Safeguarding the Songs of Spring: The Outsize Value of the Five Great Forests

[BIRD CHIRPS]

VIVIANA RUIZ GUTIERREZ: When we think of spring, we think of a lot of things. We think of life coming back in different forms.

[STORM]

We think of rain.

[RAINFALL]

We think of flowers. But for most people, it really means birdsong.

[BIRDS SINGING]

So imagine what would it sound like and feel like if birds didn’t come back. I’ve always said if birds could speak, I wouldn’t have a job. Birds are trying to tell us a lot. Ever since 1970, we’ve lost about 3 billion birds. And the most recent State of the Birds suggests that one in four species are facing extinction in North America alone.

One of the main reasons for the declines for migratory birds can be linked to habitat loss and degradation. And we always had a hard time deciding which are the most important areas that we should be investing in protection, because we haven’t been able to get a big picture overview of how these birds that migrate thousands of miles, where they spend their time, when are they spending most of their time there, and what are those species that are relying on these specific places.

We have known that Latin America is important for a lot of migratory birds, but what we didn’t know until now is how important individual places are. What’s very exciting is for the first time, we’re able to really quantify for each individual species and across all species, the importance of the Five Great Forests of Mesoamerica.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

ANNA LELLO-SMITH: I think that birders in North America have this general idea and knowledge that the birds that they love to watch in the spring and summer leave and they go to Central and South America. But I think it doesn’t really hit home for people until they’re here just really where their birds are going and how abundant they are.

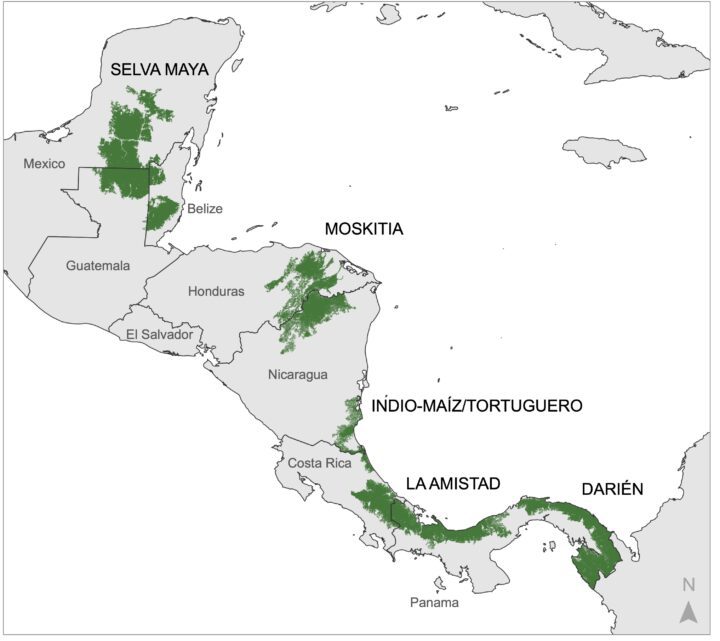

The Five Great Forests of Mesoamerica are the last large blocks of tropical forest remaining in Mesoamerica. They are the Selva Maya of Belize, Mexico, and Guatemala. The Moskitia of Honduras and Nicaragua. Indio-Maíz Tortuguero, which crosses Nicaragua and Costa Rica. La Amistad of Costa Rica and Panama, and then the Darién, which is between Panama and Colombia.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

ANNA LELLO-SMITH: [SPEAKING SPANISH] Magnolia, too.

MARCIAL CORDOVA: Magnolia Warbler.

HECTOR LÓPEZ: Magnolia?

ANNA LELLO-SMITH: [SPEAKING SPANISH] Yes.

