From Birds to Forests: A Decades-Long Effort to Protect the World's Third Largest Rainforest

“What happens to the intact Indo-Pacific forests between now and 2030 will not only determine the future of the people and wildlife that live there, it will affect the future for all of us on planet Earth.”

— Dr. Edwin Scholes, Birds-of-Paradise Project Leader

Since 2009, the Cornell Lab has inspired people across the world with high-quality footage of the birds-of-paradise in New Guinea and surrounding areas. But what began as an effort to document these stunning birds for research and education has since pivoted to helping stakeholders to protect their forest habitats, which are at risk of disappearing but have received much less attention than the world’s other major rainforests. The Center for Conservation Media brings its commitment to addressing the climate and biodiversity crises to support conservation partners’ efforts to safeguard forest systems and human livelihoods.

RECENT NEWS: Celebrating groundbreaking progress and opportunities in the world’s third largest rainforest at the 2024 New York Climate Week.

A day-long event at New York Climate Week convened participants and audiences at Cornell University’s NYC Conference Center to celebrate a decade of declining deforestation in Indonesia and to discuss how the international community can support these achievements going forward. The agenda also included an exploration of the ways Indonesia’s successes might extend to the other great global rainforests.

Alongside high-level representatives from the Provincial Government of West Papua, leaders from Indonesian NGOs and global partners joined voices with prominent speakers including Lord Zac Goldsmith (Senor Fellow at the Bezos Earth Fund), Razan Al Mubarak (President of IUCN & UN Climate Change High Level Champion), Ani Dasgupta (President & CEO of the World Resources Institute) and Norwegian Ambassador Hans Brattskar (Special Envoy on Climate and Forest).

Indonesia has done something really remarkable…if other great forest nations had behaved in the manner that Indonesia has, then the whole discussion we’re having here across climate would be very different.

Lord Zac Goldsmith, Senior Fellow Bezos Earth Fund

I’m incredibly grateful that Indonesia’s achievements are being acknowledged on such an important platform.

Prof. Dr. Ir. Siti Nurbaya, Minister for Environment and Forestry, Republic of Indonesia

This event was hosted by the World Resources Institute, International Union for the Conservation of Nature and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology in partnership with the Climate and Land Use Alliance, the EcoNusa Foundation, the Rekam Nusantara Foundation and the Provincial Government of West Papua.

Rekam Nusantara, premiered their film on the cultural importance of forests (a Cornell Lab co-production), during the event:

In the weeks following the event celebrating Indonesia’s achievements, Indonesia’s Minister for Environment and Forestry, Prof. Dr. Ir. Siti Nurbaya, announced a huge new National Park in Papua, the Mamberamo Foja National Park.

As Indonesia’s 57th National Park, it covers more than 1.7m hectares of intact and critically important ecosystems. It is home to 35 Indigenous tribes whose stewardship has maintained the area one of the most biodiverse places on Earth. Highlighting a commitment to sustainable development, the local communities of Mamberamo Foja will play a central role in the management of the new National Park.

Read more about the extraordinary biodiversity and ecosystems of the new National Park in this Living Bird feature story on Foja mountains published in 2012.

An urgent conservation opportunity

New Guinea is home to one of the world’s three tropical “megaforests” (alongside the Amazon and Congo basins) and holds over half the intact forest left in the Indo-Pacific region. These forests host the world’s richest island flora and many animal species, like the renowned birds-of-paradise, found nowhere else. New Guinea’s intact forests provide crucial benefits to people worldwide and offer nature-based solutions to environmental and societal challenges.

The forests are under threat from industrial-scale infrastructure development, commercial timber extraction, and permanent conversion for pulpwood and palm oil. International efforts to protect forests have overlooked intact regions, like Indonesian New Guinea (known as Papua), in favor of restoring regions with high deforestation rates. Protecting existing intact forests is inherently more cost-effective than restoring degraded ones. Conservation Media’s Papua Forest initiative aims to protect the homelands of the birds-of-paradise by helping partners keep Papua’s forests intact for the wildlife and people who depend on them.

Our partner-driven work is currently focused on three main goals:

- Increasing regional and global understanding of Papua’s forests, biodiversity, and cultures to help secure their future.

- Supporting efforts to establish large-scale conservation areas that promote sustainable development for the wellbeing of Papua’s indigenous peoples and local communities.

- Building and supporting partnerships to enhance conservation capacity.

