Updates and Corrections—October 2025

This document accompanies the eBird/Clements Checklist v2025 spreadsheet (tap or click link for downloads and recommended citation).

Note the following:

- Numbers preceding accounts are taxon order numbers specific to the 2025 eBird/Clements update. These differ from year to year but are used here to facilitate sequential treatment.

- WGAC (Working Group Avian Checklists of the IOU) is now referred to throughout as AviList. Nearly all decisions taken by AviList (AviList Core Team 2025) have been enacted in Clements et al. (2025).

- The IOC-WBL, also known simply as the IOC list, is the Gill and Donsker and Gill et al. checklists; the version referred to is always 15.1 unless specifically stated (but note that specific taxonomic decisions may have been implemented in earlier versions than 15.1).

- HBW and BirdLife International (2025). Handbook of the Birds of the World and BirdLife International digital checklist of the birds of the world. Version 10.

- NACC checklist

- SACC checklist

Species Gains and Losses

Splits

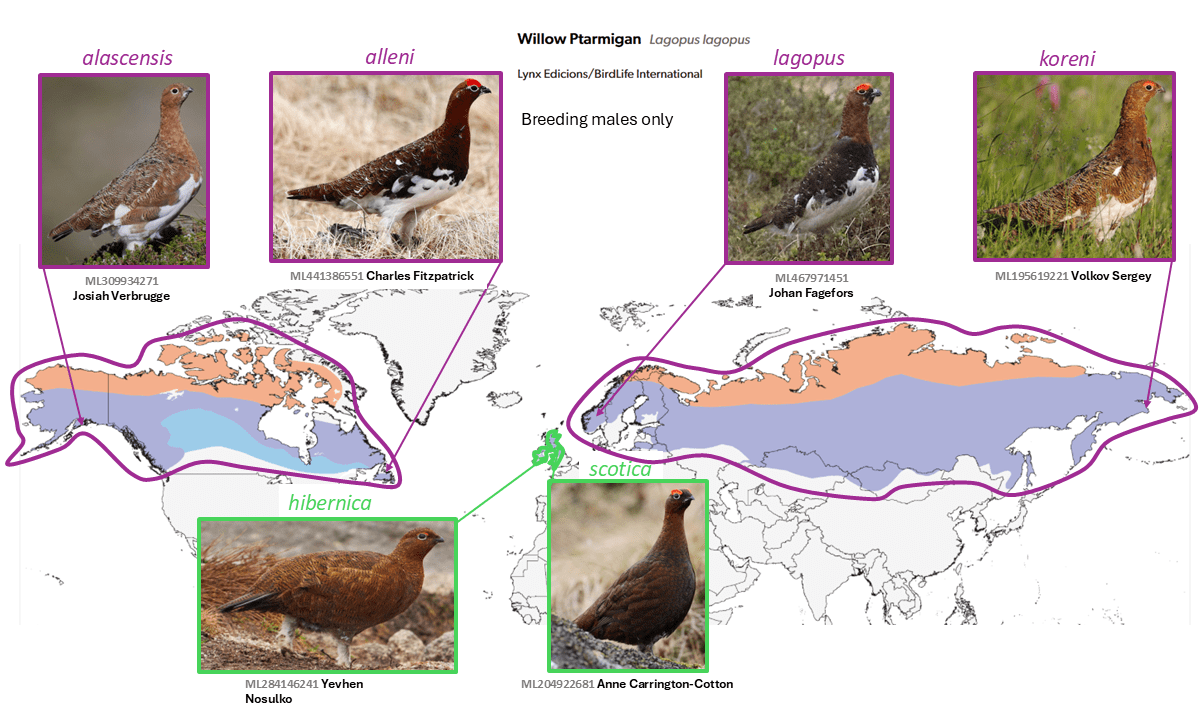

Red Grouse Lagopus scotica is split from Willow Ptarmigan Lagopus lagopus

Summary: (1→2 species) The Red Grouse, endemic to the British Isles, differs from all other taxa of Willow Ptarmigan in its molts and plumages, and forms a distinct genetic group.

Details: v2025 taxa 1351–1372

Was:

- Willow Ptarmigan Lagopus lagopus

- subspecies: variegata, lagopus, rossica, birulai, koreni, kamtschatkensis, maior, brevirostris, kozlowae, sserebrowsky, okadai, muriei, alexandrae, alascensis, leucoptera, alba, ungavus, alleni, hibernica, and scotica

Now:

- Red Grouse Lagopus scotica

- subspecies: hibernica and scotica

- Willow Ptarmigan Lagopus lagopus

subspecies: variegata, lagopus, rossica, birulai, koreni, kamtschatkensis, maior, brevirostris, kozlowae, sserebrowsky, okadai, muriei, alexandrae, alascensis, leucoptera, alba, ungavus, and alleni

Graphical abstract:

Long treated as members of the highly polytypic Holarctic Willow Ptarmigan Lagopus lagopus (Linnaeus, 1758), the two (or one, depending on taxonomy adopted) taxa in the British Isles, scotica (Latham, 1787) and hibernica (Kleinschmidt, 1919), are the only ones with wholly dark wings and no molt into a white winter plumage. Despite their very wide distribution, including on islands, all the other subspecies are fairly similar in plumage and molts. In fact, even Peters (1934) treated scotica and hibernica as separate species. While these morphological aspects were long argued to be of only subspecific importance (as treated by e.g. Wolters 1976), genomic data show that scotica and hibernica form a monophyletic, fairly well-diverged clade (Quintela et al. 2010, Kozma et al. 2019, Sangster et al. 2022). Nevertheless, they appear to be similar vocally to taxa of Lagopus lagopus, although a vocal analysis should be carried out. On balance, the evidence is deemed by AviList Core Team (2025) and NACC (Chesser 2025, 2025-B-10; Chesser et al. 2025) to support specific status for Lagopus scotica, while the recognition of subspecies hibernica requires further study, as it is currently recognized by eBird/Clements (v2025) but not by AviList Core Team (2025).

English names: The English name Red Grouse has been very widely used and is thus deeply entrenched, and thus no change is made in that respect. The Willow Ptarmigan sensu stricto has a Holarctic distribution, so its much larger range and the wide familiarity of the English name means that no change is required.

Mexican Squirrel-Cuckoo Piaya mexicana is split from Squirrel Cuckoo Piaya cayana

Summary: (1→2 species) Western Mexico gains another endemic species with the split of the Mexican Squirrel-Cuckoo, which differs somewhat both in vocalizations and plumage from Common Squirrel-Cuckoo.

Details: v2025 taxa 3217–3232

Was:

- Squirrel Cuckoo Piaya cayana

- subspecies: mexicana, thermophila, nigricrissa, mehleri, mesura, circe, cayana, insulana, obscura, hellmayri, pallescens, cabanisi, macroura, and mogenseni

Now:

- Mexican Squirrel-Cuckoo Piaya mexicana (monotypic)

- Common Squirrel-Cuckoo Piaya cayana

Subspecies: thermophila, nigricrissa, mehleri, mesura, circe, cayana, insulana, obscura, hellmayri, pallescens, cabanisi, macroura, and mogenseni

Graphical abstract:

The West Mexican squirrel cuckoo taxon mexicana (Swainson, 1827) was long treated as a subspecies of the widespread, polytypic Neotropical Piaya cayana (Linnaeus, 1766), including by Peters (1940) and Wolters (1976), but it was split based on morphological differences by del Hoyo and Collar (2014). A recent study (Sánchez-González et al. 2023) showed limited evidence of introgression in a region of parapatry between mexicana and thermophila Sclater, 1860 in southeastern Mexico, and that mexicana forms a monophyletic clade, although it is less deeply diverged from the Middle and northern South American taxa than is the Amazonian cayana clade (Smith et al. 2014). However, several vocal differences exist between mexicana and all other taxa (Dyer and Howell 2023, Johnson et al. 2025, 2025-C-14a,b), while the other taxa seem to be more similar to each other vocally.

There is a nomenclatural issue regarding whether the name circe Bonaparte, 1850 or mehleri Bonaparte, 1850 has priority for the Middle and northern South American taxa. Pending resolution of this issue, AviList Core Team (2025) and Chesser et al. (2025) voted to split only mexicana from the remainder at this time. The taxa with greenish eye-rings (thermophila, nigricrissa, circe, and insulana) of Middle and northern South America should probably be united in one group, while the remaining taxa, which have red eye-rings and occur in Amazonia and southward, should likely be separated in the cayana group. Based on apparent parapatry and genetics (Johnson et al. 2025), these are likely to be considered separate species in the future.

English names: The English name Mexican Squirrel-Cuckoo has been adopted for the newly split mexicana, with Common Squirrel-Cuckoo for Piaya cayana s.s. (as used by del Hoyo and Collar 2014 and Chesser et al. 2025). The usage of hyphens denotes that these are considered to form a monophyletic group.

Hudsonian Whimbrel Numenius hudsonicus and Eurasian Whimbrel Numenius phaeopus are split from Whimbrel Numenius phaeopus

Summary: (1→2 species) The Hudsonian and Eurasian whimbrels, the former breeding patchily in Nearctic tundra and the latter patchily in Palearctic tundra and steppe, have similar vocalizations but differ strongly in rump color and are deeply diverged genetically.

Details: v2025 taxa 6011–6017

Was:

- Whimbrel Numenius phaeopus

- subspecies: phaeopus, alboaxillaris, rogachevae, variegatus, and hudsonicus

Now:

- Eurasian Whimbrel Numenius phaeopus

- subspecies: phaeopus, alboaxillaris, rogachevae, and variegatus

Hudsonian Whimbrel Numenius hudsonicus (monotypic)

Graphical abstract:

Since about 1934 (Peters 1934), the North American-breeding taxon hudsonicus Latham, 1790 of whimbrel has been considered a subspecies of a circumpolar Whimbrel Numenius phaeopus (Linnaeus, 1758). This treatment was adopted by the AOS in 1944 (AOS 1944), and subsequently most authorities have considered them conspecific. The most obvious phenotypic difference between hudsonicus and the Old World taxa comprising phaeopus is the dark rump of the former vs. the white rump of the latter, which has generally been considered an insufficient basis to justify species status. Indeed, one subspecies of Old World phaeopus, the steppe-breeding alboaxillaris Lowe, 1921 is arguably equally distinct to hudsonicus phenotypically, with its white underwing linings, vs. these being heavily barred in other taxa including hudsonicus. In addition, vocalizations of all appear similar, unlike those of most other shorebird species pairs, although a formal vocal analysis may show some differences.

However, mtDNA and genomic data (Zink et al. 1995, Humphries and Winker 2011, Tan et al. 2019, McLaughlin et al. 2020) have shown that hudsonicus is deeply diverged relative to the Old World taxa, and thus has evidently been reproductively isolated from them for a considerable period. Although their breeding grounds are far apart, these are very long-distance migrants and both the eastern variegatus/rogachevae group of phaeopus and hudsonicus regularly appear in western Alaska (Gibson and Withrow 2015). Although a fairly recent proposal to NACC (Winker 2022, 2022-A-10) did not pass, the deep divergence and evidence for reproductive isolation led AviList Core Team (2025) to consider hudsonicus a separate species.

English names: The English names Hudsonian Whimbrel for Numenius hudsonicus and Eurasian Whimbrel for Numenius phaeopus have previously been widely adopted for this species pair (summarized in Winker 2022), and are therefore used here.

Atlantic White-Tern Gygis alba, Blue-billed White-Tern Gygis candida, and Little White-Tern Gygis microrhyncha are split from White Tern Gygis alba

Summary: (1→3 species) The beautiful white-terns of tropical seas differ from each other in bill shape and color, and in size, among other ways, and now are treated as three distinct species, one in the Atlantic, one in the Indian and Pacific oceans, and one now only in the Marquesas of the tropical Pacific.

Details: v2025 taxa 6626–6630

Was:

- White Tern Gygis alba

- subspecies: alba, candida, leucopes, and microrhyncha

Now:

- Atlantic White-Tern Gygis alba (monotypic)

- Blue-billed White-Tern Gygis candida

- subspecies: candida and leucopes

Little White-Tern Gygis microrhyncha (monotypic)

Graphical abstract:

Although each was originally described as a full species, Gygis alba (Sparrman, 1786) of the tropical Atlantic, candida (Gmelin, 1789) (including leucopes Holyoak & Thibault, 1976) of the tropical Indo-Pacific, and microrhyncha Saunders, 1876 of the eastern tropical Pacific have long been considered conspecific, including by Peters (1934). However, their differences in morphology defy application of criteria typical of subspecies, especially their bill morphology and coloration, but also size and differences in wing and tail shape (Olson 2005, Pratt 2020). Furthermore, there are evidently vocal differences (Pratt 2020), and prehistoric sympatry between candida and microrhyncha over a wide area (Steadman 2006). However, the range of microrhyncha has now contracted markedly, and it apparently hybridizes with candida in part of its now-limited range (Pratt 2020). In addition, mtDNA data show only limited genetic divergence, which may be due to introgression (Yeung et al. 2009, Thibault and Cibois 2017).

Based mainly on the marked morphological differences and past sympatry (Pratt 2025a, b), a three-way split was agreed upon by AviList Core Team (2025), NACC (Pratt 2024, 2025-A-3a, b; Chesser et al. 2025), and SACC (Remsen et al. 2025).

English names: We follow the English names adopted by AviList Core Team (2025), NACC (2025-D-1; Chesser et al. 2025), and SACC: Atlantic White-Tern Gygis alba; Blue-billed White-Tern Gygis candida; and Little White-Tern Gygis microrhyncha. Suggestions that involve some version of “Fairy” in the group name were not adopted due to the potential for confusion with Sternula nereis, which throughout much of its range (Australia to New Caledonia) has long been known as “Fairy Tern”, although in eBird/Clements (v2025 and prior versions) and AviList Core Team (2025) the name “Australian Fairy Tern” is used. The group name “White Tern” has long usage and is adequate, and is here hyphenated to indicate that it forms a monophyletic group.

Western Rockhopper Penguin Eudyptes chrysocome and Eastern Rockhopper Penguin Eudyptes filholi are split from Southern Rockhopper Penguin Eudyptes chrysocome

Summary: (1→2 species) The rockhopper penguins of the southern South American region differ from those of southern Indian and southwestern Pacific ocean islands in DNA, and subtly in morphology.

Details: v2025 taxa 6965–6966

Was:

- Southern Rockhopper Penguin Eudyptes chrysocome

- subspecies: chrysocome and filholi

Now:

- Western Rockhopper Penguin Eudyptes chrysocome

- Eastern Rockhopper Penguin Eudyptes filholi

Graphical abstract:

The subantarctic rockhopper penguins were long considered a single species, Eudyptes chrysocome (Forster, 1781), as in Peters (1931) and Wolters (1975). Since then, the populations breeding on temperate-latitude islands in the South Atlantic and South Indian oceans, moseleyi Mathews & Iredale, 1921, despite its relatively late description and despite having considered a synonym by some (including Peters 1931 and Wolters 1975), have been shown to be highly distinct in numerous ways, including morphology, genetics, vocalizations, and breeding phenology, and this split has been broadly accepted. The taxonomic status of the southern-breeding populations, however, has been more controversial. It has long been known that the populations breeding in the southern South American region, chrysocome, differ from those breeding in the South Indian and Southwest Pacific oceans, filholi Hutton, 1879 in morphology, mainly the absence in the former and presence in the latter of a prominent pale pink border to the lower mandible and the gape, as well as a narrower bill, slightly different underwing markings, and typically a narrower yellow stripe above the eye, and indeed filholi and chrysocome were originally described as separate species. The bill border feature is remarkably consistent within populations, despite the major range disjunction between breeding colonies of filholi in the South Indian and Southwest Pacific oceans, and the lack of differentiation between the two latter highly disjunct populations.