We have known anecdotally that these forests are super important for migratory birds, but we, until recently, weren’t able to actually quantify how important these forests are for populations of those species. And thanks to eBird, which is the largest participatory science database in the world, we’re now able to put numbers to what we already knew, which is that these forests are really important for birds.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

VIVIANA RUIZ GUTIERREZ: Once we started getting a lot of data in eBird, it became clear that the possibilities were going to be endless because we’re able to really take a big picture look and assess where are they spending most of their winter, where are they breeding. And we’re able to do that across every single species in North America now.

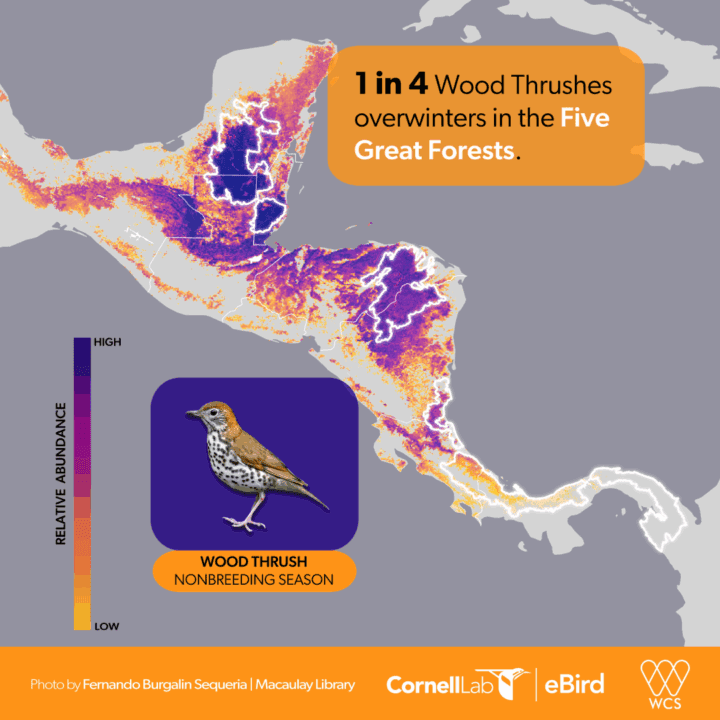

Out of the 314 migratory bird species we studied, we found that over half of those species use the Five Great Forests. If we take a look at Wood Thrush, which is in steep decline once they leave their breeding grounds in the Eastern US and Canada, one in four individuals ends up in the Five Great Forests, remaining there up to 4 to 5 months.

We see a similar pattern in the Broad-winged Hawk. As individuals migrate south from their breeding grounds in Canada and the Eastern US, one in three individuals stop in the forests before continuing their journey to South America.

The same is true for the Cerulean Warbler, whose population has declined by 72% since 1970. After they depart the Midwest and Appalachia, one in three stops in the Five Great Forests before they migrate south to the Andes.

When we combine the top 40 migratory bird species that use these forests and follow their migration across a full annual cycle, we really see the Five Great Forests light up like a beacon. It’s incredible to see how concentrated they are in these forests and then how broadly they distribute once they’ve returned to the North American breeding grounds in the spring. And that speaks volumes about how important they are, how much we rely on what happens there, but also of that linkage that we were never able to make before, about that shared stewardship that we have with these forests.

ANNA LELLO-SMITH: We found that migratory birds connect the Five Great Forests to Texas Hill Country, to the Lower Mississippi Valley, to the Appalachian Mountains, New York and Massachusetts and Connecticut, as well as large parts of Eastern Ontario, and then also to the Upper Midwest.

The forests are facing some really urgent threats. They’re being decimated by illegal cattle ranching and forest fires. In just the last 15 years, the northern three forests have lost a third of their forest cover. And we can bring back the forest that’s been lost. But that means doing forest restoration on a massive scale, which requires a lot of resources.

The people who live within the Five Forests are really the heroes in protecting the forest. They are conducting forest patrols to protect the forest from further deforestation. They’re also doing incredible work to prevent forest fires. And then these same communities are also doing on the groundwork of restoring forest that’s been lost or degraded.