In the beginning: The Birds-of-Paradise

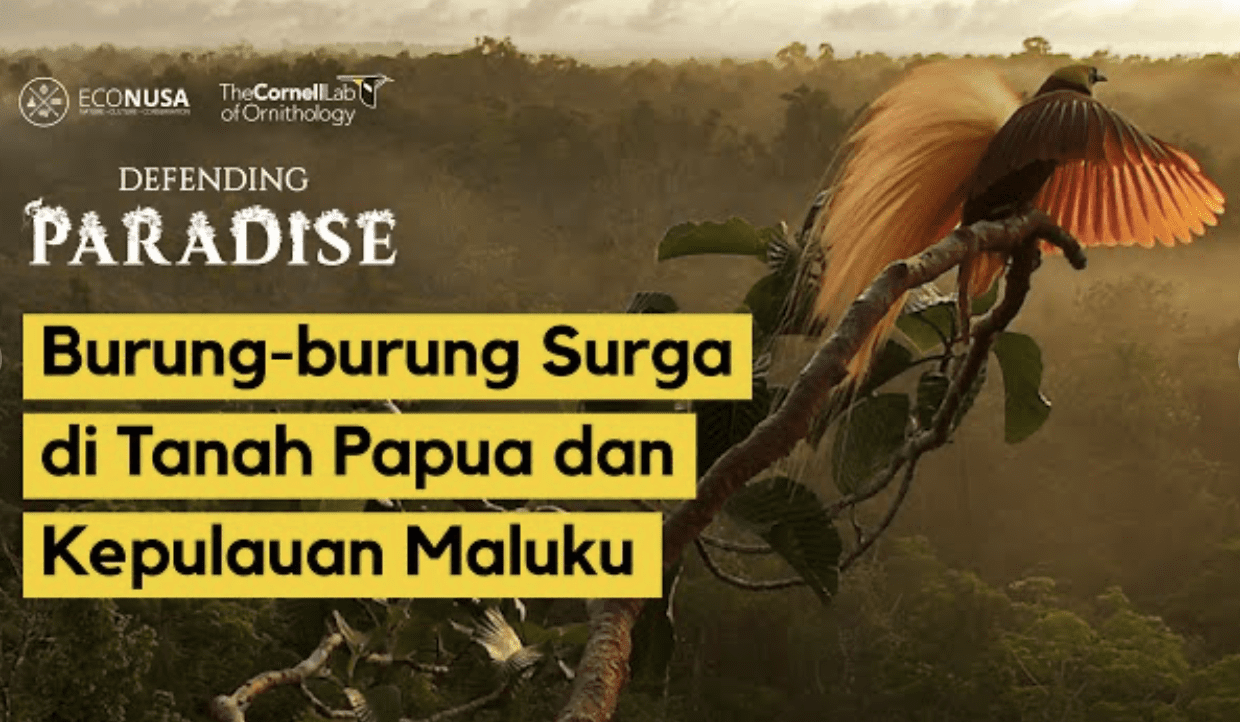

The birds-of-paradise are a family of birds that live only in New Guinea, a few surrounding islands, and a small part of eastern Australia. The 40+ species in the family are renowned for the brilliant colors and complex displays of the males – the result of sexual selection by females. In 2009, the Cornell Lab launched its Birds-of-Paradise Project, a monumental effort to document all the species in the wild for the first time. Through films, public lectures, museum exhibits and various forms of print and digital media, the Birds-of-Paradise Project has informed and inspired hundreds of million people worldwide about a special part of the natural world.

Protecting the homes of the birds-of-paradise

In 2018 the governments of Indonesia’s Papua provinces committed to protecting 70% of their forests. Conservation Media realized the footage it had collected provided an opportunity to help serve this initiative. Our science, films, and photography of the birds-of-paradise were shown at an international conference in Papua, focused on biodiversity and sustainable development, to raise awareness of this ambitious and important effort.

“Kids, now we’re in our forest. Why are we here? I want you to know what we have in front of us”

Indonesia’s Land of Papua – “Tanah Papua.”

Consisting of two provinces, Papua supports one of the only remaining large tropical forests in the world.

With the Amazon and Congo basins, these forests serve as the lungs of the planet. And in Papua, they are the lifeblood of the people.

“What impresses me the most about the forests of Papua is that they nurture/sustain the communities here. All resources needed to live, are found here.”

Papua’s geography contains a variety of ecosystems –

coasts, mangroves, forests…and mountains –

that supports roughly half of Indonesia’s biodiversity.

Over 600 species of birds are found in Papua, including the birds-of-paradise, many of which live nowhere else on earth.

“For me, the birds in Papua, especially the birds-of-paradise, are incredibly beautiful, unique, and unforgettable.”

The birds-of-paradise are icons of Papua’s biodiversity.

Their unparalleled beauty has made them a symbol of international renown.

“That’s a bird that tourists like to look for near the village.”

“Usually, we walk in the morning and listen. Then we follow the calls, and look for them.”

Global interest in Papua’s birdlife is leading to increased opportunity for wildlife tourism…bringing newfound economic benefits to local communities.

“… King of Cockatoo, White Cockatoo, Hornbill …”

“We can find the Magnificent playing on the ground. Then as we walk, we find Parotia. This is where they dance.”

“The bird we’re looking for tonight is Papuan frog mouth.”

“The forest gives us our water to drink, our food, it gives us our medicines, and provides the air we breathe.”

But these forests are no longer isolated from the rest of the world.

The demand for timber, palm oil, minerals and gas has arrived.

The future existence of Papua’s resources and biodiversity, and the communities that rely on them, depend on the choices made today.

The governments of Papua and West Papua are bringing together non-government, community, academic, and religious partners to create a sustainable pathway for development.

“Kids, don’t cut down this tree. Don’t do any harm. The trees are food for the birds, and the birds are the source of our income.”