Frugone et al. (2021) presented an integrative analysis that suggested negligible hybridization between filholi and chrysocome, and supported the elevation of filholi to species status. Vocalizations (which are incompletely known for filholi) appear to be similar but perhaps screechier and less nasal in filholi than chrysocome, although vocal differentiation (or its lack) between most species of Eudyptes remains to be elucidated. Morphological distinctions between two other species of Eudyptes (Fiordland Eudyptes pachyrhynchus Gray, 1845 and Snares Eudyptes robustus Oliver, 1953) are quite similar and equally modest, and the latter was only fairly recently described; nevertheless, these have long generally been considered separate species. Taking all the above into consideration, AviList Core Team (2025) voted to consider filholi a separate species. SACC, however, recently voted not to split these based on their apparent similarity in vocalizations, shallow genetic divergence, and unclear significance to interbreeding of the main morphological difference, the pale pink skin bordering the lower edge of the mandible and gape in filholi that is lacking in chrysocome.

English names: When split, the English name Southern Rockhopper Penguin is no longer useful, clear, or apt for either of the component species since chrysocome and filholi occur at approximately equal latitudes. Nevertheless, Southern Rockhopper Penguin has been widely used for chrysocome and Eastern for filholi (e.g., Howell and Zufelt 2019, Frugone et al. 2021, Harrison et al. 2021). Because both occur in multiple island groups, and to contrast with Eastern Rockhopper Penguin, already widely familiar for filholi, the name Western Rockhopper Penguin has been adopted here.

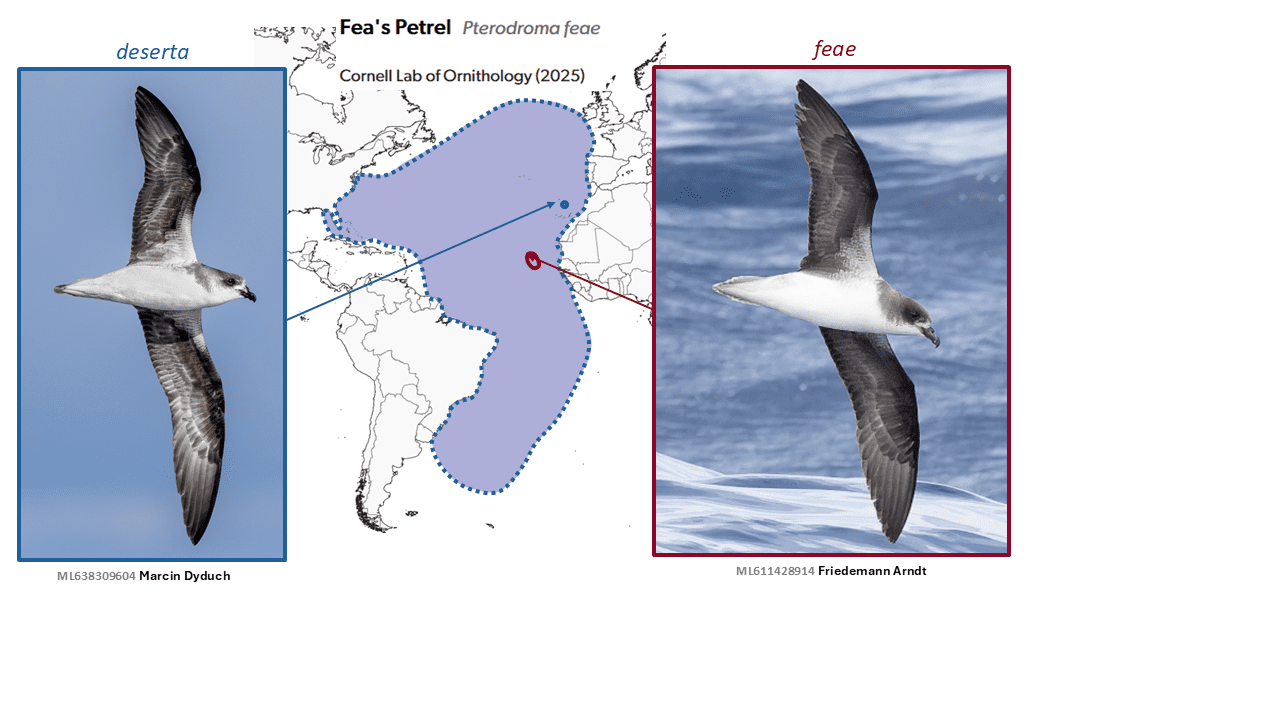

Cape Verde Petrel Pterodroma feae and Desertas Petrel Pterodroma deserta are split from Fea’s Petrel Pterodroma feae

Summary: (1→2 species) Two petrels that breed only on the Atlantic islands, one on of Bugio in the Desertas and the other on Cape Verde, differ markedly in breeding biology and other aspects, despite their similar plumage.

Details: v2025 taxa 7119–7120

Was:

- Fea’s Petrel Pterodroma feae

- subspecies: feae and deserta

Now:

- Cape Verde Petrel Pterodroma feae (monotypic)

- Desertas Petrel Pterodroma deserta (monotypic)

Graphical abstract:

Map notes: The non-breeding range of feae sensu stricto is poorly known, but most individuals appear to remain near the breeding colonies all year, while deserta has a far more extensive non-breeding range (indicated by dashed blue line).

The taxonomy of the Pterodroma mollis (Gould, 1844) complex has seen major change through the years, with Peters (1931) considering it to comprise two subspecies, the subantarctic mollis and feae (Salvadori, 1899), the latter taxon breeding on Madeira and the Cape Verdes. Soon afterward, two further taxa were described, deserta Mathews, 1934, with type locality Desertas Islands, and madeira Mathews, 1934, with type locality Madeira, leaving feae restricted to Cape Verde. Mathews (1934a, b) described both deserta and madeira as subspecies of mollis, and also considered feae to be a subspecies of mollis.

Numerous authors have proposed splitting the mollis complex, in various ways (summarized in Jesus et al. 2009). For example, Wolters (1975) treated madeira as a distinct species, while considering feae a subspecies of mollis. Particularly influentially, on the basis of plumage, structure, and vocalizations, Bretagnolle (1995) suggested a two-way division into subantarctic mollis vs. the three Macaronesian taxa. This treatment held sway for years, and is further supported by molecular results suggesting mollis is not sister to the feae clade (Jesus et al. 2009). Zino et al. (2008) argued for the specific separation of deserta as well, and Jesus et al. (2009) provided further evidence in support of that treatment. The rationale for the split of deserta includes that it is a summer breeder, only on the single island of Bugio, in the Desertas Islands, part of Madeira, where it usually nests in burrows, while feae is a winter breeder in the Cape Verde Islands, usually occupying rock crevices. In addition, there are vocal differences between all three (The Sound Approach 2008). Furthermore, the at-sea distributions of deserta and feae apparently differ dramatically, with deserta ranging throughout the Atlantic, as demonstrated by geolocators (Ramírez et al. 2013, Howell and Zufelt 2019), while feae s.s. is evidently largely sedentary, with some reaching waters off Senegal (Militão et al. 2025), although its at-sea range is still unclear. Morphological differences, such as in bill morphology, are however rather slight, and field identification is problematic.

The major difference in breeding season surely forms a temporal barrier to interbreeding, much as in the case of giant-petrels and some storm-petrels. Coupled with the other differences, the specific status of deserta was agreed upon by AviList Core Team (2025).

English names: Given fairly similar-sized breeding ranges of the two daughter species (though evidently not of non-breeding ranges) and the potential for confusion due to the fact that the name Fea’s Petrel has been very widely used to refer to what is now known to be deserta rather than feae, the use of the name Fea’s Petrel is discontinued here. The geographically clarifying names Cape Verde Petrel and Desertas Petrel are adopted for their breeding ranges (as in e.g. Howell and Zufelt 2019). Bugio Petrel, used by Ramírez et al. (2013), is also an apt name for deserta and highlights the importance of its sole breeding island, although it introduces yet another term for this already-confusing complex that does not mirror the specific epithet.

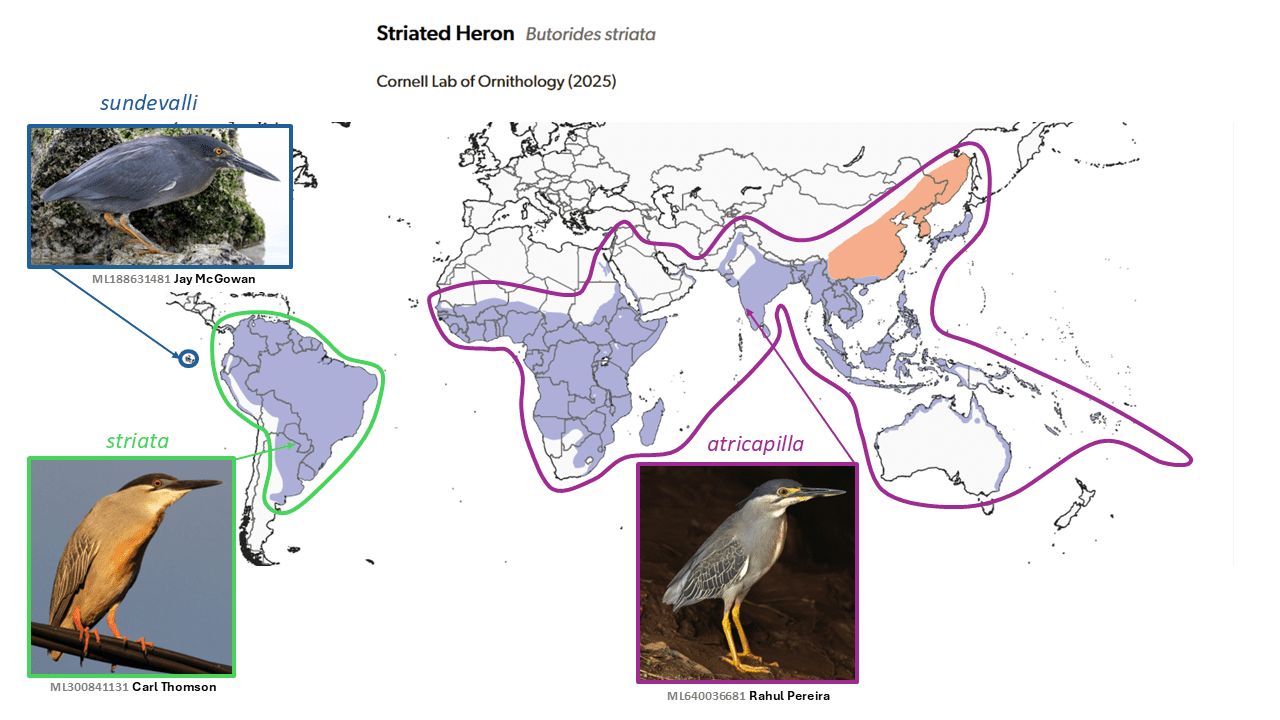

Little Heron Butorides atricapilla and Lava Heron Butorides sundevalli are split from Striated Heron Butorides striata

Summary: (1→3 species) The usually blackish-gray Lava Heron of the Galapagos and the mainly South American Striated Heron, with its distinctive rufous stripe on neck sides, are split from the widely distributed and highly variable Little Heron of the Old World tropics and subtropics, which lacks the rufous-bordered neck stripe, among other differences.

Details: v2025 taxa 7669–7703

Was:

- Striated Heron Butorides striata

- subspecies striata, sundevalli, atricapilla, brevipes, crawfordi, rhizophorae, rutenbergi, degens, didii, albidula, albolimbata, amurensis, actophila, javanica, spodiogaster, carcinophila, steini, moluccarum, papuensis, littleri, idenburgi, flyensis, rogersi, cinerea, stagnatilis, macrorhyncha, solomonensis, and patruelis

Now:

- Striated Heron Butorides striata (monotypic)

- Lava Heron Butorides sundevalli (monotypic)

- Little Heron Butorides atricapilla

- subspecies atricapilla, brevipes, crawfordi, rhizophorae, rutenbergi, degens, didii, albidula, albolimbata, amurensis, actophila, javanica, spodiogaster, carcinophila, steini, moluccarum, papuensis, littleri, idenburgi, flyensis, rogersi, cinerea, stagnatilis, macrorhyncha, solomonensis, and patruelis

Graphical abstract:

While the taxonomic status of the Lava Heron, Butorides sundevalli (Reichenow, 1877), of the Galapagos Islands has varied greatly, with many authorities treating it as a full species (including Peters 1931) and many others (including Wolters 1976) as a subspecies. In contrast, until very recently nearly all authors considered Butorides striata (Linnaeus, 1758) to be pantropical, with many subspecies. However, Peters (1931) also recognized rogersi Mathews, 1911 of northwestern Australia as a full species, as originally described, a treatment since shown to be untenable (as presaged by the comment by Peters that rogersi would likely prove to be a color-phase).

Mendales (2023) showed using genomic data that all New World Butorides taxa form a clade that is sister to that formed by all sampled Old World taxa, and therefore that the longstanding treatment is untenable. Given that Butorides virescens (Linnaeus, 1758) has long been considered a full species largely on the basis of apparent assortative mating (Hayes 2002, Hayes et al. 2013), a four-species treatment of the genus was adopted by AviList Core Team (2025), the most novel one being the split of mainly South American atricapilla (Afzelius, 1804), although this was originally described at the species level (long before the invention of subspecies). Further splits (for example a four-way split of Old World taxa into four species: African atricapilla, Arabian brevipes, Asian javanica, and Australasian macrorhyncha adopted by J. Boyd, among Old World taxa may prove to be justified, but sampling in Mendales (2023) was inadequate to resolve this issue.

Further work on the morphology and taxonomy of the group is in progress (Rasmussen ms). Butorides sundevalli, however, though usually blackish, is extraordinarily variable in plumage for a single taxon, especially one with a small range. The many subspecies of the atricapilla group together exhibit even greater plumage and size variation, including some dark morphs that strongly resemble sundevalli. The South American striata s.s., in contrast, is monotypic and is much less variable in plumage over its wide range, though a few individuals south to Argentina have a brownish-rufous rather than gray neck. See under Changes to Groups section for division of Old World taxa in Butorides atricapilla into groups.

Notably, in contrast to the other New World taxa, sundevalli is nearly restricted to rocky coastlines and adjacent mangroves (and has adapted to coastal human structures). Some Old World taxa (e.g. brevipes of the Persian Gulf region and the Australian taxa) are largely restricted to coastlines and mangroves, while most other taxa are typically found inland.

