Open Access and related topics. Events include talks, digital seminars, symposia, curated blog communities, or the announcement of open access mandates or other milestones in open access. All free of charge, of course.

This is well and good (very good in my opinion), but what is Open Access and why should you care about it?

First and foremost Open Access means information that is freely available to anyone who seeks it. It refers, mostly, to published academic literature (papers, theses, book chapters, that sort of thing), but also to datasets that people generate as they do research.

For folks outside of academic publishing, it can seem a bit obtuse the way we share the results of our studies. We conduct research, that in many cases takes years to produce (decades in some cases). Once we’ve processed, analyzed, and written our report we then publish manuscripts in society journals (for example in my case the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, or Marine Mammal Science). For publishing this manuscript (here’s where the non-scientists cringe) we receive no compensation; indeed in many cases we are charged Article Processing Charges or APCs for short. Further, for folks who want to read the literature we’ve just produced traditionally they, or their institution, are required to pay a subscription fee. Harvard University, for example is billed $3.5 million a year to cover the cost of journal access. The price for knowledge can be exorbitant.

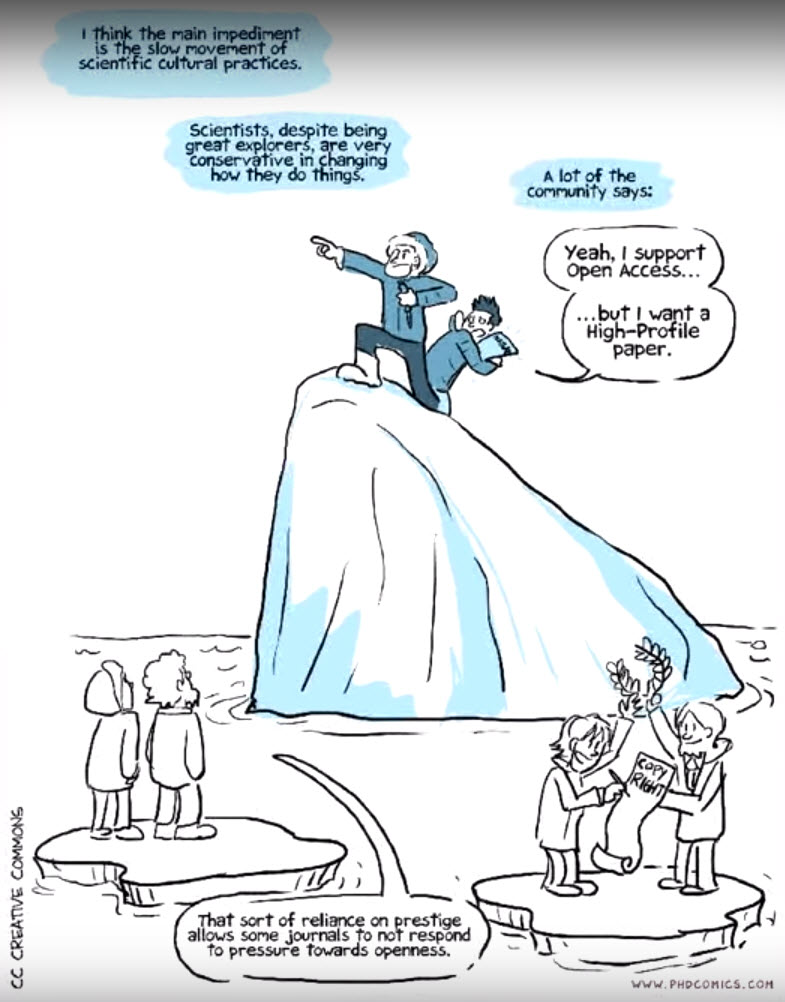

Enter Open Access. Open Access publishing is a movement within the academic community to publish studies that are freely available and distributable without the need for a fee based subscription. The underlying ethos is that information should be available to those who need it. In this regard academia is beginning, albeit slowly, to catch up to a shifting cultural baseline.

The sharing of information is ingrained in the modern technological world. I can freely download secret family recipes, instructions on how to change a flat tire, poems by E.E. Cummings and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, or algebraic proofs. I cannot however, without some sort of institutional login, freely download peer reviewed literature on the media’s influence (or lack thereof) on frequent dieting in adolescent girls. Why? Cookies are free, but legitimate studies on social pressures and health is available only to those affiliated with an institution? Without pointing fingers, it is time for the research community to shift our own culture, and value the dissemination of work above all. Open access allows us, as a scientific community, to make a commitment to minimizing access disparity, and maximizing access to merit based research across subjects. This is true for readers both within and beyond the academic community. One of the often touted benefits of Open Access publishing is that the general public has access to primary literature, regardless of race, religion, or socioeconomic status.

But Open Access publishing is only the first step. Opening the front door is not the same as giving someone directions to the house.

Open access publications ensure equal access. But equality and equity are not equivalent. Equality is about sameness – everyone gets to read the paper. Equity is about fairness – each person has the ability to find, and also understand the paper. As researchers we have developed a vocabulary that we’ll gently call ‘inaccessible’ to many, if not most. This phenomenon is so widespread that without batting an eyelash we’ll ask a scientist to quickly summarize their work for ‘non-specialists’, with the cogent implication that this means simplifying it to the utmost. While the vocabulary of research is to a large degree topically specific (one cannot talk about osmosis without using the word ‘osmosis’ at least once), the language of research has grown so obtuse that we ask “Do elasmobranchs possess the cognitive ability to discriminate between complex auditory cues?” rather than asking “can a shark tell the difference between two types of music?” (You can read this compelling study here, for a subscribers fee). I feel quite confident that my grandmother understands what it means to play music to sharks, but complex auditory cues may not get much of a reaction.

So yes, open access publishing levels the accessibility playing field (this is the equality portion of publishing). However, publishing research in an open access journal does little to increase the scope of dissemination to the members in our global community who may most benefit from the information (this is the equity part of the conversation). We have some choices to make. Is equity important enough to us as a community that we will shift both our language and our access? Do we cultivate a research culture in which every scientific manuscript is accompanied by straightforward translation? If I can successfully write an entire manuscript in “layman’s english” will my peer reviewers accept it? Let us not be fooled into thinking that shifting the culture of science is a swift process.

Albert Einstein wrote “Everybody is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.” As a research community we are moving in the right direction, but let us do more than remove all of the fences from the trees and post signs that say “Climb me”. Let’s examine how we can be better communicators of our work, both in the peer review literature and beyond it.

Acknowledgements:This blog is made possible by the support from PhDcomics.com