There are plenty of examples of ecosystems destroyed by overexploitation. With its forests still intact, Papua has the opportunity to develop in a way that allows both its people and its environment to thrive.

“The beauty of Raja Ampat is beyond amazing.”

Recent successes in the marine environments of the Raja Ampat region of West Papua show that development and conservation can go hand in hand.

Within the forests, local leaders are organizing their communities with similar goals.

“Here are three useful and important things that matter to us: The first is the forest, the second one is conservation, and the last is tourism.”

“What’s important is that we take good care of the birds. The tourists see them and the money goes to the village.”

The forests, the birds, and the communities make this region unique…and irreplaceable.

“If the forests in Papua are destroyed, they’ve got nothing left. Their wealth and life resources are in the forest.”

As the lungs of the planet, tropical forests are an important buffer against our changing climate.

If Papua’s ecosystems are degraded, the effects will be felt not just locally, but across the world.

“The Arfak forest is very valuable and it’s critical for our future.”

Through collaborative leadership, achieving sustainable growth, maintaining the livelihood of local communities, and protecting globally significant biodiversity are possible…for Tanah Papua and all of humanity.

“Papuan nature is so beautiful. I ask Papuans all over: let’s protect our beautiful country so that our grandchildren will enjoy what we have today. Let’s support conservation in Papua.”

End of Transcript

Since 2015, there has been growing awareness to take a sustainable development approach in West Papua. We encourage non-deforestation commodities and ecotourism as an economic driver while considering the protection of the existing biodiversity.

Prof. Charlie Heatubun, West Papua Regional Research and Development Agency

The third largest rainforest in the world

In addition to raising awareness about local conservation efforts, Conservation Media has also focused on the global importance of this area. Papua hosts the third largest intact rainforest in the world after the Amazon and Congo basins but has almost none of the recognition of the other two, despite yielding equivalent benefits to people. This film was made in 2020 to show that protecting the forests of Papua and the surrounding Indo-Pacific is essential for building more resilient and prosperous societies for today and for the future.

[animal sounds]

[dramatic music]

[city sounds]

The Indo-Pacific. A region of diverse landscapes, wildlife, and cultures.

Its natural resources, including one of the world’s three major rainforests, have helped to create some of today’s fastest growing economies.

It is also home to a tenth of the world’s remaining intact tropical forests.

[animal sounds]

Intact forest are more than just tree-covered landscapes.

They are complex networks of living and non-living elements, with few signs of human activity, that are large enough to sustain entire ecosystem functions.

[monkeys howling]

They improve food security and water availability while protecting people from natural disasters and climate change.

And as the world confronts the health, social, and economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Indo-Pacific’s intact forests will play a key role in creating more resilient societies.

Maintaining the forests’ integrity will improve human wellbeing and support the natural systems we depend on.

And yet, their trajectory has been in decline for decades.

Twenty years ago, the Indo-Pacific was home to the second largest expanse of undisturbed rainforest in the world.

It covered roughly 188 million hectares, an area about twice the size of the island of New Guinea.

But it was losing forest more quickly than anywhere else.

Satellite records show that by 2019, this forest had been reduced to less than half of what it had been in 2001 with most cleared for resource extraction and infrastructure expansion.

In the northwest, the main drivers have been forestry, shifting small farms, and large-scale commercial agriculture.

In the central region, the leading factor was clear-cutting for palm oil production.

And in the east, losses came from shifting small farms and palm oil plantations.

Today with forests fragmented and degraded, few are large enough, and intact enough, to sustain all ecosystem functions while providing the full range of benefits that people depend on.

The intact forests that remain are essential.

[rainforest sounds]

About 30% are scattered widely, but roughly 70% are concentrated just within the islands of

Borneo and new Guinea, with around half, about 30 million hectares, in the New Guinea region alone.

[bird sounds]

These forest systems provide many undervalued benefits that are easy to overlook.

They support the highest levels of terrestrial biodiversity.

Up to 25,000 species of trees provide habitat and food for millions of forest-dependent plants, animals, fungi, and microbes.

Together their interconnected networks provide services that societies depend on, like nutrient cycling, seed dispersal, pollination, and pest resistance.

All for free.

[thunder crackling]

Beyond supporting biodiversity, intact forest systems also influence cloud cover and rainfall.

[thunder crackling]

They redistribute runoff, stabilize water tables, and regulate movement of nutrients and sediments, helping to maintain soil fertility for food production and preventing erosion.

And with today’s climate extremes, intact forests buffer people from the increasing intensity and frequency of heat waves, droughts, and floods.

These forests have also provided material and spiritual resources for forest-dependent communities for over 50,000 years.

And today, over 100 million people, roughly one quarter of the indigenous peoples worldwide, rely on their direct use for food, water, shelter, and livelihoods.

Forests provide benefits to human health by decreasing the negative impacts of smoke and haze by being better able to withstand wildfires than disturbed forests.

They yield compounds that supply millions of people with medicines worldwide.

Intact forests also reduce contact between humans and disease vectors, preventing the transmission of established and emerging infectious diseases that can impact human health and economic stability at global scales.