The specific status of Green Heron Butorides virescens is also open to question, and it has often been considered conspecific with its congeners (e.g. in Wolters 1976), but is treated as a full species by AOS, based partly on Hayes (2002) and Hayes et al. (2013).

English names: The previously used names Striated, Lava, and Little Herons are used for South American striata s.s., Galapagos sundevalli, and Old World atricapilla, respectively. However, further work is needed to establish more useful and less confusing names than Striated and Little Herons.

Coppery-tailed Trogon Trogon ambiguus is split from Elegant Trogon Trogon elegans

Summary: (1→2 species) Two trogons that are widely separated by the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in southern Mexico differ in plumage and somewhat in voice, and are now considered separate species.

Details: v2025 taxa 9569–9575

Was:

- Elegant Trogon Trogon elegans

- subspecies canescens, goldmani, ambiguus, elegans, and lubricus

Now:

- Coppery-tailed Trogon Trogon ambiguus

- subspecies canescens, goldmani, and ambiguus

- Elegant Trogon Trogon elegans

- subspecies elegans and lubricus

Graphical abstract:

Although lumped by nearly all authorities since Peters (1945), with the exception of Oberholser (1974), the broadly allopatric Mesoamerican Trogon ambiguus Gould, 1835, occurring in Mexico north of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec and marginally in the southwestern USA, and Trogon elegans Gould, 1834 groups of Central America south to northwestern Costa Rica were again treated as separate species by del Hoyo and Collar (2014). This split was based on plumage differences: adult males of the two forms differ in undertail pattern and uppertail color, as well as (more subtly) in wing covert vermiculation. Furthermore, they differ (with some overlap, and with no formal vocal analysis yet) in primary vocalizations, the song of ambiguus being typically delivered at a faster rate than that of elegans (Remsen 2022, NACC proposal set 2022-A).

Dyer and Howell (2023) treated the two as specifically distinct on the basis of plumage and voice. However, given that no comprehensive vocal analysis has been done, the apparent within-taxon variation in voice, rather minor mtDNA differentiation (DaCosta and Klicka 2008), and the known intergradation of other Trogon taxa with similar levels of plumage variation, the above NACC proposal did not pass. AviList Core Team (2025), however, considered that the balance of evidence favors the two-species treatment.

English names: The English names that have been fairly broadly adopted for the two daughter species are tentatively adopted. However, some degree of confusion is likely to result due to the retention of the name Elegant Trogon for the southern daughter species Trogon elegans, and further consideration is needed.

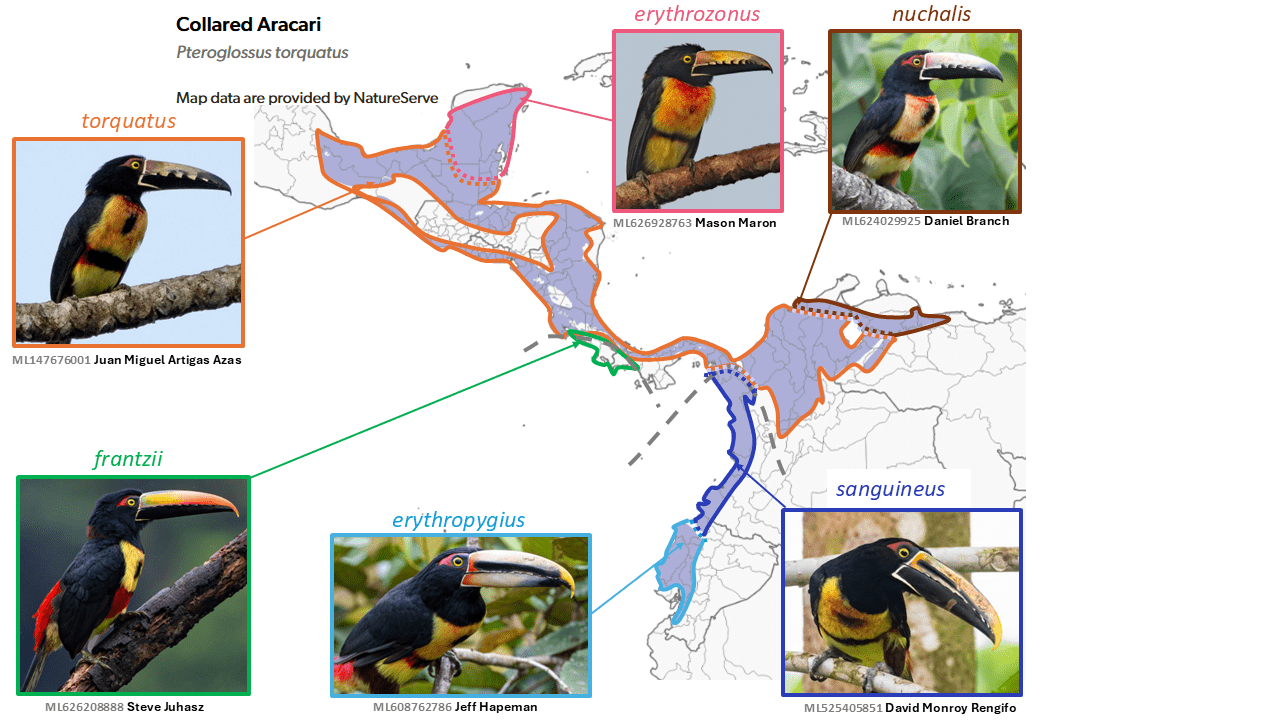

Pale-mandibled Aracari Pteroglossus erythropygius is split from Collared Aracari Pteroglossus torquatus

Summary: (1→2 species) Two aracaris that hybridize in a narrow zone in far northern Colombia differ in bill structure and in genetics, and are now considered separate species, the Collared Aracari in Middle America and northern South America, and the Pale-mandibled Aracari in northwestern South America.

Details: v2025 taxa 10885–10891

Was:

- Collared Aracari Pteroglossus torquatus

- subspecies torquatus, erythrozonus, nuchalis, sanguineus, and erythropygius

Now:

- Collared Aracari Pteroglossus torquatus

- subspecies torquatus, erythrozonus, and nuchalis

- Pale-mandibled Aracari Pteroglossus erythropygius

- subspecies sanguineus and erythropygius

Graphical Abstract:

The Collared Aracari Pteroglossus torquatus (Gmelin, 1788) is the most widely distributed member of its genus in Mesoamerica, and four component taxa also reach northwestern South America. In addition, the closely related Fiery-billed Aracari Pteroglossus franzii Cabanis, 1861 occurs in southwestern Central America. Peters (1948) treated the complex as comprising three species, with frantzii a subspecies of torquatus, and the two primarily western South American taxa sanguineus Gould, 1854 and erythropygius Gould, 1843 as separate species. Haffer (1974), followed by Wolters (1976), treated all these as subspecies of torquatus, based largely on evidence of hybridization, although the hybrid zone (which Haffer 1974 called ‘uninhibited’) in southeastern Panama between torquatus and sanguineus appears to be narrow, and no hybrid zone is known between torquatus and frantzii, which instead appear to be parapatric or even narrowly sympatric. Hybridization between erythropygius and sanguineus in northwestern Ecuador appears to be common (Short and Horne 2001), and this seems to be borne out in ML photos. AOS (1998) treated erythropygius as a species but not sanguineus. Several other authors have treated all as separate species (e.g., Ridgely and Greenfield 2001), without providing detailed rationale.

In a phylogeny based on mtDNA and a nuclear intron (Patel et al. 2011), frantzii is sister to a clade formed by erythropygius and sanguineus, with torquatus sister to these two clades. Morphologically, frantzii is the most distinctive in plumage, while it and erythropygius and sanguineus differ conspicuously from the torquatus group in the number and development of tomial ‘teeth’. SACC last considered this issue in 2004 and narrowly rejected it then. AviList Core Team (2025) takes a two-species approach, as outlined above, and in addition continues to recognize frantzii as a full species.

English names: The English name Pale-mandibled Aracari tentatively adopted for one daughter species has a history of use (del Hoyo and Collar 2014). However, given that here the species Pteroglossus erythropygius also includes the taxon sanguineus, which has a dark mandible, it is only apt for taxon erythropygius, and further consideration is needed.

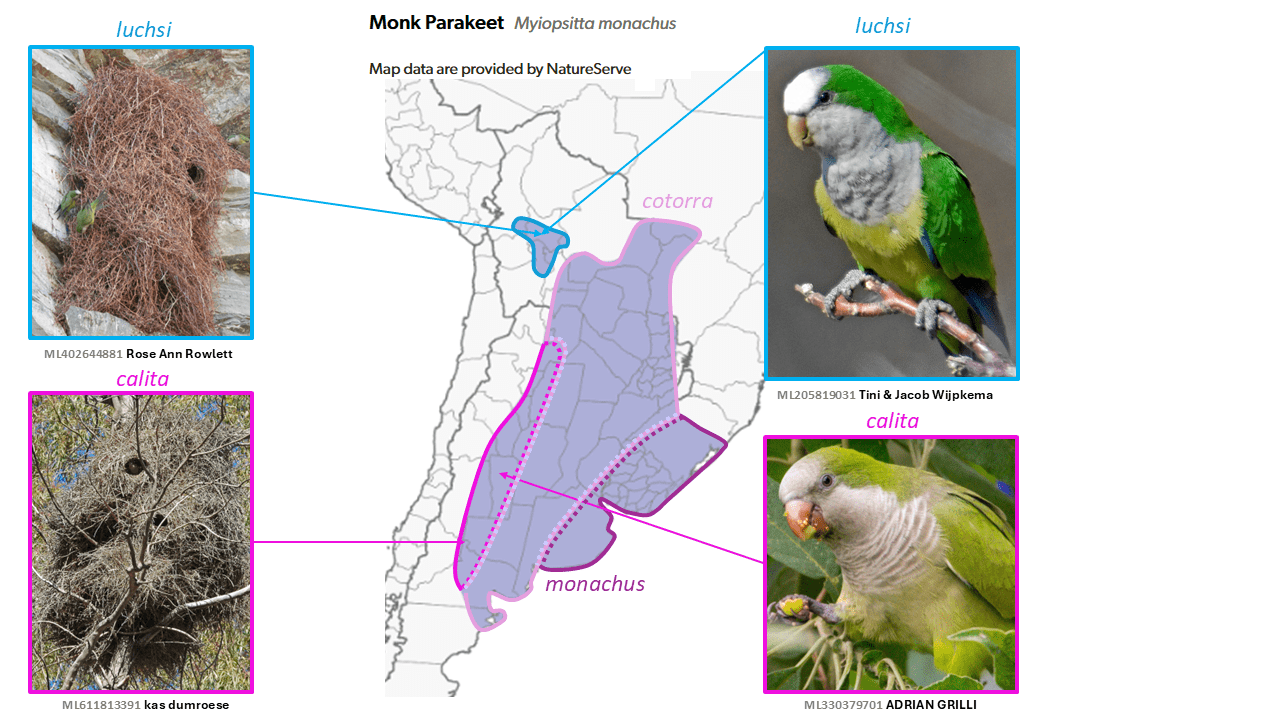

Cliff Parakeet Myiopsitta luchsi is split from Monk Parakeet Myiopsitta monachus

Summary: (1→2 species) Bolivia gains a new endemic with the split of the Cliff Parakeet from the widespread Monk Parakeet of central and southern South America, from which it differs in breeding habits and voice.

Details: v2025 taxa 12819–12822

Was:

- Monk Parakeet Myiopsitta monachus

- subspecies cotorra, monachus, calita, and luchsi

Now:

- Monk Parakeet Myiopsitta monachus

- subspecies cotorra, monachus, and calita

- Cliff Parakeet Myiopsitta luchsi (monotypic)

Graphical abstract:

Throughout most of its wide range in southern South America (and locally in North America, Europe, Israel, and elsewhere as a result of introductions), the Monk Parakeet Myiopsitta monachus (Boddaert, 1783) is well-known for its remarkable communal stick nests that are normally placed in trees, or these days on power poles and the like. In contrast, in central Bolivia, the taxon luchsi (Finsch, 1868) (which was originally described as a species) builds similar communal nests but exclusively on cliff faces, even where trees are present. In addition, luchsi differs consistently from the other taxa in plumage, especially its unscaled breast; in its vocalizations (though no published vocal analysis exists); in mtDNA (Russello et al. 2008); and in UCE data (Smith et al. 2023). Furthermore, evidence of hybridization is not known despite their parapatry. Although two earlier proposals to SACC failed, as did the first one to AviList, the accumulation of further evidence, especially sound recordings, has led to its specific status now being accepted by both SACC and AviList Core Team (2025).

English names: The names adopted here, Cliff Parakeet and Monk Parakeet, have been widely used previously. In addition, Cliff Parakeet aptly describes the breeding habitat chosen by this taxon, in strong contrast to that of the Monk Parakeet, a very familiar and deeply embedded name for this widespread species.

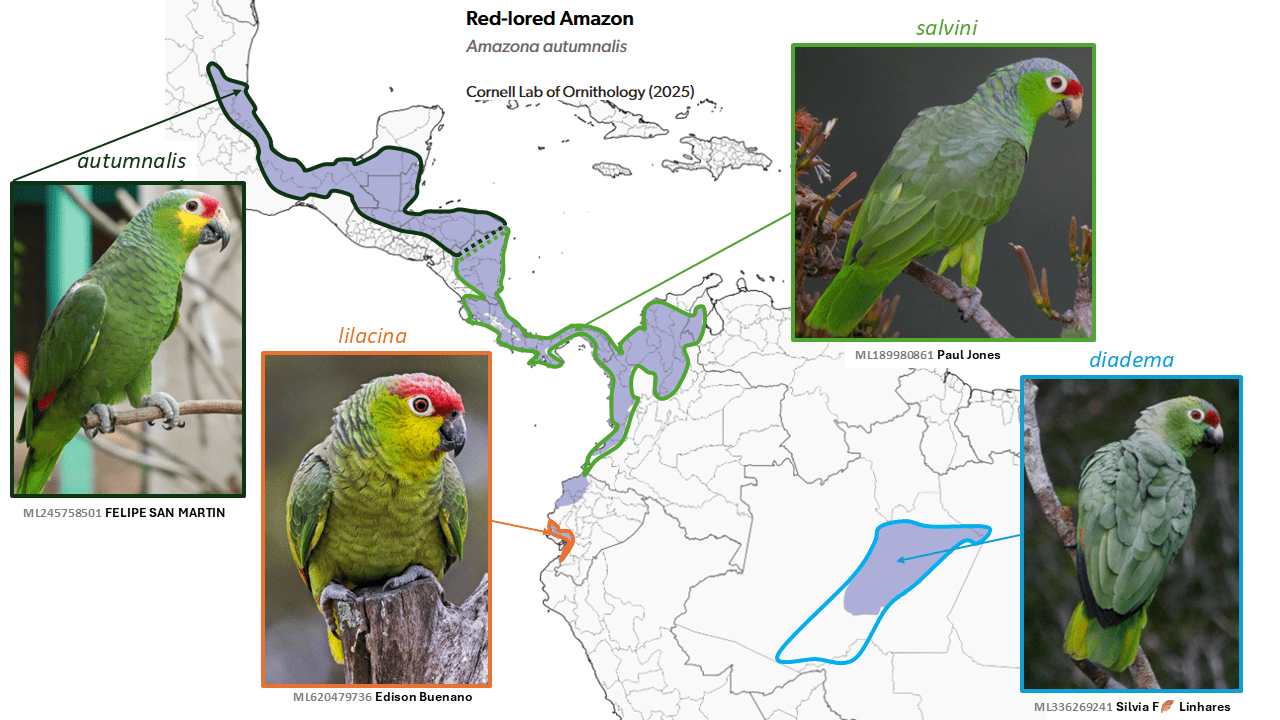

Red-lored Amazon Amazona autumnalis, Lilacine Amazon Amazona lilacina, and Diademed Amazon Amazona diadema are split from Red-lored Amazon Amazona autumnalis

Summary: (1→3 species) One of the most familiar amazons in Middle America, the Red-lored Amazon, is much less so in the Ecuador and Brazil populations, and these two little-known isolates are now considered separate species, the Lilacine and Diademed amazons.