CÉSAR PAZ: [SPEAKING SPANISH] Something very important is the engagement and participation of the community. Together with the community we decide and analyze what is the best area for us to restore and start our restoration work.

ANNA LELLO-SMITH: Some of these same local communities have constructed native tree nurseries, where they collect seeds of native trees from the surrounding forest, and they plant them and take care of them until they get to be seedlings that can be planted in old clearings and cattle pastures.

FELISA NAVAS: [SPEAKING SPANISH] The theme of the workshops is that we have to protect our forests and do things sustainably in our community. In a few years, I think all these pasture lands will no longer be the same. And also there will be more birds present here.

ANNA LELLO-SMITH: One of the really cool things is that a lot of the eBird data was generated by people who live in the Five Great Forests.

EMNETT MARROQUÍN: [SPEAKING SPANISH] Look at that Magnolia. It’s just there. Look at the field mark under its tail. It has black on it.

ANNA LELLO-SMITH: Chalo has created this incredible team of young local men and women to identify birds by sight and sound, and then to monitor them.

CATALINA LÓPEZ: [SPEAKING SPANISH] I never imagined that at some point I was going to go out and give talks and tell the new children about what we should take care of. I would like many more people to get involved and to also be part of all this that we are doing.

MARCIAL CORDOVA: [SPEAKING SPANISH] How beautiful to know that what we are doing matters. It is making the world aware of the importance of conserving and maintaining our forests. So, I think that’s what impacts you and makes you want to continue working and contributing for the benefit of all humanity. Not just for me, not just for my son, but for everyone. This is something that has motivated me to keep going.

ANNA LELLO-SMITH: Seeing all of the people who love these forests so much and are so dedicated to protect what they have and to restore what’s been lost, that gives me hope.

We need people who maybe have never heard of these forests to really understand how connected they are to us in North America, and to support the people who are there on the ground, fighting every day to protect them.

VIVIANA RUIZ GUTIERREZ: Just think about the possibility of connecting with those efforts to make sure that year-round we can enjoy birds here, they can enjoy birds there, and really have migratory birds start to come back.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

End of Transcript

Every spring our forests and parks fill with the delightful songs and colors of warblers, thrushes, and orioles arriving from southern forests that sustain them through the winter months. These birds rely not only on forests in the United States and Canada, but also on forests to the south that are increasingly threatened by illegal deforestation, forest fires, and rising temperatures.

A new study from the Wildlife Conservation Society and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology found that the forests of Central America are indispensable lifelines for dozens of migratory bird species that link the Americas.

Using the more than 2 billion observations shared by birders around the world with the Cornell Lab’s eBird program, scientists created precise models of where individual species concentrate week by week. These models can now zoom down to areas roughly the size of Central Park—small enough to guide protection efforts to specific valleys, ridges, or forest groves that matter most for declining species.