[rainforest sounds]

The benefits of intact forests also reach worldwide.

They provide a free service for mitigating the impacts of global climate change by storing carbon in their trees, soils, and peatlands.

The Indo-Pacific is estimated to hold up to 140 billion tons of carbon, with more than 40 billion tons in tree biomass alone.

Keeping them intact will play a vital role in preventing global warming from exceeding 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2030.

[airplane whirring]

The benefits of intact forests are increasingly clear.

Yet current land use plans are often at odds with maintaining their integrity.

For example, as of 2020, land concessions have been issued for much of the western half of New Guinea.

Millions of hectares have been allocated for industrial logging and wood pulp production, mining operations, and oil palm plantations.

Major infrastructure projects, including a 4,000-kilometer-long road network, are under way to facilitate these land use plans.

Throughout the Indo-Pacific, many intact forests face similar pressures.

[upbeat music]

If human health, indigenous cultures, food security, and low-cost tools for fighting climate change are to be provided by intact natural systems, then the current trajectory of use needs to be reconsidered.

Once intact forests are degraded, their benefits are lost for generations.

No known alternatives can restore all the services they provide.

[rainforest sounds]

Societies around the globe have exploited nature to shape the world we live in without recognizing the full value of intact natural systems.

This relationship has fueled development for centuries, but it is not sustainable for achieving economic growth while also reducing carbon emissions and ensuring human wellbeing.

Only by safeguarding these natural systems can we continue to draw on the environmental, economic, and human benefits they provide.

[bird noise]

For the forest-rich regions of the Indo-Pacific, protecting intact forests is a low-cost pathway for building more resilient and prosperous societies for today and for the future.

[rainforest sounds fade]

[animal sounds]

[dramatic music]

[city sounds]

The Indo-Pacific. A region of diverse landscapes, wildlife, and cultures.

Its natural resources, including one of the world’s three major rainforests, have helped to create some of today’s fastest growing economies.

It is also home to a tenth of the world’s remaining intact tropical forests.

[animal sounds]

Intact forest are more than just tree-covered landscapes.

They are complex networks of living and non-living elements, with few signs of human activity, that are large enough to sustain entire ecosystem functions.

[monkeys howling]

They improve food security and water availability while protecting people from natural disasters and climate change.

And as the world confronts the health, social, and economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Indo-Pacific’s intact forests will play a key role in creating more resilient societies.

Maintaining the forests’ integrity will improve human wellbeing and support the natural systems we depend on.

And yet, their trajectory has been in decline for decades.

Twenty years ago, the Indo-Pacific was home to the second largest expanse of undisturbed rainforest in the world.

It covered roughly 188 million hectares, an area about twice the size of the island of New Guinea.

But it was losing forest more quickly than anywhere else.

Satellite records show that by 2019, this forest had been reduced to less than half of what it had been in 2001 with most cleared for resource extraction and infrastructure expansion.

In the northwest, the main drivers have been forestry, shifting small farms, and large-scale commercial agriculture.

In the central region, the leading factor was clear-cutting for palm oil production.

And in the east, losses came from shifting small farms and palm oil plantations.

Today with forests fragmented and degraded, few are large enough, and intact enough, to sustain all ecosystem functions while providing the full range of benefits that people depend on.

The intact forests that remain are essential.

[rainforest sounds]

About 30% are scattered widely, but roughly 70% are concentrated just within the islands of

Borneo and new Guinea, with around half, about 30 million hectares, in the New Guinea region alone.

[bird sounds]

These forest systems provide many undervalued benefits that are easy to overlook.

They support the highest levels of terrestrial biodiversity.

Up to 25,000 species of trees provide habitat and food for millions of forest-dependent plants, animals, fungi, and microbes.

Together their interconnected networks provide services that societies depend on, like nutrient cycling, seed dispersal, pollination, and pest resistance.

All for free.

[thunder crackling]

Beyond supporting biodiversity, intact forest systems also influence cloud cover and rainfall.

[thunder crackling]

They redistribute runoff, stabilize water tables, and regulate movement of nutrients and sediments, helping to maintain soil fertility for food production and preventing erosion.

And with today’s climate extremes, intact forests buffer people from the increasing intensity and frequency of heat waves, droughts, and floods.

These forests have also provided material and spiritual resources for forest-dependent communities for over 50,000 years.

And today, over 100 million people, roughly one quarter of the indigenous peoples worldwide, rely on their direct use for food, water, shelter, and livelihoods.

Forests provide benefits to human health by decreasing the negative impacts of smoke and haze by being better able to withstand wildfires than disturbed forests.

They yield compounds that supply millions of people with medicines worldwide.

Intact forests also reduce contact between humans and disease vectors, preventing the transmission of established and emerging infectious diseases that can impact human health and economic stability at global scales.

[rainforest sounds]

The benefits of intact forests also reach worldwide.

They provide a free service for mitigating the impacts of global climate change by storing carbon in their trees, soils, and peatlands.

The Indo-Pacific is estimated to hold up to 140 billion tons of carbon, with more than 40 billion tons in tree biomass alone.