Details: v2025 taxa 12909–12915

Was:

- Red-lored Amazon Amazona autumnalis

- subspecies autumnalis, salvini, lilacina, and diadema

Now:

- Red-lored Amazon Amazona autumnalis

- subspecies autumnalis and salvini

- Lilacine Amazon Amazona lilacina (monotypic)

- Diademed Amazon Amazona diadema (monotypic)

Graphical abstract:

Four taxa treated by most authorities (including Wolters 1975) as conspecific under Amazona autumnalis (Linnaeus, 1758) at least since Peters (1937) were originally described as full species: autumnalis of Mexico to northern Central America; salvini (Salvadori, 1891) of central Central America to northern South America; lilacina Lesson, 1844 of coastal Ecuador; and diadema (Spix, 1824) of a limited area in central Amazonia. While autumnalis and salvini are common and well-known, diadema is a rather mysterious and broadly allopatric Amazonian taxon, and lilacina is a rather rare and local mangrove-roosting species of coastal southwestern Ecuador (Freile and Restall 2018) that may be parapatric with salvini (Donegan et al. 2016), although current roost sites are well south of the range of salvini (Biddle et al. 2020), and reports from northwestern Ecuador require validation.

Based largely on multiple morphological differences, del Hoyo and Collar (2014) considered there to be three species in the complex, in splitting both lilacina and diadema. Genetic data are contradictory and thus inconclusive (Ottens-Wainright et al. 2004, Russello and Amato 2004, Pilgrim 2010, Smith et al. 2023). A recent proposal to SACC narrowly failed, but the three-way split was adopted by AviList Core Team (2025).

English names: The previously used English names (del Hoyo and Collar 2014) of Red-lored Amazon, Lilacine Amazon, and Diademed Amazon for the daughter and parent species were tentatively adopted.

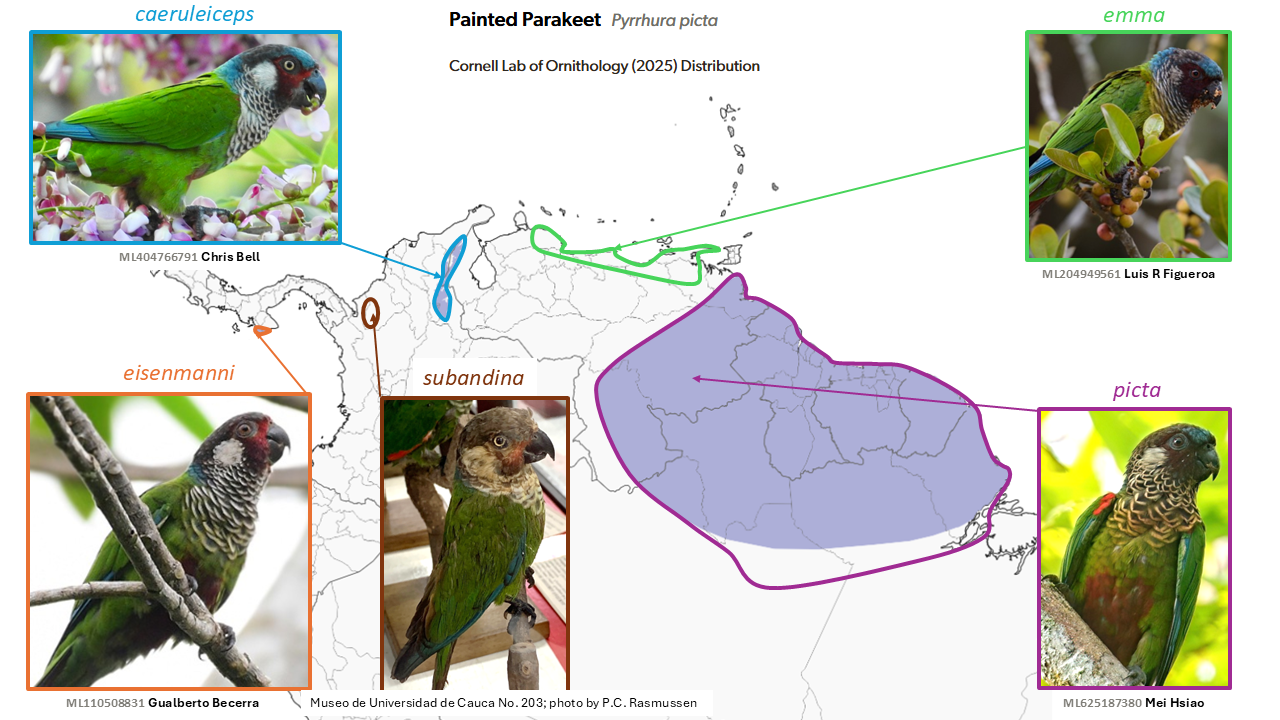

Painted Parakeet Pyrrhura picta is split into four species

Summary: (1→4 species) The colorful Painted Parakeet is now treated as four species, most of which are narrow endemics in northern South America.

Details: v2025 taxa 13034–13039

Was:

- Painted Parakeet Pyrrhura picta

- subspecies eisenmanni, subandina, caeruleiceps, emma, and picta

Now:

- Subandean Parakeet Pyrrhura subandina

- subspecies eisenmanni and subandina

- Perija Parakeet Pyrrhura caeruleiceps (monotypic)

- Venezuelan Parakeet Pyrrhura emma (monotypic)

- Painted Parakeet Pyrrhura picta (monotypic)

Graphical abstract:

Few avian taxa have as complicated taxonomic histories as do the Neotropical Pyrrhura parakeets, as illustrated by a 2007 SACC proposal to split the P. picta (Müller, 1776) and P. leucotis complexes, based partly on Ribas et al. (2006). Despite this rearrangement, subsequent molecular work (Smith et al. 2023) indicates that the current treatment of the picta complex of northern South America and southwestern Panama involves several cases of non-monophyly with other taxa normally considered different species. Differences in plumage and iris color between these broadly allopatric taxa further suggest the necessity of taxonomic revision.

Uncertainty remains, particularly with respect to the treatment of the taxon eisenmanni Delgado, 1985 of the Azuero Peninsula, south-central Panama, as conspecific with the taxon subandina Todd, 1917 of the Sinú Valley of northwestern Colombia (the latter now perhaps extinct). Nevertheless, a four-species treatment has been adopted by AviList Core Team (2025): subandina; picta (of the Guianan Shield to Brazil north of the Amazon River); emma (of northern Venezuela); and caeruleiceps (of the Perijá Mountains on the border of northeastern Colombia and northwestern Venezuela).

English names: Three of the English names used by del Hoyo and Collar (2014) for the split taxa are tentatively adopted here: Painted Parakeet for Pyrrura picta s.s.; Venezuelan Parakeet for Pyrrhura emma; and Perija Parakeet for Pyrrhura caeruleiceps. The latter two seem uncontroversial and apt, while retention of the former (Painted) for just one of the isolates may lead to confusion. An alternative suggestion would be Guianan Parakeet for P. picta s.s., although its range extends somewhat beyond this region. For the combined species subandina and eisenmanni, no very apt name has been found and the name Subandean Parakeet, which mirrors the species epithet, is tentatively used but is not a good fit for Panamanian eisenmanni.

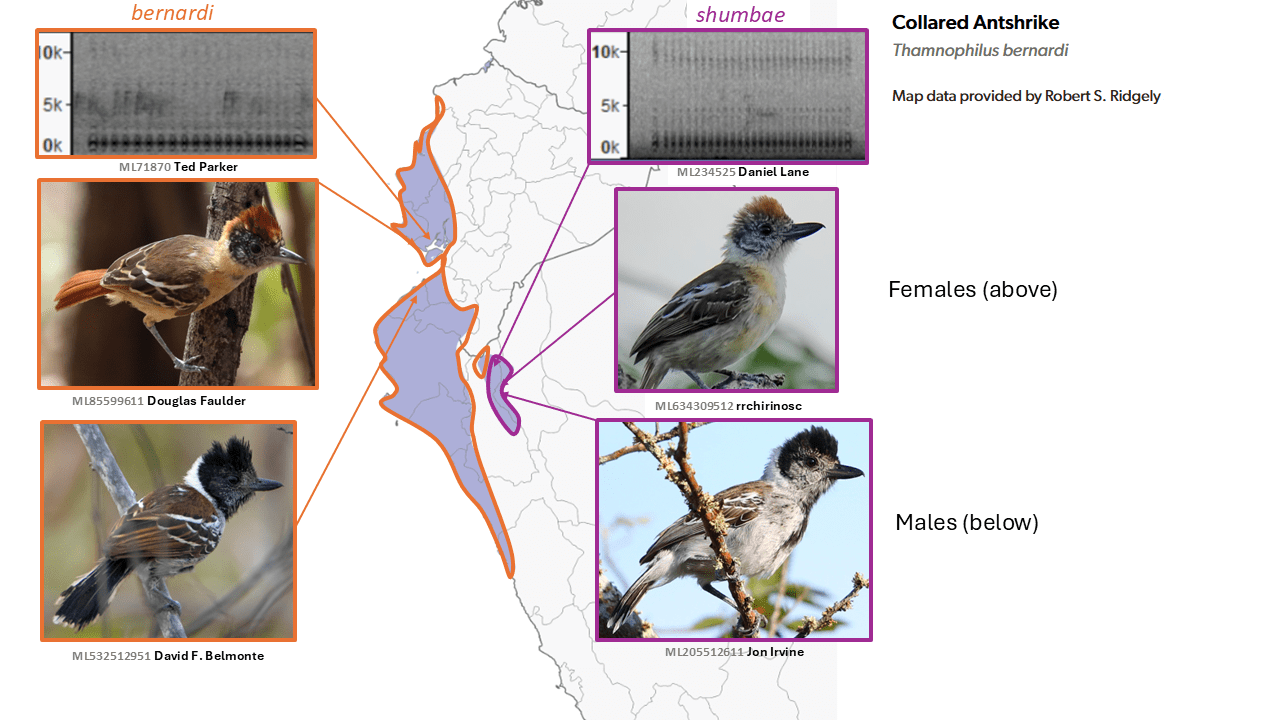

Marañon Antshrike Thamnophilus shumbae is split from Collared Antshrike Thamnophilus bernardi

Summary: (1→2 species) The Marañon Antshrike from its namesake valley in Peru sings a much faster song than the closely related Collared Antshrike, despite occurring in close proximity.

Details: v2025 taxa 13532–13533

Was:

- Collared Antshrike Thamnophilus bernardi

- subspecies bernardi and shumbae

Now:

- Collared Antshrike Thamnophilus bernardi (monotypic)

- Marañon Antshrike Thamnophilus shumbae (monotypic)

Graphical abstract:

A notable difference in song pace between Thamnophilus bernardi Lesson, 1844 mainly of western Ecuador and western Peru, and the inland taxon shumbae (Carriker, 1934) from the Marañón Valley of northern Peru is well-known (Schulenberg et al. 2007, Boesman 2016: 54). This, coupled with plumage differences, would seem to be sufficient for species rank in this group in which vocalizations are key. Although shumbae was originally described as a subspecies of bernardi and treated as such nearly universally, including by Peters (1951), it was elevated by del Hoyo and Collar (2016) to species status. However, the situation is complicated by intrusion of bernardi into the Marañón Valley as well, leading to uncertainty as to the nature of their interactions, and more recently by evidence for considerable gene flow between them by Oswald et al. (2017). This led to initial failure of the AviList motion to split shumbae.

However, unpublished data indicating parapatry and lack of response to playback to each others’ songs, with strong response to their own songs (Zimmer, in SACC proposal 1000, which narrowly failed) eventually led to the conclusion upon a revote by AviList Core Team (2025) that shumbae and bernardi are best treated as separate species.

English names: The long-standing, familiar name Collared Antshrike remains the best choice for bernardi, while the name Maranon Antshrike as used by del Hoyo and Collar (2016) for shumbae, but standardized as Marañon for consistency with other taxa thus named in the eBird/Clements checklist, is tentatively adopted here.

Black-capped Antthrush Formicarius nigricapillus and Black-hooded Antthrush Formicarius destructus are split from Black-headed Antthrush Formicarius nigricapillus

Summary: (1→2 species) Southern Central America and the Chocó region of northwestern South America each gain another difficult-to-see endemic, with the split of the Black-capped Antthrush from the Black-hooded Antthrush.

Details: v2025 taxa 14492–14493

Was:

- Black-headed Antthrush Formicarius nigricapillus

- subspecies nigricapillus and destructus

Now:

- Black-capped Antthrush Formicarius nigricapillus (monotypic)

- Black-hooded Antthrush Formicarius destructus (monotypic)

Graphical abstract:

Two disjunct antthrush taxa long treated as conspecific (at least since Peters 1951), Formicarius nigricapillus Ridgway, 1893 of montane Costa Rica and Panama, and destructus Hartert, 1898 of lowlands of the Chocó bioregion of northwestern South America, have been shown to differ in plumage, morphometrics, and song (Areta and Benítez Saldívar 2025). The form destructus (so named because the type specimen was “very much destroyed by the shot”; Hartert 1898) was originally described as a subspecies of Formicarius analis (in which species Hartert also placed nigricapillus), but has been considered a subspecies of nigricapillus since at least Chapman (1917), and was thus treated by the influential Peters (1951). Only rarely has destructus been considered a full species (Salvadori and Festa 1899, Howell and Dyer 2022). However, following the comprehensive analysis by Areta and Benítez Saldívar (2025), SACC, NACC (Areta and Benítez Saldívar 2025, 2025-D-2), and AviList Core Team (2025) have all accepted the split.

English names: The retention of the name Black-headed Antthrush for either daughter species has been deemed unsatisfactory in this case, given their approximately similar-sized distributions and levels of familiarity. However, the subtlety of distinguishing phenotypic characteristics, and the presence of other antthrush species in their ranges has made decisions about English names difficult. The names ultimately agreed upon by SACC and thus adopted here, Black-capped Antthrush for Formicarius nigricapillus s.s. and Black-hooded Antthrush for Formicarius destructus, reflect differences in their plumage, and the former mirrors the specific epithet.