Inspiring—and Sobering—Results

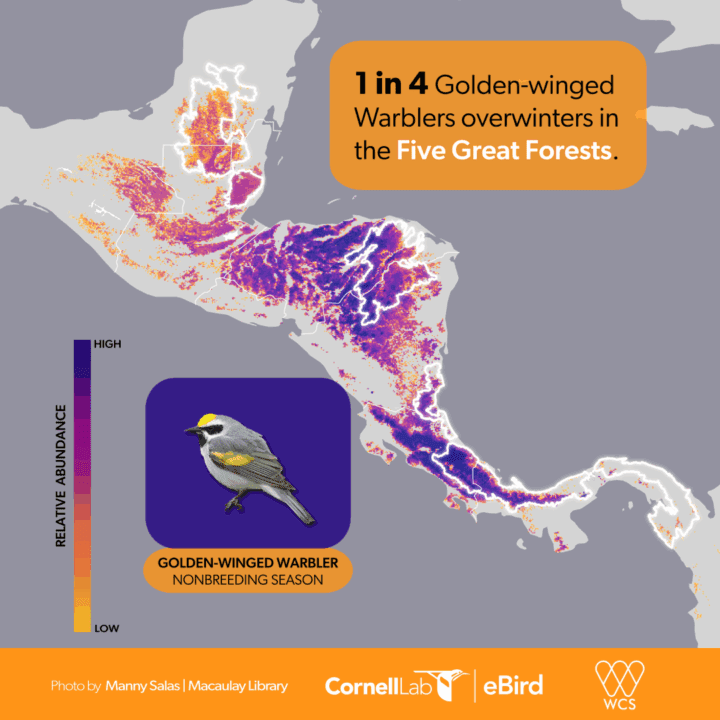

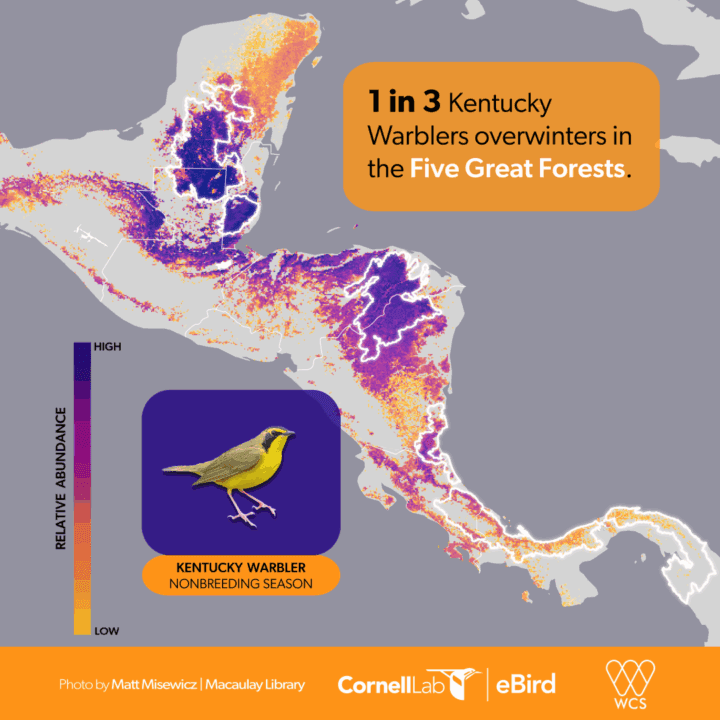

Scientists found that the Five Great Forests collectively support anywhere between one-tenth to one-half of the global populations of 40 migratory species.

Yet three of the Five Great Forests have lost nearly a quarter of their area in just the past 15 years. This threat is made worse by poverty, land-tenure insecurity, drug trafficking, and climate change.

The density of birds concentrated in the Five Great Forests means every acre that can be protected will safeguard a disproportionate number of birds.

A Vision for the Five Great Forests

Together, the Five Great Forests of Mesoamerica form an area only the size of Virginia—yet they offer a home away from home to billions of migratory songbirds and serve as critical wintering grounds and stopover sites.

That’s why the Cornell Lab is partnering with the Wildlife Conservation Society to provide the cutting-edge data that powers on-the-ground conservation to protect and restore the Five Great Forests and the familiar species that rely on them.

Our goal is to harness the power of eBird models to identify where investments in restoration and forest protections are most needed—advancing the vision of the Five Great Forests Initiative to secure 10 million hectares of permanently protected forests and restore 500,000 hectares of degraded lands.

Through our collaboration with the Wildlife Conservation Society, this effort is carried out hand in hand with Indigenous and local communities, uniting state-of-the-art science with on-the-ground stewardship to strengthen livelihoods and ensure that both people and nature thrive.

Join Our Email List

The Cornell Lab will send you updates about birds, birding, and opportunities to help bird conservation. Sign up for email and don’t miss a thing!

Golden-cheeked Warbler by Bryan Calk/Macaulay Library