Keeping them intact will play a vital role in preventing global warming from exceeding 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2030.

[airplane whirring]

The benefits of intact forests are increasingly clear.

Yet current land use plans are often at odds with maintaining their integrity.

For example, as of 2020, land concessions have been issued for much of the western half of New Guinea.

Millions of hectares have been allocated for industrial logging and wood pulp production, mining operations, and oil palm plantations.

Major infrastructure projects, including a 4,000-kilometer-long road network, are under way to facilitate these land use plans.

Throughout the Indo-Pacific, many intact forests face similar pressures.

[upbeat music]

If human health, indigenous cultures, food security, and low-cost tools for fighting climate change are to be provided by intact natural systems, then the current trajectory of use needs to be reconsidered.

Once intact forests are degraded, their benefits are lost for generations.

No known alternatives can restore all the services they provide.

[rainforest sounds]

Societies around the globe have exploited nature to shape the world we live in without recognizing the full value of intact natural systems.

This relationship has fueled development for centuries, but it is not sustainable for achieving economic growth while also reducing carbon emissions and ensuring human wellbeing.

Only by safeguarding these natural systems can we continue to draw on the environmental, economic, and human benefits they provide.

[bird noise]

For the forest-rich regions of the Indo-Pacific, protecting intact forests is a low-cost pathway for building more resilient and prosperous societies for today and for the future.

[rainforest sounds fade]

End of Transcript

We call it paradise, because Papua and Maluku are like a piece of heaven that fell to earth, so we must protect it. Paradise is the forest and sea in Papua and Maluku that give us life, especially to the indigenous people of Papua and Maluku. It also serves as the biggest climate stabilizer currently in Indonesia and also the world, so it is an asset we should protect to sustain our lives in the long run.

Bustar Maitar, CEO of EcoNusa Foundation

Helping partners in Indonesia to defend their piece of paradise

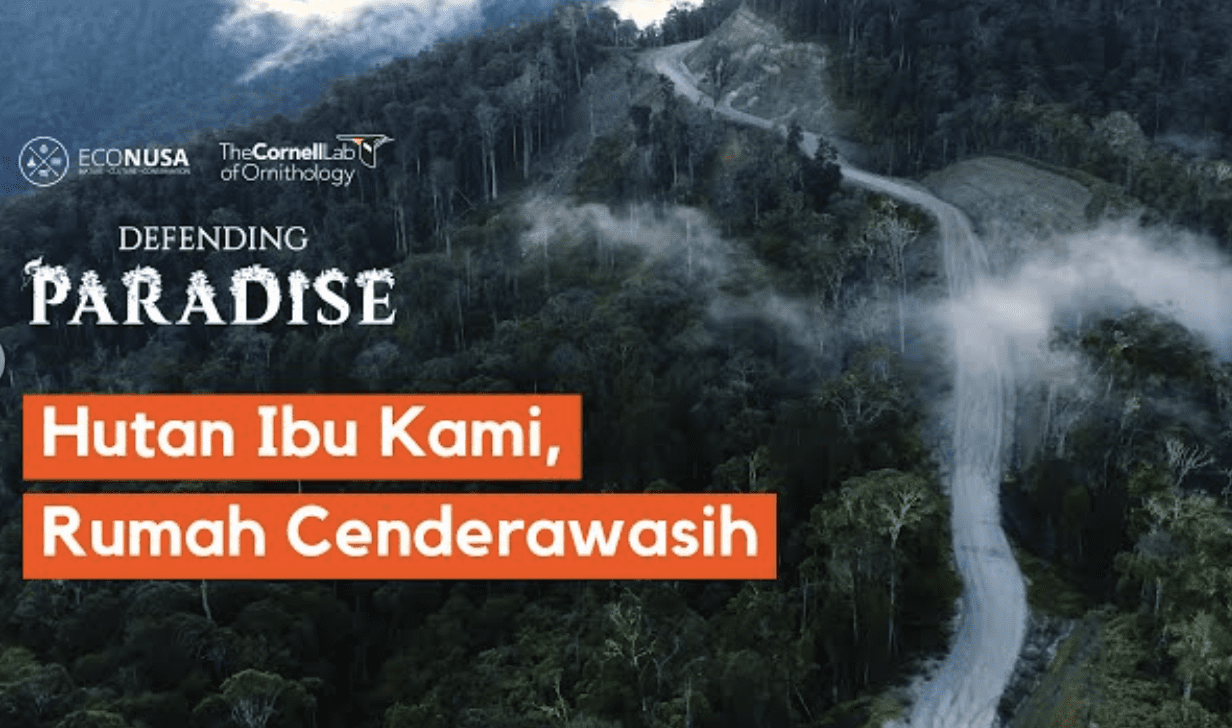

In 2021, Conservation Media partnered with the EcoNusa Foundation, an Indonesian non-profit dedicated to sustainable and equitable conservation practices in Papua, for the foundation’s “Defending Paradise” campaign spotlighting tropical rainforest preservation in eastern Indonesia. Conservation Media’s visual imagery was central to the campaign, which built appreciation among urban youth in Indonesia for a part of their country many regard as beautiful but also distant and unknown.