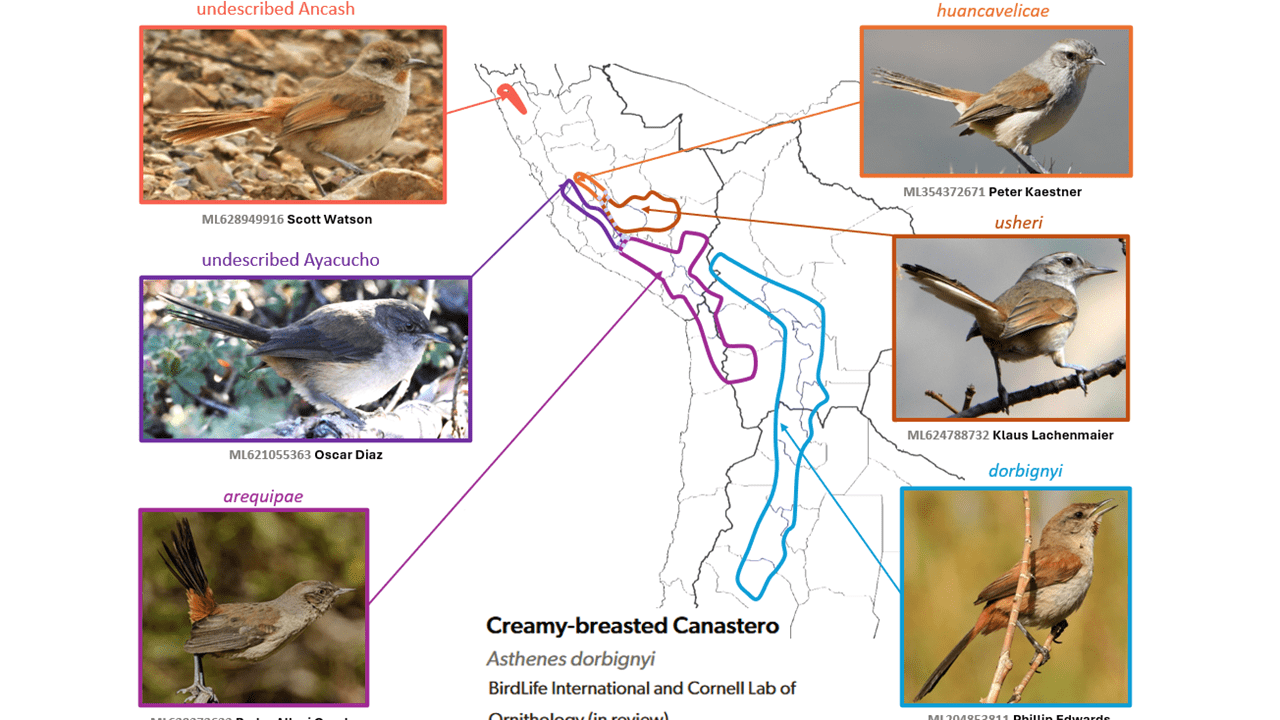

Creamy-breasted Canastero Asthenes dorbignyi is split into three species

Summary: (1→3 species) Peru is the epicenter of diversity of the former Creamy-breasted Canastero, and multiple species have long been known from there, of which we recognize three, and await the description of two others.

Details: v2025 taxa 15375–15382

Was:

- Creamy-breasted Canastero Asthenes dorbignyi

- subspecies huancavelicae, arequipae, usheri, consobrina, and dorbignyi

Now:

- Pale-tailed Canastero Asthenes huancavelicae

- subspecies huancavelicae and usheri

- Dark-winged Canastero Asthenes arequipae (monotypic)

- Rusty-vented Canastero Asthenes dorbignyi

- subspecies consobrina and dorbignyi

Graphical abstract:

Few species complexes are beset by as many as two long-undescribed taxa, as in the case of the Creamy-breasted Canastero Asthenes dorbignyi. All taxa were treated as conspecific by Peters (1951): huancavelica Morrison, 1938; usheri Morrison, 1947; arequipae (Sclater & Salvin, 1869); consobrina Hellmayr, 1925; and dorbignyi (Reichenbach, 1853), to the exclusion of the western Bolivian Asthenes berlepschi (Hellmayr, 1917).

The situation is described in the early SACC proposal, in which near-certainty about multiple species being involved was expressed but the proposal failed due to the details remaining unpublished. That there are at least two unnamed taxa in the complex and that all taxa are believed to be allopatric, parapatric, or altitudinally segregated was indicated by Fjeldså and Krabbe (1990). Additionally, they are considered to differ vocally and to lack evidence of intergradation (Fjeldså and Krabbe 1990, Boesman 2016: 96). Ridgely and Tudor (1994) treated the complex as comprising three described species, and they were followed in this by the IOC-WBL from v.1.0, while del Hoyo and Collar (2016) treated the described taxa of the complex as comprising four species. Harvey et al. (2020) showed on the basis of genomic data that the longstanding single-species treatment of this complex to the exclusion of Asthenes berlepschi (Hellmayr, 1917) [which is narrowly allopatric in the Upper Río Consata drainage, in La Paz, western Bolivia, and was said by Fjeldså and Krabbe (1990) to possibly be best treated as a subspecies of arequipae] creates an instance of paraphyly.

Given that a three-species treatment of the described taxa is surely closer to the best solution than is the unjustified lump of all, which would have to include berlepschi, AviList Core Team (2025) agreed to an interim three-way split of the erstwhile dorbignyi s.l. Thus, the species here recognized are:

- Pale-tailed Canastero Asthenes huancavelicae, with subspecies huancavelicae (of the Río Mantaro drainage of Huancavelica and western Ayacucho, central Peru at about 3350–3700 m) and usheri (of the Pampas and upper Apurímac drainages of south-central Peru in northeastern Ayacucho, Apurímac, and southwestern Cusco, at 2150–3800 m (Schulenberg et al. 2007);

- Dark-winged Canastero Asthenes arequipae of the western slope of the Andes of southwestern Peru of Lima and Ayacucho southward to western Bolivia and northern Chile; and

- Rusty-vented Canastero Asthenes dorbignyi, with subspecies consobrina of the Andes of northwestern Bolivia, and subspecies dorbignyi of the Andes from central Bolivia to northwestern Argentina.

In addition, there are undescribed taxa, one each presumably in the species delineated as huancavelica and arequipae (Fjeldså and Krabbe 1990).

English names: The English names tentatively adopted have been in long usage at least since the publication of Fjeldså and Krabbe (1990), and are reasonably apt and utilitarian for these subtly plumaged taxa.

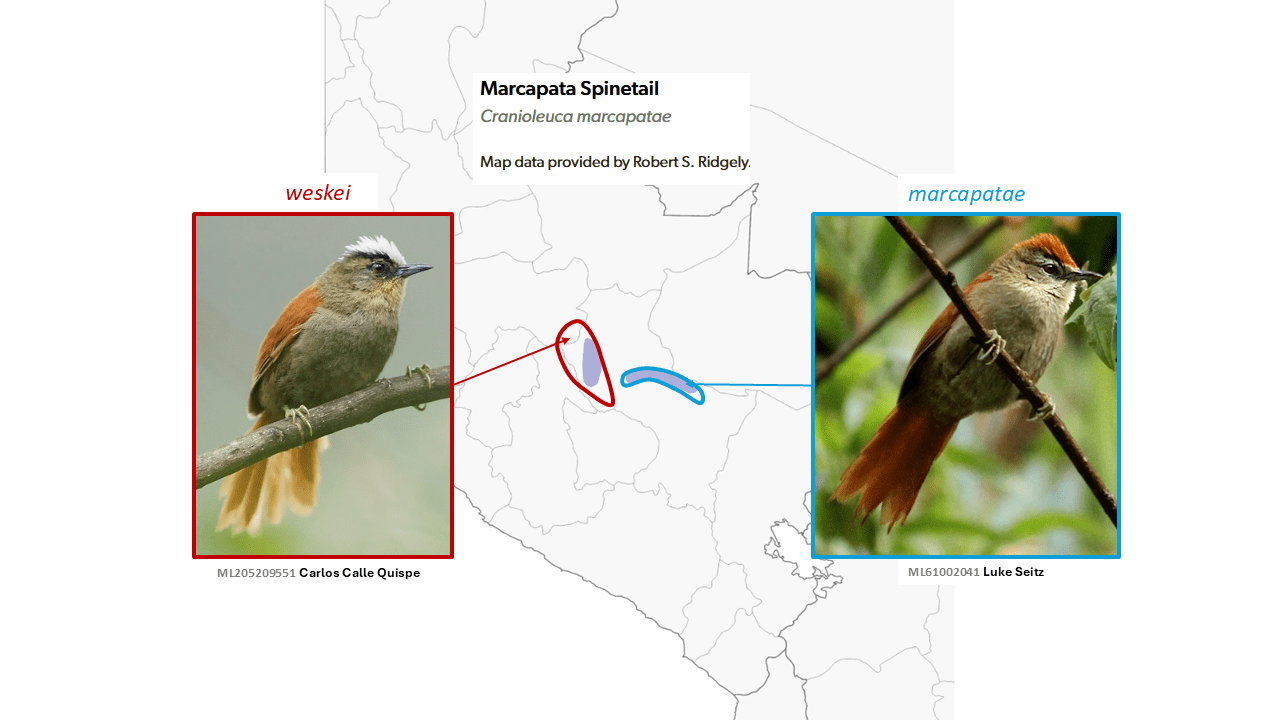

Vilcabamba Spinetail Cranioleuca weskei is split from Marcapata Spinetail Cranioleuca marcapatae

Summary: (1→2 species) Two central Peruvian spinetails with strikingly colored crowns, one white and the other one bright chestnut, seem not to mix despite close approach, and are thus now considered species.

Details: v2025 taxa 15485–15486

Was:

- Marcapata Spinetail Cranioleuca marcapatae

- subspecies marcapatae and weskei

Now:

- Marcapata Spinetail Cranioleuca marcapatae (monotypic)

- Vilcabamba Spinetail Cranioleuca weskei (monotypic)

Graphical abstract:

The taxon Cranioleuca marcapatae Zimmer, 1935 is limited in distribution to a narrow zone in central Cusco, while the recently described weskei Remsen, 1984 is now known to be found more widely in south-central Peru (including the Mantaro Valley in southeastern Junín, northern Ayacucho, and southward to Cordillera Vilcabamba in Cusco). Although earlier thought to be widely allopatric, the two occur within some 40 km of each other (Seeholzer in SACC proposal 1010), and the intervening valleys do not appear to present an insurmountable barrier based on the distribution of weskei across other river valleys. While the initial treatment of weskei as a subspecies was based partly on analogy of crown color variation from rufous to white in the related Cranioleuca albiceps (d’Orbigny & de Lafresnaye, 1837), and the expectation that such would likely be found to be the case with weskei and marcapatae, that has not proven to be the case, with photos of even those individuals nearest each others’ ranges being clearly white or clearly rufous. However, reports of possible intergradation (Hosner et al. 2015) over a narrow zone require further study.

In addition, differences in vocalizations have been documented (Boesman 2016: 100), although intrataxon variation and sample sizes are a problem, and further study is also required on this aspect. On the basis of phenotypic and vocal differences, del Hoyo and Collar (2016) treated weskei as a separate species from marcapatae. This is now the treatment adopted by SACC and AviList Core Team (2025).

English names: Given their respective river-valley distributions, the names Marcapata Spinetail for Cranioleuca marcapatae and Vilcabamba Spinetail for Cranioleuca weskei, which were used by del Hoyo and Collar (2016), have been adopted by SACC and followed here. Nevertheless, confusion due to the retention of the parent species name for one of the daughter species is possible, but seems not to be a major problem, as both taxa are narrowly distributed within one region of a single country, Peru.

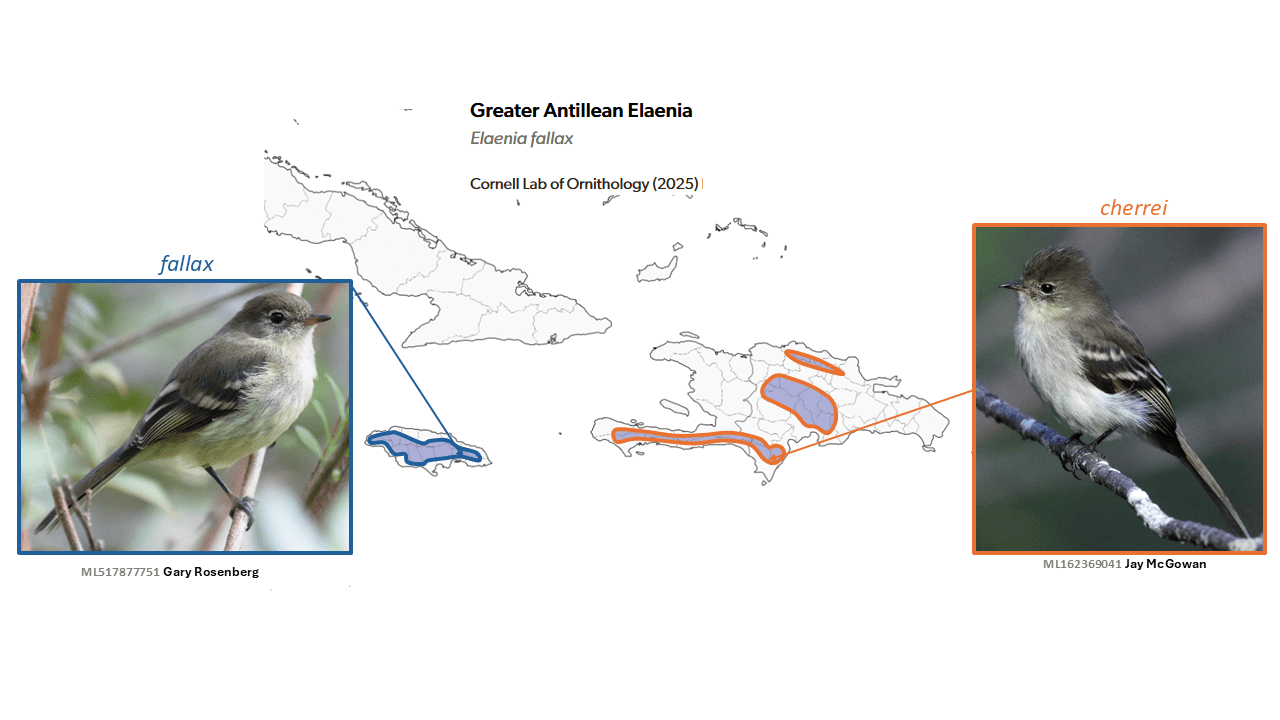

Blue Mountain Elaenia Elaenia fallax and Hispaniolan Elaenia Elaenia cherriei are split from Greater Antillean Elaenia Elaenia fallax

Summary: (1→2 species) Two West Indian islands now each host yet another endemic bird species, with the split of Greater Antillean Elaenia into Blue Mountain Elaenia and Hispaniolan Elaenia.