Protecting forests leads to better human health

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology produced two powerful videos helped make our events and online efforts stand out.

Dr. Nigel Sizer, Executive Director, Preventing Pandemics at the Source

In 2021, Conservation Media partnered with Preventing Pandemics at the Source, an organization focused on the links between the destruction of nature and increased pandemic risk, to create several films during the COVID-19 pandemic. These pieces highlight the root causes of zoonotic pandemics and how, by addressing those causes together, we can save lives, protect nature, and preserve the climate – all at once. The films helped provide context for several high-level events focused on One Health approaches during the 2021 UN General Assembly and the UN Climate COP26.

Our world as we know it is facing multiple existential threats. Greenhouse gas emissions are causing global warming and increasing the frequency and severity of floods, droughts, and heat waves. Habitat destruction, along with wildlife trade and consumption, are wiping out species essential to ecosystem resilience. On top of that scientists are warning us that deadly pandemics like Covid-19 will occur with increasing frequency.

Global leaders are struggling to address these three enormous and intertwined crises of climate change, biodiversity loss, and future pandemics. These are humanity’s most urgent challenges and yet we are overlooking a common solution that will help us solve all three at once – protecting our remaining intact forests. The world’s forests slow global warming by absorbing and storing carbon in their trees, soils, and peatlands. The carbon stored in today’s intact forests is equivalent to roughly 10 years worth of emissions caused by humans. Furthermore, intact forests absorb about one-fifth of the greenhouse gases that we emit annually. Keeping forests intact is essential to reaching the Paris agreement’s goal of preventing global warming from exceeding 1.5 degrees celsius by 2030. The vast majority of the world’s land-based species are found in forests. Species are often unable to subsist in the small fragments of forested land left behind after deforestation. Maintaining intact forests is therefore essential to avoid serious disturbances to the complex web of life.

Protecting forests will also help prevent the source of global pandemics –

the spillover of viruses from wild animals into humans. Nearly all global pandemics of the past century originated in wildlife. Most importantly, scientists overwhelmingly agree that animal-to-human spillover will be the most likely cause of the next pandemic. When people move into forested regions to clear land for agriculture and cattle rearing, to extract timber and minerals and to build roads and new frontier towns, they are increasing the probability of contact between humans and wild animals that may harbor new diseases. The risk is highest in tropical and subtropical areas where there is greater biodiversity. This can lead to the spillover of novel viruses, localized disease outbreaks, and potentially, the next global pandemic

It is clear that protecting remaining intact forests can mitigate the risk of three major crises – climate change, biodiversity loss, and emerging diseases. The good news is that effective and proven solutions to protect forests already exist – many of them spearheaded by local communities and indigenous peoples, who are the original guardians of these precious ecosystems. Our task now is to scale these solutions worldwide.

We can only do this by truly recognizing the value of these forests and mobilizing the money needed to enable governments, communities, and landowners to protect them. Forests are more than just tree-covered landscapes. They are complex networks of living and non-living elements, large enough to sustain entire ecosystem functions. If we fail to protect forests,

we do so at our own peril.

There is no backup plan – no alternative that can restore the many benefits that they provide. Forests are what stand between us and a future of unchecked climate change, biodiversity loss, and deadly pandemics. We must protect them for our planet, for our health, and for our children.

End of Transcript

A crucial turning point

In 2022, Conservation Media brought to life the research findings from a multi-national team of scientists who tracked deforestation over the last 20 years and predicted future risks to Papua’s remaining forests, especially risks posed by roads. While roads also provide access for sustainable development, they must be planned in coordination with sustainability goals to increase the wellbeing of the forests and the people of Papua. This film helped to build awareness about how a “business-as-usual” scenario will result in a six-fold increase in forest loss over the next 15 years.

[Music] in 2018 the governors of tana papua’s two provinces committed to a sustainable development path that would strengthen the prosperity and well-being of indigenous peoples and protect at least 70 percent of its forests [Music] tana papua’s forests are more than just tree-covered landscapes they’re complex networks of living and non-living elements that support plants animals and cultures found nowhere else they provide life-sustaining services like food security and water availability while protecting people from natural disasters and climate change

through these forests a massive road network is being built at nearly 4 000 kilometers long the trans-papua highway is part of a national plan to connect and serve the people of tana papua however the highway also increases the risk that papaw’s forests will be converted from intact to degraded ecosystems with negative impacts on local communities biodiversity and carbon emissions

studies show that the development that follows road expansion can lead to hot spots of deforestation for example the expansion of roads in sumatra and borneo over the last 20 years supported the loss of as much as 25 of forest habitat with most permanently converted to commercial agriculture like oil palm in tana papua only two percent of forests were cleared during that same time period but with the highway nearing completion that rate is likely to change

the trans-papua highway passes through some of indonesia’s most rugged landscapes from coasts to forests to its highest mountains

in 2009 kenya was a roadless village surrounded by forest along the pomats river satellite records show that road construction first reached the village from the south by 2013 it had crossed the river into lorenz national park a protected unesco world heritage site the road cut through the park’s fragile alpine ecosystems on its way to connect with towns in the north by 2020 another segment arriving from the east was nearly complete as the highway continues to expand so does the urban footprint of kenya and other villages along the route since 2000 in tana papua new roads and growing towns accounted for 15 of forest loss a total of more than 115 000 hectares [Music] during the same time period 120 000 hectares were cleared for industrial logging in the bomberai peninsula alone a dense logging network led to the loss of over 52 000 hectares

while many of these networks are temporary their scale is extensive and the vast uncut forests that remain within lands already slated for logging are at a high risk of degradation or loss

[Music] but the single greatest driver of permanent forest conversion during this 20-year period with industrial agriculture especially oil palm as seen in sumatra and borneo there is a clear correlation between road construction and the expansion of plantations today all of tana papua’s palm oil industry is located within 35 kilometers of the highway palm plantations account for 27 of total forest conversion

in 2010 roads built near the town of tamika paved the way for the construction of new plantations by 2014 plantations near the road were already extensive but without a bridge to improve access forest along the western front remained intact two years later with a bridge in place previously forested land had been almost completely converted to oil palm [Music] elsewhere the scale of conversion into industrial plantations is even larger southeastern papua is home to over 100 000 hectares of plantations including some of the biggest oil palm projects in indonesia with over a million hectares of forest licensed for future conversion to oil palm or pulpwood

tana papua’s forests and the future of its sustainable economy are at a turning point as of 2021 forest loss over the last 20 years has been limited but as seen in other parts of indonesia deforestation driven by unmanaged road development could be extensive if tana papua follows a similar path then it could experience a six-fold increase in forest loss over the next 15 years data-driven models accounting for factors like topography roads and existing concessions have identified areas at the highest risk of future loss together these deforestation hot spots are predicted to exceed 4.5 million hectares an area larger than switzerland this loss would undermine the commitment to protect tana papua’s unique biological and cultural heritage and it would come at a time when rates of tropical deforestation must not only be slowed worldwide but reversed to avert the worst impact of climate change

infrastructure initiatives like the trans-papua highway can benefit local communities by providing access to new development opportunities but the current path is rapidly opening tana papua to large-scale industrial projects at odds with international and local commitments to sustainable development and reversing forest laws

with careful coordination and planning roads and infrastructure can bring economic growth while advancing sustainability goals and increasing the well-being of the forests and the people of Tana Papua.

End of Transcript

Papua’s sustainable development efforts for intact rainforests presented at the UN Climate Conference

At the United Nations Climate Conference (COP28) in December 2023, Prof. Charlie Heatubun of the University of Papua and the West Papua government’s Research and Development Agency delivered a film and presentation about the Crown Jewel of Papua (CJP): the flagship sustainable development and conservation project in Indonesian New Guinea.

Prof. Charlie’s presentation was preceded by remarks from Razan al Mubarak, president of the International Union for Conservation of Nature and COP28’s UN Climate Change High-level Champion, who noted the critical role of the world’s three rainforest basins in nature-based solutions for both climate change and biodiversity protection. The presentation was the culmination of a multiyear effort by conservation groups to raise the profile of Papua’s intact forests, and the CJP in particular, on the international stage.

The film features the voices of the Indigenous and local communities safeguarding one of the world’s last great intact rainforests. Watch to experience how their values, knowledge, and partnership are critical to achieving global climate goals and shaping the future for all of us.

This film was made possible through the generous support of the Mastro Foundation.

The world’s largest tropical rainforests are in the Amazon, the Congo Basin and the Indo-Pacific.

Half of the remaining intact rainforest in the Indo-Pacific is within Indonesia, with most in Indonesian Papua.

Charlie Heatubun:

My first time going into the forest was when I was in 5th grade.

The temperature and atmosphere felt comfortable.

I heard birds singing and insect sounds. It was very calming.

Entering the forest felt like a different world.

Charlie Heatubun:

Indonesia is at the forefront of efforts to control climate change.

In recent years, we have succeeded in reducing emissions from the two main causes of deforestation and forest degradation.

Papua’s forests are very unique and serve essential functions for human life on planet earth because of their role in carbon sequestration, photosynthesis, and oxygen production.

And of course, these forests are closely connected to the culture and living needs of Indigenous People in Papua.

Muhammad Musa’ad:

I would like to convey to everyone, both in Indonesia and internationally, that in the middle of this vast world, there is still an island … the vast island of Papua, which today has 6 provinces, with biodiversity and fauna …. both on land and at sea.

Deasy Natalia Lontoh:

The leatherback turtles that lay eggs in Papua have a wide geographical range. Their feeding areas are in the Americas, the South China Sea, the central Pacific, Australia, and New Zealand.

Papua is home to many leatherback turtles, about 75% of their nesting activity is here.

Sebedius Siyoho:

Mangrove forests are important for local communities …mangroves protect crabs, fish, and other creatures like shellfish and snails.

Obaja Kalami:

There are parrots, there are cockatoos, there are birds of paradise, there are crowned pigeons…That’s what is unique here.

Benny Mambrasar:

So there are not just one or two bird-of-paradise species. There are 38 species in Papua.