Details: v2025 taxa 16743–16744

Was:

- Greater Antillean Elaenia Elaenia fallax

- subspecies fallax and cherriei

Now:

- Blue Mountain Elaenia Elaenia fallax (monotypic)

- Hispaniolan Elaenia Elaenia cherriei (monotypic)

Graphical abstract:

Among elaenias of the genus Elaenia, morphological differences are typically minimal. Thus the long-term (since Hellmayr 1927, continued by Traylor 1979 in volume 8 of the Peters Check-list) retention of the diagnosably different Elaenia cherrei Cory, 1895 of Hispaniolan hills as conspecific with Elaenia fallax Sclater, 1861 of Jamaican highlands requires reevaluation. del Hoyo and Collar (2016) were the first in many years to treat the two as separate species, citing molecular divergence (Rheindt et al. 2008), morphology, and vocal differences among a small sample. With the benefit of the much larger sample of online recordings now available, AviList Core Team (2025) agreed to a two-species treatment. However, a 2022 proposal to NACC (Stotz 2022, 2022-C-15) failed, largely on the basis that vocal comparisons remain unpublished, and appear to be in conflict with statements about vocalizations in e.g. Kirwan et al. (2019, 2021), as well as lack of agreement on the species-delimitation value of genetic divergence and the often-higher levels of divergence between insular taxa than mainland ones.

English names: As there is already a taxon known long and widely as the Jamaican Elaenia Myiopagis cotta (Gosse, 1849), this name is not an option for the split fallax. However, despite the failure of the proposal to pass NACC, the name Blue Mountain Elaenia for this highland species found wide favor, and is tentatively adopted here for fallax s.s. Hispaniolan Elaenia seems a non-controversial name for cherrei, and is also tentatively adopted here. del Hoyo and Collar (2016), however, used Large Jamaican Elaenia for Elaenia fallax s.s. and Small Jamaican Elaenia for Myiopagis cotta, but this suggests a close relationship that does not exist. J. Boyd suggested the eponym Sclater’s Elaenia for Elaenia fallax s.s.

Salvadoran Flycatcher Myiarchus flavidior is split from Nutting’s Flycatcher Myiarchus nuttingi

Summary: (1→2 species) Yet another difficult-to-identify flycatcher species is now recognized, the Salvadoran Flycatcher, which can however best be identified by its distinctive voice.

Details: v2025 taxa 17326–17329

Was:

- Nutting’s Flycatcher Myiarchus nuttingi

- subspecies inquietus, nuttingi, and flavidior

Now:

- Nutting’s Flycatcher Myiarchus nuttingi

- subspecies inquietus and nuttingi

- Salvadoran Flycatcher Myiarchus flavidior (monotypic)

Graphical abstract:

Another of the most taxonomically fraught genera in Class Aves (comparable to Elaenia) is Myiarchus, whose taxonomy was greatly improved by the pioneering and comprehensive field and museum studies of W. E. Lanyon, when sound recording was much more difficult than it is today. One of the many taxonomic conundra Lanyon resolved was the demonstration of specific distinctness of the Middle American Nutting’s Flycatcher Myiarchus nuttingi Ridgway, 1882 (originally described as a species) from Ash-throated Flycatcher Myiarchus cinerascens (Lawrence, 1851) (Lanyon 1961). His recommended treatment of a three-subspecies Myiarchus nuttingi (including nuttingi, flavidior, and inquietus Salvin & Godman, 1889) distributed from northern Mexico to northwestern Costa Rica was followed by Traylor (1979), in the eighth volume of the Peters Check-list, and thus by subsequent authorities.

However, further problems remained in the complex that were beyond the scope of Lanyon’s (1961) study, as highlighted by Howell (2012), who considered that two species must be involved in M. nuttingi. After much further fieldwork and related study, Howell et al. (2024) have shown that the taxon flavidior Van Rossem, 1936, which was described as a subspecies of cinerascens and then placed in M. nuttingi, is diagnosably different in plumage and habitat, and has some quite distinct vocalizations. Additionally, Howell et al.’s (2024) analysis of voucher specimens demonstrated that Sari and Parker (2012) had evidently molecularly sampled both flavidior and nuttingi, which were non-monophyletic and deeply diverged in their study.

Proposal 2025-A-4 to NACC, by Juárez et al. to recognize flavidior as specifically distinct has passed, and AviList Core Team (2025) has accepted this recommendation. It should be noted, however, that vocal differences appear to exist between nuttingi and inquietus as well, and thus their taxonomic status requires further study.

English names: For the widespread Nutting’s Flycatcher Myiarchus nuttingi, the longstanding eponym that mirrors its specific epithet has been retained, while for the much more range-restricted Myiarchus flavidior, the name Salvadoran Flycatcher was chosen by NACC, as that country forms its core range, although it also occurs from southernmost Mexico to western Honduras and northernmost Nicaragua.

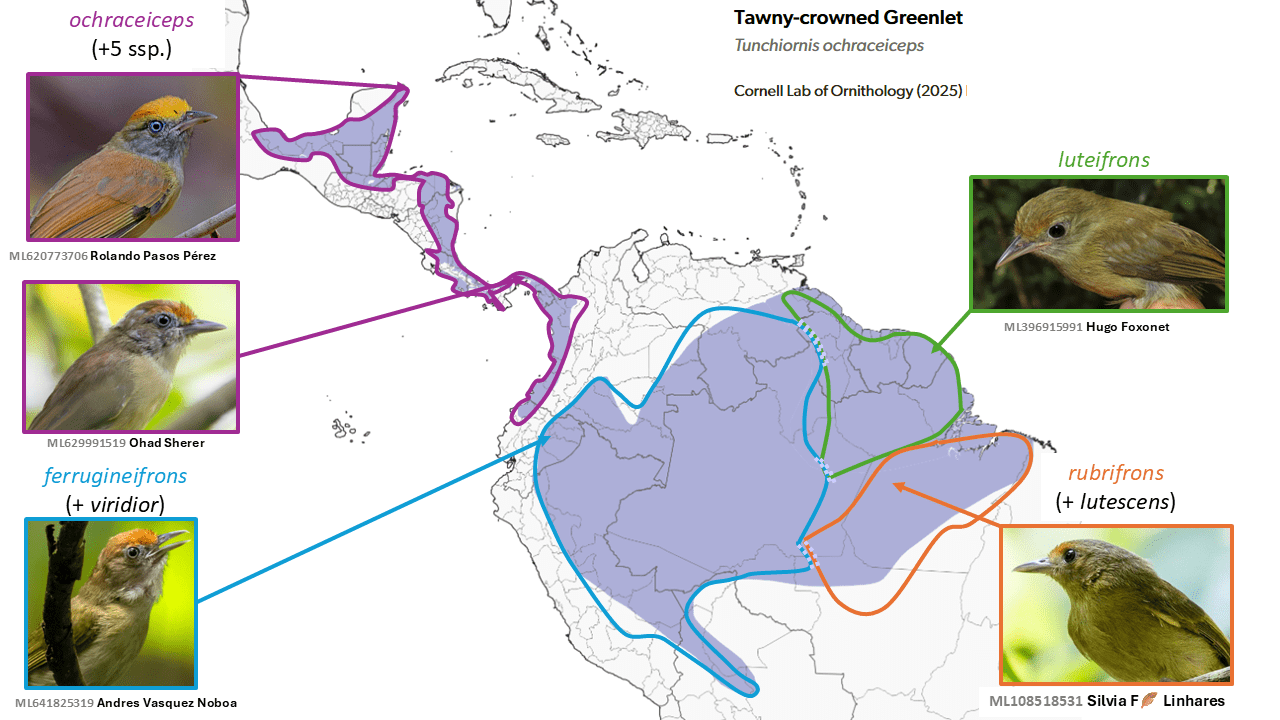

Tawny-crowned Greenlet Tunchiornis ochraceiceps is split into four species

Summary: (1→4 species) One of the many small Neotropical vireos known as greenlets (though they lack any green), the Tawny-crowned Greenlet is now known not only to be in a different genus, but to represent four species, mostly in Middle America and Amazonia.

Details: v2025 taxa 19122–19134

Was:

- Tawny-crowned Greenlet Tunchiornis ochraceiceps

- subspecies ochraceiceps, pallidipectus, nelsoni, bulunensis, ferrugineifrons, viridior, luteifrons, lutescens, and rubrifrons

Now:

- Ochre-crowned Greenlet Tunchiornis ochraceiceps

- subspecies ochraceiceps, pallidipectus, nelsoni, and bulunensis

- Rufous-fronted Greenlet Tunchiornis ferrugineifrons

- subspecies ferrugineifrons and viridior

- Guianan Greenlet Tunchiornis luteifrons (monotypic)

- Para Greenlet Tunchiornis rubrifrons

subspecies lutescens and rubrifrons

Graphical abstract:

Formerly considered just one species in the genus Hylophilus, the long-standing species construct known as Tawny-crowned Greenlet has been shown to require its own genus, which was named Tunchiornis (Slager et al. 2014, Slager and Klicka 2014). Although conservatively plumaged, four taxa that were all originally described at the species level, ochraceiceps (Sclater, 1860), ferrugineifrons (Sclater, 1862), luteifrons (Sclater, 1881), and rubrifrons (Sclater and Salvin, 1867) but were long treated as conspecific (e.g. Blake 1968, in Volume 14 of Peters’ Check-list) were shown to be deeply diverged genetically, well above the level usually associated with specific distinctness (Slager et al. 2014, Buainain et al. 2021). Most of the contact zones are across major rivers, or the Andes, and require further study. Some vocal differences are evident (Boesman 2016: 168, Buainain et al. 2021), especially between Guianan Shield luteifrons and the rest, but there is inconsistency and overlap, and voice has not yet been clearly demonstrated to be diagnostic of these other deeply diverged groups. In addition to genetics and voice, it is notable that western taxa have pale irides, while eastern ones have dark irides. del Hoyo and Collar (2016) considered luteifrons to be a separate species, but on the basis of the genetic results, a four-species treatment has been accepted by SACC and AviList Core Team (2025).

English names: While this issue is still under discussion by SACC, the tentative English names above are used to denote the daughter species, and thus these are likely to change.

Eastern Warbling Vireo Vireo gilvus and Western Warbling Vireo Vireo swainsoni are split from Warbling Vireo Vireo gilvus

Summary: (1→2 species) Despite looking very similar, North America’s Eastern and Western Warbling Vireos know how to tell; they prefer different habitats, where they sing differently, among other differences.

Details: v2025 taxa 19245–19251

Was:

- Warbling Vireo Vireo gilvus

- subspecies gilvus, swainsoni, victoriae, brewsteri, and sympatricus

Now:

- Eastern Warbling Vireo Vireo gilvus (monotypic)

- Western Warbling Vireo Vireo swainsoni

- subspecies swainsoni, victoriae, brewsteri, and sympatricus

Graphical abstract:

The Warbling Vireo Vireo gilvus (Vieillot, 1808) is one of eastern North America’s most familiar songbirds (when heard), and is largely associated with trees at the edges of wetlands. In western North America, in contrast, taxa of the swainsoni Baird, 1858 group are more typically forest birds, occurring into the mountains, with song that differs noticeably from nominate gilvus. A large number of studies that bear on their species-level taxonomy (e.g., Voelker and Rohwer 1998, Lovell 2010, Spencer 2012, Browning 2019, Sealy et al. 2000, Slager et al. 2014, Lovell et al. 2021, Carpenter et al. 2022a, b) have been carried out over many years, and taken together they show that these very similar-looking birds differ in a great many ways that are atypical of subspecies. They are deeply diverged genetically, they hybridize rather infrequently in a zone of sympatry, they prefer different habitats, their songs differ, they have different molt schedules, and they differ in response to cowbird parasitism. They were originally described as separate species, and there are also several morphological differences on average, but these are often difficult to perceive, even in good photographs.

Based on the cumulative weight of evidence, which is far greater than that available for the vast majority of such decisions, NACC (based on a proposal by Cicero 2025, 2025-C-3) and AviList Core Team (2025) have voted to treat gilvus as a separate species from the swainsoni group, now a species. Further study is needed regarding the taxonomic status of the isolated taxon in the mountains of the Cape region of southern Baja California Sur, victoriae Sibley, 1940, which is larger-billed than other taxa sampled of the swainsoni group, and was eventually elevated to species status by Sibley (1996).

English names: Both taxa have long been known as Warbling Vireo, and the English names Eastern Warbling Vireo (whether hyphenated, as by NACC, or not) and Western Warbling Vireo have been used for many years in many studies, and were adopted by NACC (Chesser et al. 2025) and AviList.

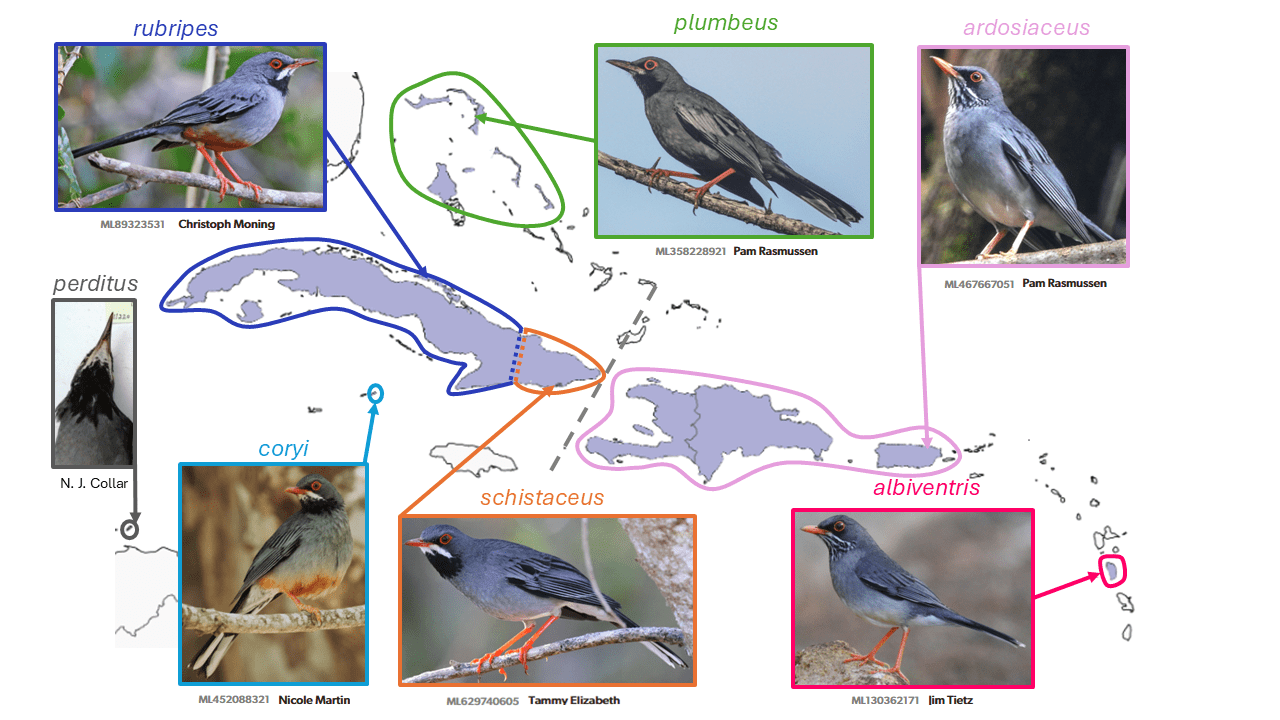

Western Red-legged Thrush Turdus plumbeus and Eastern Red-legged Thrush Turdus ardosiaceus are split from Red-legged Thrush Turdus plumbeus

Summary: (1→2 species) While the Bahamas and Cuba share several bird species unique to that region, Hispaniola and Puerto Rico do not, but the newly split Eastern Red-legged Thrush is very similar on the latter two islands, and (surprisingly) also occurs on far-flung Dominica.