Daniel Kalami:

For me, it’s very beautiful. The beauty first comes from their sounds, then the beauty continues with their feathers when they dance. – That’s what makes it beautiful.

Muhammad Musa’ad:

More than 80% of Papuan people live in interior areas, including remote areas of the forest. So nature becomes part of people’s lives.

Aldri Erwin Lagu:

For me, forests, seas, and land are very important.

The forest is like a mother, someone who gives me food and water.

The importance of the forest, land, and sea, they are everything to us.

Charlie Heatubun:

Currently, the most pressing global problem is related to climate change – especially global warming.

However, if we understand the local knowledge and culture of the people in Papua, we can avoid these things by following their way of life.

They take just enough natural resources to ensure that they can properly take care of their future needs.

Yanuarius Anouw:

The communities in Papua are always committed to protecting natural ecosystems.

Starting with the soil, they maintain the fertility of the land, and after that, the forest ecosystem.

Amos Kalami:

Take care of the forest, take care of the wood, sake care of the birds.

We have a commitment known as “Egek.”

“Egek” means we only take what is needed and let nature recover by itself.

Yunita Debi Ahoren:

As a woman, I believe that the forest is our life.

We don’t just live on the land; our life comes from the forest.

From the forest we can breathe, and we can move.

We’re powerless without the forest.

The forest is our life, and our life is the forest.

Benny Mambrasar:

We don’t want just us and our parents to enjoy nature, while future generations can’t experience it.

They would miss out on the beauty of nature.

We must be proud to have a country with extraordinary natural wealth.

As children of the nation, let’s take advantage of this opportunity to protect forests and nature.

Muhammad Musa’ad:

Papua in general has extraordinary potential…

and what is very important is the strong commitment of its people, especially indigenous communities and also regional governments, to be able to protect our environment, safeguard the wealth that God has bestowed on us.

For this reason, I invite all people in the world to contribute to protecting Papua for the future of the global community, not only Indonesia.

Charlie Heatubun:

There’s a saying that goes: “sustainable forests, prosperous communities.”

However, for us in West Papua, it’s the opposite: “prosperous communities, sustainable forests.”

We all live in the same country and on same planet. It’s important to know that what we do will affect the quality of life for people everywhere.

If Papuan communities are prosperous, forests are sustainable, our country will also be prosperous. This can be a good example for other countries, that we carry out the noble duties for the welfare of future generations.

The important thing is our unwavering commitment and motivation to collaborate. Big things cannot be achieved alone. The most important factor is our strong will to work together and move forward collectively.

End of Transcript

A presentation of the Government of the Republic of Indonesia, the Provincial Government of West Papua, and the Provincial Government of South-West Papua. Produced by the Cornell Lab and the Rekam Nusantara Foundation.

What’s next for the birds and the people

Indonesia holds the third largest area of rainforest in the world and is second in total biodiversity (after Brazil). This rich natural heritage makes Indonesia one of the most important international players for action on climate change and biodiversity protection. Between 2001-2021, Indonesia lost 18% (28.6 million hectares) of its total tree cover, emitted 19.7 Gt of carbon dioxide (equivalent). Encouragingly, Indonesia has seen a significant reduction in deforestation following a peak in 2016. With its 2030 Forestry and Other Land Use (FOLU) Net Sink plan, Indonesia has a pathway for achieving net zero carbon emissions in the forest and land use sectors by 2030.

…under the leadership of President Jokowi and Minister Siti Nurbaya, Indonesia’s efforts to reduce CO2 emissions from deforestation is one of the largest single climate mitigation contributions since we agreed on the Paris Agreement in 2015. Indonesia is truly an inspiration for…the whole world.

Ambassador Hans Brattskar, Norway Special Envoy on Climate and Forest Ambassador

A flagship effort in Indonesia’s western Papua provinces is the proposed “Crown Jewel of Papua” (CJP) sustainable development and conservation landscape. At roughly 2.5 million hectares, about half the size of Costa Rica, this landscape is a key step to ensuring the commitment of 70% of forests protected. This effort aims not only to be a vast protected area (possibly the largest in Southeast Asia), but to model how conservation and development can go hand-in-hand to improve the wellbeing of Papuans while also helping Indonesia achieve its national climate goals.

In coming years, Conservation Media will help partners establish the CJP landscape by providing a suite of media resources for national and international events. These resources will support stakeholders’ goals of showcasing the feasibility and impact of the CJP effort on human wellbeing and intact rainforest protection.

We are also proud to partner with the Indonesian-based Rekam Nusantara Foundation in this effort and in their production of a documentary miniseries for Indonesian national television. This project explores the relationship between nature, people, and culture in Papua, as Papuans face the impacts of climate change on their environmental, social, and cultural identities.

For us, our life is glorious because of the green. Our happiness and our life depend on nature. Our life depends on the forest. All animals, plants, and water are part of nature created by God. Therefore, all of the voices coming from nature are worshiping God. Because they are part of nature, birds-of-paradise voices sing for the greatness of God.

Ondoafi Gustaf Toto, Oldest Customary Leader in Necheibe Village, Papua