Details: v2025 taxa 28619–28629

Was:

- Red-legged Thrush Turdus plumbeus

- subspecies plumbeus, rubripes, perditus, schistaceus, coryi, ardosiaceus, and albiventris

Now:

- Western Red-legged Thrush Turdus plumbeus

- subspecies plumbeus, rubripes, perditus, schistaceus, and coryi

- Eastern Red-legged Thrush Turdus ardosiaceus

- subspecies ardosiaceus and albiventris

Graphical abstract:

The Red-legged Thrush Turdus plumbeus Linnaeus, 1758 has long been treated as comprised of about six widely distributed Caribbean taxa (as in Ripley 1964, in Volume 10 of Peters’ Check-list). Those from the islands of Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, and Dominica, which form the ardosiaceus Vieillot, 1822 group, however, were originally described as a separate species, and continued to be treated as separate species by Hellmayr (1934). Ridgway (1907) had treated them as constituting three species, the third being rubripes Temminck, 1826 of Cuba and Cayman Brac, and this three-way treatment was recently espoused by del Hoyo and Collar (2016), on the basis of plumage, and for ardosiaceus, song characteristics (Boesman 2016: 310). In addition, relatively deep genetic divergences separate these two groups (Nylander et al. 2008, Batista et al. 2020).

Although there are plumage and bill color differences between Bahamian nominate plumbeus and the other taxa in the rubripes group, and there may be song differences as well, these are not as pronounced as the differences between the ardosiaceus group and the remaining taxa, and the degree of genetic divergence between these groups is evidently not known. In addition, the plumage of schistaceus of eastern Cuba [and that of Cayman Brac coryi (Sharpe, 1902) and the extinct Swan Islands perdita Kirwan & Collar, 2023 (a replacement name for Mimocichla rubripes eremita Ridgway, 1905)] can be interpreted as intermediate between that of Bahamian plumbeus and western Cuban rubripes. Thus, the decision by AviList Core Team (2025) was to enact the two-way split of the more diverged taxa from Hispaniola to Dominica, the ardosiaceus group. However, Proposal 2022-A-03 to NACC (Remsen 2022) to split Turdus plumbeus did not pass due partly to the lack of a published vocal analysis, and scepticism over the specific value of plumage characters in thrushes.

Controversy exists over the subspecific validity of the Dominican population named albiventris (Sclater, 1889), as it was postulated to be the result of pre-Columbian human introduction. However, as Allen (1891) showed when he described it as Mimocichla verrillorum (evidently being unaware of Sclater’s description two years earlier), it has several distinct physical characteristics such as smaller size and especially small bill and wings, greater extent of white on the belly, and more white in the tail, traits that do not seem commensurate with evolution in isolation over such a short period of time as would be the case if human-mediated. These traits were reevaluated and largely confirmed by S.L. Olson in Olson and Ricklefs (2009). In Olson’s opinion, albiventris is such a well-marked subspecies as to make the human introduction hypothesis unlikely. Likewise, Kirwan and Collar (2023) have recently shown that both perdita, formerly of Swan Islands, and coryi of Cayman Brac are likely diagnosable (but sample sizes are small), rather than being consubspecific with western Cuban rubripes.

English names: Given their distributions and the entrenched nature of the name Red-legged Thrush, the names Western Red-legged Thrush for plumbeus s.s. and Eastern Red-legged Thrush for ardosiaceus have been tentatively adopted. The concept of the name Western Red-legged Thrush differs from that used by del Hoyo and Collar (2016), however, as they adopted a three-way split and used Western to refer to their rubripes species, and further discussion is needed.

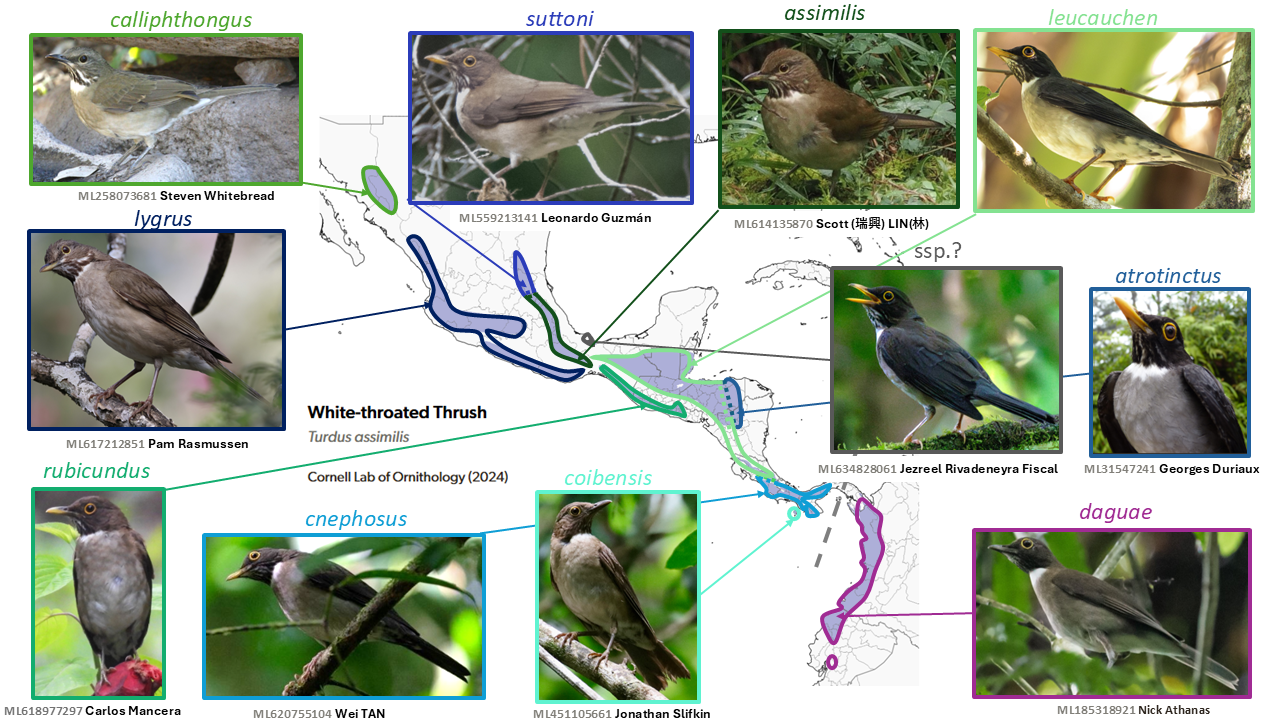

Dagua Thrush Turdus daguae is split from White-throated Thrush Turdus assimilis

Summary: (1→2 species) Another Chocó endemic, the Dagua Thrush, makes its debut as a split from the widespread Mesoamerican White-throated Thrush.

Details: v2025 taxa 28724–28734

Was:

- White-throated Thrush Turdus assimilis

- subspecies calliphthongus, lygrus, assimilis, leucauchen, rubicundus, atrotinctus, cnephosus, coibensis, and daguae

Now:

- White-throated Thrush Turdus assimilis

- subspecies suttoni, calliphthongus, lygrus, assimilis, leucauchen, rubicundus, atrotinctus, cnephosus, and coibensis

- Dagua Thrush Turdus daguae (monotypic)

Graphical abstract:

The taxonomy of New World members of the cosmopolitan thrush genus Turdus is highly complex, and has undergone considerable recent change (with more sure to follow), the Turdus assimilis Cabanis, 1851 complex being no exception. Ripley (1964, in the tenth volume of Peters’ Check-list) considered all the mainly Mesoamerican taxa of assimilis (including daguae) to be conspecific with South American Turdus albicollis Vieillot, 1818. Most recent authors have considered assimilis and albicollis to be separate species, but Collar (2005) again treated all as a single species, while del Hoyo and Collar (2016) treated daguae as a subspecies of albicollis rather than assimilis, and Ridgely and Greenfield (2001) treated daguae as a full species (summarized in Remsen 2021; NACC proposal set 2022-A).

Recent work has underscored the distinctiveness of form daguae Berlepsch, 1897 of far southern Panama to southwestern Ecuador, which was originally described as a species. An initial proposal to NACC, Proposal 2022-A-4, and to SACC, both failed. However, daguae is distinctive in plumage and size (Núñez-Zapata et al. 2016), voice (Boesman 2016: 305), and genetics (Núñez-Zapata et al. 2016), and a follow-up proposal (Johnson and Cooper 2025), Proposal 2025-C-12 to NACC, led to it being considered a full species by NACC (Chesser et al. 2025); furthermore, it has passed a reconsideration by SACC, and is accorded full species status by AviList Core Team (2025). A further issue in the SACC proposal regarding the split of the phaeopygus group is also under consideration, as well as by AviList. See also Subspecies Changes for the resurrection of suttoni. The remaining taxa are divisible into at least two groups, the assimilis and leucauchen groups (Howell and Webb 1995).

English names: The name Dagua Thrush refers to the type locality, the Río Dagua in Colombia. While this by no means encompasses the entirety of the species’ range, it has been used extensively both as a species and group name, and with no obvious competing English names, is adopted by NACC and thus here.

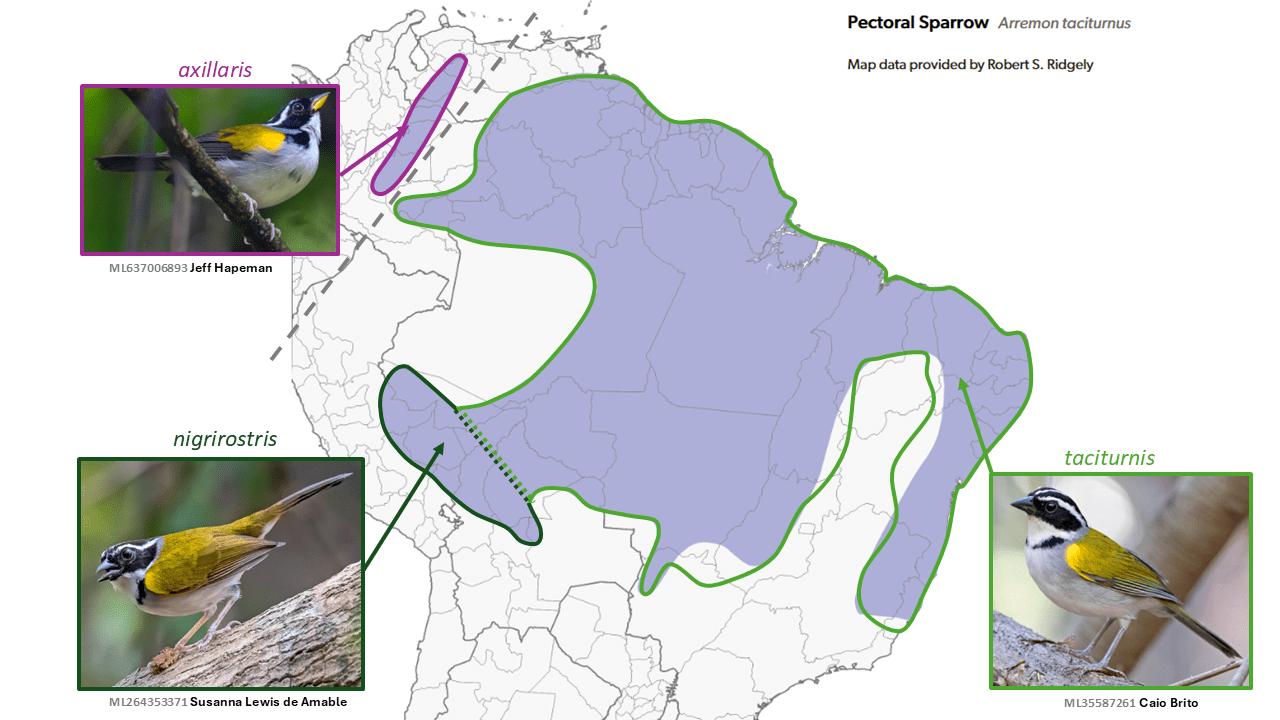

Yellow-mandibled Sparrow Arremon axillaris is split from Pectoral Sparrow Arremon taciturnus

Summary: (1→2 species) The smartly attired Yellow-mandibled Sparrow is now recognized as an endemic to the base of the northern Andes, separate from the mostly Amazonian Pectoral Sparrow.

Details: v2025 taxa 33068–33071

Was:

- Pectoral Sparrow Arremon taciturnus

- subspecies taciturnus, nigrirostris, and axillaris

Now:

- Pectoral Sparrow Arremon taciturnus

- subspecies taciturnus and nigrirostris

- Yellow-mandibled Sparrow Arremon axillaris (monotypic)

Graphical abstract:

Initially described as a species, the yellow-billed taxon axillaris Sclater, 1855 of the foothills region of central Colombia and southwestern Venezuela was long considered a subspecies of the mainly Amazonian Arremon taciturnus Hermann, 1783. Paynter (1970, in Volume 13 of Peters’ Check-list), included not only axillaris but also southeastern Brazilian semitorquatus Swainson, 1838 in taciturnus. Much later franciscanus Raposo, 1997 was described from interior Minas Gerais and Bahia, and both it and semitorquatus are now considered distinct species.

Specific status was accorded to axillaris by del Hoyo and Collar (2016) on the basis of morphological and song differences (Boesman 2016: 361), and shortly thereafter Buainain et al. (2017) published a detailed integrative analysis of the complex, followed later by genetic analysis in Buainain et al. (2022) that showed relatively deep divergence, of a degree more typically associated with species-level taxa than with subspecies. Although the vocal differences require further study, on the basis of these analyses SACC and AviList Core Team (2025) now recognize axillaris as a distinct species.

English names: Given the huge range of Pectoral Sparrow and the familiarity of its English name, there seems no reason to change its English name, while the name Yellow-mandibled Sparrow adequately describes its most obvious morphological difference and has gained some familiarity, so has been adopted by SACC and thus here.

Gray-crowned Ground-Sparrow Melozone occipitalis is split from White-eared Ground-Sparrow Melozone leucotis

Summary: (1→2 species) Another Middle American endemic species is now recognized, with the split of Gray-crowned Ground-Sparrow of southern Mexico and northern Central America.

Details: v2025 taxa 33357–33360

Was:

- White-eared Ground-Sparrow Melozone leucotis

- subspecies occipitalis, nigrior, and leucotis

Now:

- White-eared Ground-Sparrow Melozone leucotis

- subspecies nigrior and leucotis

- Gray-crowned Ground-Sparrow Melozone occipitalis (monotypic)

Graphical abstract:

Three taxa have long been treated as conspecific under Melozone leucotis Cabanis, 1861, with nigrior Miller & Griscom, 1925, occurring locally in central Honduras and northern Nicaragua, occipitalis (Salvin, 1878) of southeastern Chiapas to western El Salvador, and the nominate restricted to the Guanacaste Cordillera, on the Pacific slope of northwestern Costa Rica. Of these, occipitalis was originally described as a species, while nigrior was described later as a subspecies of leucotis; notably, these authors (Miller and Griscom 1925) continued to recognize occipitalis as a full species. Much later, del Hoyo and Collar (2016) also treated occipitalis at the species level.

Sandoval and colleagues recently published a series of papers on bioacoustics of the Melozone leucotis complex (e.g., Sandoval et al. 2016, 2017). Sandoval et al. (2017) further examined morphological and genetic divergence in the complex, and their findings resulted in the decision by AviList Core Team (2025) to split occipitalis as a full species. A follow-up proposal to NACC (Billerman 2023; 2023-C-12) to split occipitalis, however, did not pass, with some voters perceiving the differences as being at the level of subspecies rather than species.

English names: As used by del Hoyo and Collar (2016), the English name White-eared Ground-Sparrow is tentatively retained for Melozone leucotis, although it is the species with the smaller range, while Gray-crowned Ground-Sparrow, used (as Grey-crowned by del Hoyo and Collar 2016) is tentatively adopted for Melozone occipitalis. Given that the crown color of occipitalis is not very pronounced, and that both have equally white auriculars, perhaps other English names would be more suitable.

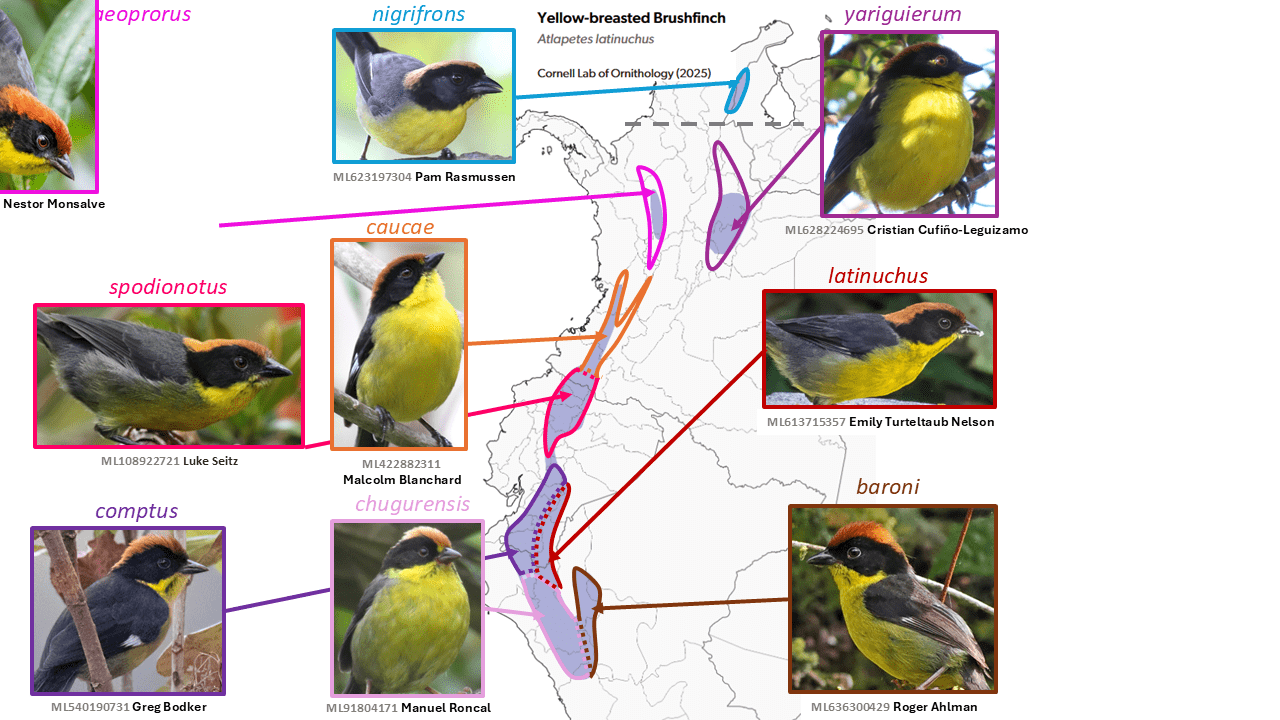

Black-fronted Brushfinch Atlapetes nigrifrons is split from Yellow-breasted Brushfinch Atlapetes latinuchus

Summary: (1→2 species) The brushfinch that frequents feeders in the Perijá Mountains of the Colombia-Venezuela border turns out not to be a Yellow-breasted Brushfinch after all, and is now considered a separate species, Black-fronted Brushfinch.

Details: v2025 taxa 33484–33494

Was:

- Yellow-breasted Brushfinch Atlapetes latinuchus

- subspecies elaeoprorus, caucae, spodionotus, comptus, latinuchus, chugurensis, baroni, yariguierum, and nigrifrons

Now:

- Yellow-breasted Brushfinch Atlapetes latinuchus

- subspecies elaeoprorus, caucae, spodionotus, comptus, latinuchus, chugurensis, baroni, and yariguierum

- Black-fronted Brushfinch Atlapetes nigrifrons (monotypic)

Graphical abstract:

The Atlapetes latinuchus (Du Bus de Gisignies, 1855) complex, distributed in several subspecies from the Venezuela/Colombia border southward in the Andes to central Peru, was formerly included within the larger species Atlapetes rufinucha (d’Orbigny & de Lafresnaye, 1837) (as by Paynter 1970, in Volume 13 of Peters’ Check-list). The northernmost form, from the Perijá Mountains, was described relatively late, as Atlapetes rufinucha nigrifrons Phelps & Gilliard, 1940. Significantly, Phelps and Gilliard (1940) stated “[t]his new subspecies is not closely allied to any particular race of A. rufinucha. Its broad, solid black forehead distinguishes it from all others.”

García-Moreno and Fjeldså (1999) showed in an early mtDNA paper that rufinucha and the latinuchus complex are non-sister, a result that has more recently been strongly corroborated (Sánchez-González et al. 2015), leading to the treatment of latinuchus as an independent, still highly polytypic species. Within the genus Atlapetes as then constituted, nigrifrons was found to be preoccupied by Atlapetes torquatus nigrifrons (Chapman, 1923), and the name was replaced by Atlapetes latinuchus phelpsi Paynter, 1970. However, with the more recent move of the torquatus clade to Arremon, there remains no need for Paynter’s replacement name, and nigrifrons is again the name in force for the Perijá form under discussion here (Donegan 2006, SACC proposal 222).

Donegan and Huertas (2006) suggested, on the basis of a phylogeny using plumage characters, that nigrifrons was misplaced in the latinuchus complex and belongs in a clade with Atlapetes melanocephalus (Salvin & Godman, 1880) of the Santa Marta range and the intermediate “Perijá bird”; however, plumage characters may carry misleading phylogenetic signal in this group. An in-depth study including a vocal analysis by Donegan et al. (2014) further confirmed that nigrifrons is much more vocally similar to melanocephalus and albofrenatus than any of these are to Atlapetes latinuchus. Unpublished phylogenetic data (by D. Cadena) are said to confirm that nigrifrons is not sister to latinuchus. As suggested by Donegan et al. (2014), it may be more closely related to Atlapetes albofrenatus (Boissonneau, 1840), although genetic data are lacking. In addition, some rather intermediate-looking specimens (called the “Perijá bird”) are known that may indicate introgression between nigrifrons and albofrenatus, or they may be an undescribed subspecies of albofrenatus. The latter suggestion received support from the observation of non-intermediacy of mantle color differences and apparent elevational replacement, with nigrifrons occurring at higher elevations.

On the basis of the above, del Hoyo and Collar (2016) considered nigrifrons a separate species. An earlier proposal to SACC to split nigrifrons (Donegan), did not pass and was eventually withdrawn. As nigrifrons is clearly not correctly assigned to latinuchus, it is tentatively accorded species status by AviList Core Team (2025), although further work may show it is better considered a subspecies of albofrenatus.

English names: As used by del Hoyo and Collar (2016), Yellow-breasted Brushfinch is tentatively retained for the widespread, polytypic species Atlapetes latinuchus s.s., while Black-fronted Brushfinch is used for Atlapetes nigrifrons. The latter name is apt, highlighting the taxon’s most distinctive feature, especially given that the name Perija Brushfinch is not available, being already in wide use for Arremon perijanus.

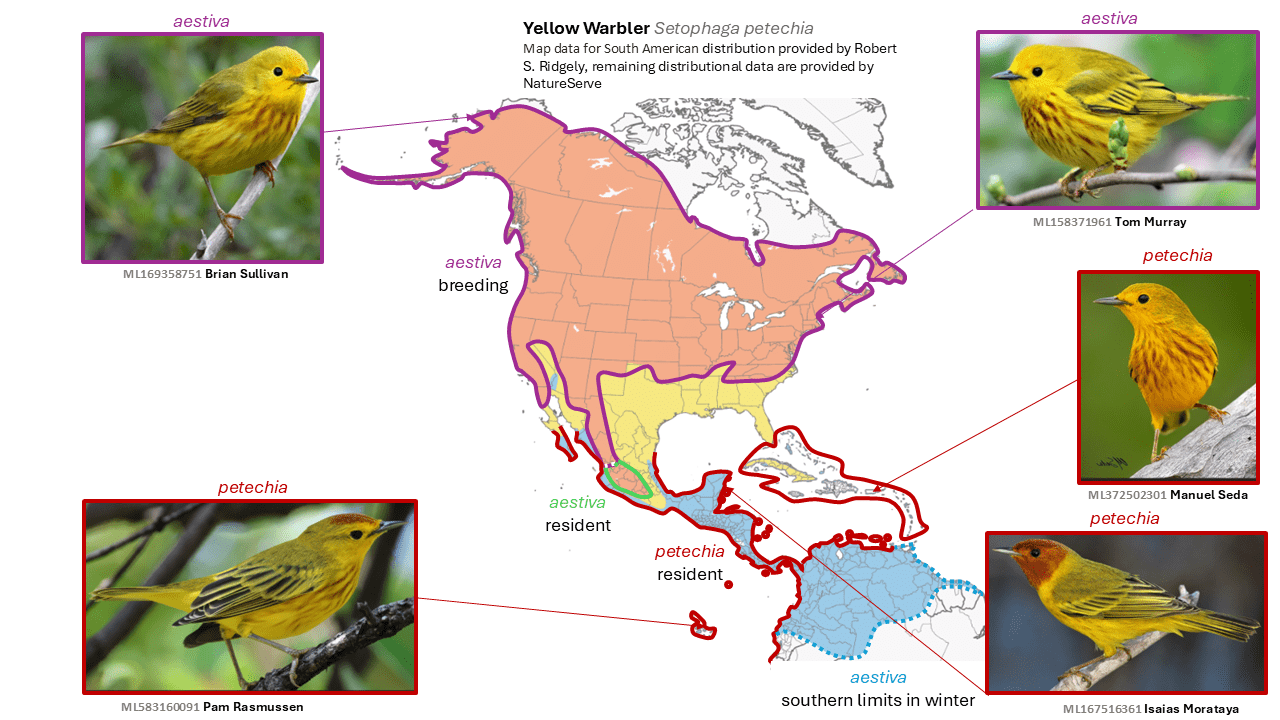

Northern Yellow Warbler Setophaga aestiva and Mangrove Yellow Warbler Setophaga petechia are split from Yellow Warbler Setophaga petechia

Summary: (1→2 species) With the two-way split of Yellow Warbler, birders in Neotropical mangroves will need to carefully document the warblers they are likely to encounter there.

Details: v2025 taxa 34087–34130

Was:

- Yellow Warbler Setophaga petechia

- subspecies rubiginosa, amnicola, aestiva, morcomi, sonorana, dugesi, oraria, bryanti, erithachorides, chrysendeta, paraguanae, cienagae, castaneiceps, rhizophorae, xanthotera, aequatorialis, peruviana, aureola, rufivertex, armouri, flavida, eoa, gundlachi, albicollis, cruciana, bartholemica, melanoptera, ruficapilla, babad, petechia, alsiosa, rufopileata, obscura, and aurifrons

Now:

- Northern Yellow Warbler Setophaga aestiva

- subspecies rubiginosa, amnicola, aestiva, morcomi, sonorana, and dugesi

- Mangrove Yellow Warbler Setophaga petechia

- subspecies oraria, bryanti, erithachorides, chrysendeta, paraguanae, cienagae, castaneiceps, rhizophorae, xanthotera, aequatorialis, peruviana, aureola, rufivertex, armouri, flavida, eoa, gundlachi, albicollis, cruciana, bartholemica, melanoptera, ruficapilla, babad, petechia, alsiosa, rufopileata, obscura, and aurifrons

Graphical abstract:

A comprehensive proposal (Browning 2018, Proposal 2018-C-2 to NACC), which did not pass, forms the basis for much of the following summary; in turn, much of that proposal is based on Browning (1994). The sheer number of taxa and geographic distances involved have defeated most attempts to gain an understanding of the taxonomy of the Yellow Warbler complex. However, a selection of the many studies impinging on this matter are briefly discussed below.

Long treated as at least two species, the many taxa of Yellow Warbler Setophaga petechia (Linnaeus, 1766) (of which 12 that are currently recognized in AviList v2025 were originally described as full species) were united by AOU (1945). This followed the convincing demonstration by Aldrich (1942) of gradients between characters supposedly diagnostic of the tropical petechia group vs. the north-temperate-breeding aestiva (Gmelin, 1789) group.

Although they are broadly allopatric in the US, ranges of apparently resident taxa of both groups are in close proximity in west-central Mexico, albeit strongly segregated by habitat (upland for aestiva group vs. mangroves for the broad-sense petechia group, here used to indicate all sedentary coastal subtropical to tropical taxa). They are also very commonly in contact in the nonbreeding season through much of the range of the petechia group, including in mangroves, where the aestiva group commonly winters. The single-species treatment was maintained by Lowery and Monroe (1968, in Volume 14 of Peters Check-list), although not adhered to by all (e.g. Ridgely 1976, who treated erithachorides and petechia as separate species).

An early mtDNA phylogeny (Klein and Brown 1994) found deep divergence between the temperate zone-breeding aestiva group which breeds mostly in wooded riparian habitats, especially willows, and the subtropical- to tropical-breeding, mostly mangrove-inhabiting broad petechia group, including the erithachorides group (Baird, 1858). Although Klein and Brown (1994) did not consider their results to demonstrate that more than one species is involved, they were interpreted by Ridgely and Greenfield (2001) as supporting at least a two-species treatment, and in this Ridgely and Greenfield were followed by IOC (from version 2.1 onward). In addition, Hilty (2003) treated both petechia s.s. and erithachorides as separate species, citing two genetic studies.

Wiedenfeld (1991) showed that the inclusive Dendroica petechia s.l. does not follow either Bergmann’s or Allen’s rules, with most tropical populations being larger overall than temperate-breeding ones. However, wing length varied with latitude, as earlier shown by Aldrich (1942).