Cornell Lab Annual Report 2023

Download the Full ReportI am thrilled to share this annual report to thank you for your steadfast support, and to illustrate how your generosity is transforming our work.

Ian Owens, Executive Director of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Together We Act, the theme of our report, is about the power of partnership—and one of our most important partners is you.

Together We Protect

A new era for conservation is underway. It’s powered by people and by big data—a movement spurred in equal measure by a love of birds and wildlife and by new advances in technology.

The Cornell Lab is a hub where people and technology come together. It’s where the Lab’s tech teams build the platforms for individuals around the world to enjoy birds and share their observations. It’s where our scientists move these contributions into massive number-crunching analyses to pinpoint where species are declining, and surface solutions.

The key now is to move ideas into worldwide action, to deliver the customizable insights that any person, community, land manager, or policy maker can use to protect nature, locally and internationally. Beyond, through the power of storytelling, we will amplify the voices of those who are rallying for conservation, and combine science with the cinematic beauty of wildlife to inspire decisions to benefit nature.

Together, we are working urgently to counter the steep declines in birds and other wildlife. Together, our opportunity is boundless.

Together We Discover

We accelerate discovery with pioneering research and technology. More than that, we share our passion, tools, and knowledge with others to spark the next discoveries around the world.

Here at the Cornell Lab, scientists and engineers develop techniques to reveal the invisible: elephants rumbling in tropical forests; millions of insects strumming in the rainforest; birds migrating under cover of darkness; the history of a species, written in DNA.

With bioacoustics, radar, and genetic analyses, we have the capability to monitor the heartbeat of the planet. But we can’t do it alone.

By teaching the next generation of conservation leaders, and by bringing tools and technology to new communities and collaborators, together we foster the skills and capacity to study and protect wildlife, from whales in Hawaii to penguins in Antarctica.

Together We Transform

Moving the needle toward a healthier world means helping people connect with their surroundings. People will take action for what they understand, care about, and love.

The Cornell Lab supports millions in these actions when they carry the Merlin Bird ID app with them everywhere, enjoying instant access to information about birds and nature in 17 languages and counting. Beyond that, we ensure science and discovery take root in learners of every age through Bird Academy and K–12 education. And we help many more take action through international participatory science projects like Global Big Day, Great Backyard Bird Count, NestWatch, and Project FeederWatch.

This model goes far beyond ideas and apps. You can find the beating heart of a movement in the groups, organizations, and communities that are partnering with the Lab wherever birds and nature inspire the change the world needs.

Why We Support the Lab

Ford and David Schumann cannot remember a time they didn’t possess a keen appreciation for birds and nature.

Today, through the Robert Schumann Foundation, the brothers continue to support the Cornell Lab. Like their late father—one of the very first supporters who helped get eBird off the ground—they seek to change hearts and minds on behalf of birds. “We often support the Lab’s Center for Conservation Media,” David explains, “because they have the ability to influence lawmakers and communities to change and take action.”

K. Lisa Yang believes in the power of discovery, which opened her eyes to the Cornell Lab.

A conservationist and self-described “investor for the future,” Lisa saw the potential of the Lab’s bioacoustic research on a chance open-house visit during Migration Celebration. Envisioning how bioacoustics can inform data-driven decision-making, Lisa stepped in and endowed the K. Lisa Yang Center for Conservation Bioacoustics. With greater resources, the Center has pioneered the analysis of massive datasets to yield powerful insights about global wildlife health.

Carlyn and Tom Jervis fell in love at Cornell. With birds—and each other.

Life took Tom and Carlyn many places, yet a piece of their hearts remained in Sapsucker Woods. “Reading Living Bird, we learned about everything the Lab was doing, so when we could afford to be donors, we started contributing,” says Tom. They’re now key supporters of the Coastal Solutions Fellows program. “We wanted to direct our giving to something research-oriented… recognizing that there are complex social, economic, and political dynamics to conservation,” explains Carlyn.

Financial Report

2023 Fiscal Year:

July 1, 2022, to June 30, 2023

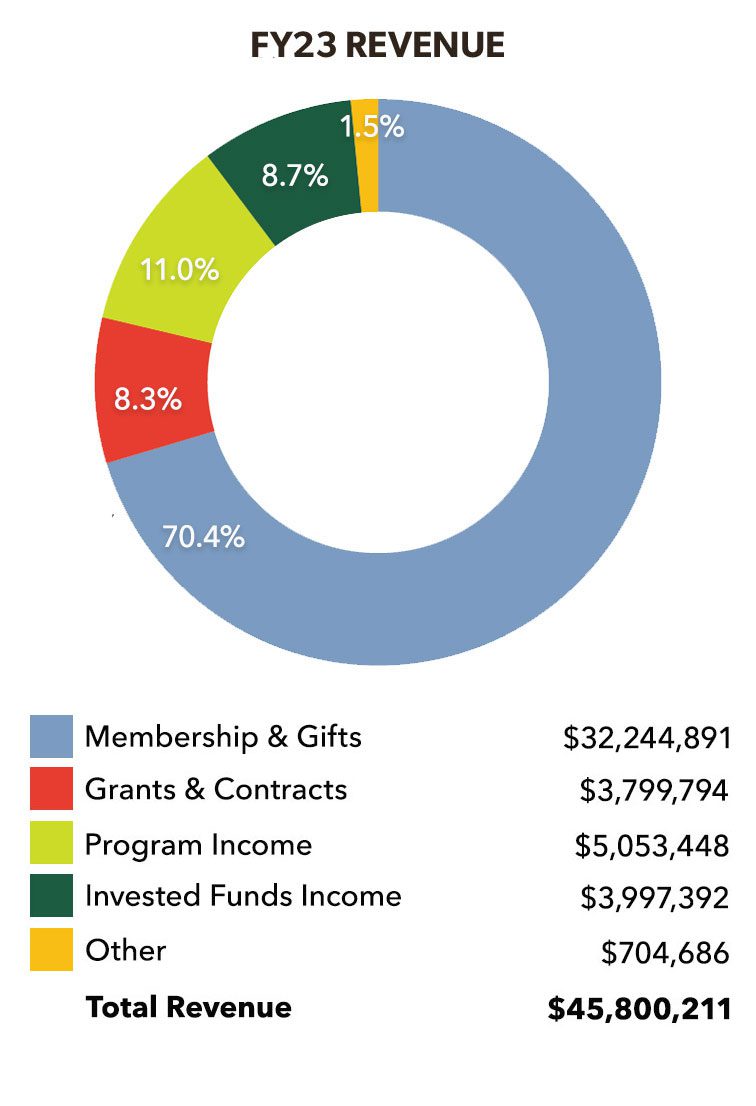

Thank you for supporting the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. In fiscal year 2023, thousands of members and donors provided more than 70% of our annual revenue, a total of $32.2 million that expands our capacity to promote global conservation through research, education, and participatory science.

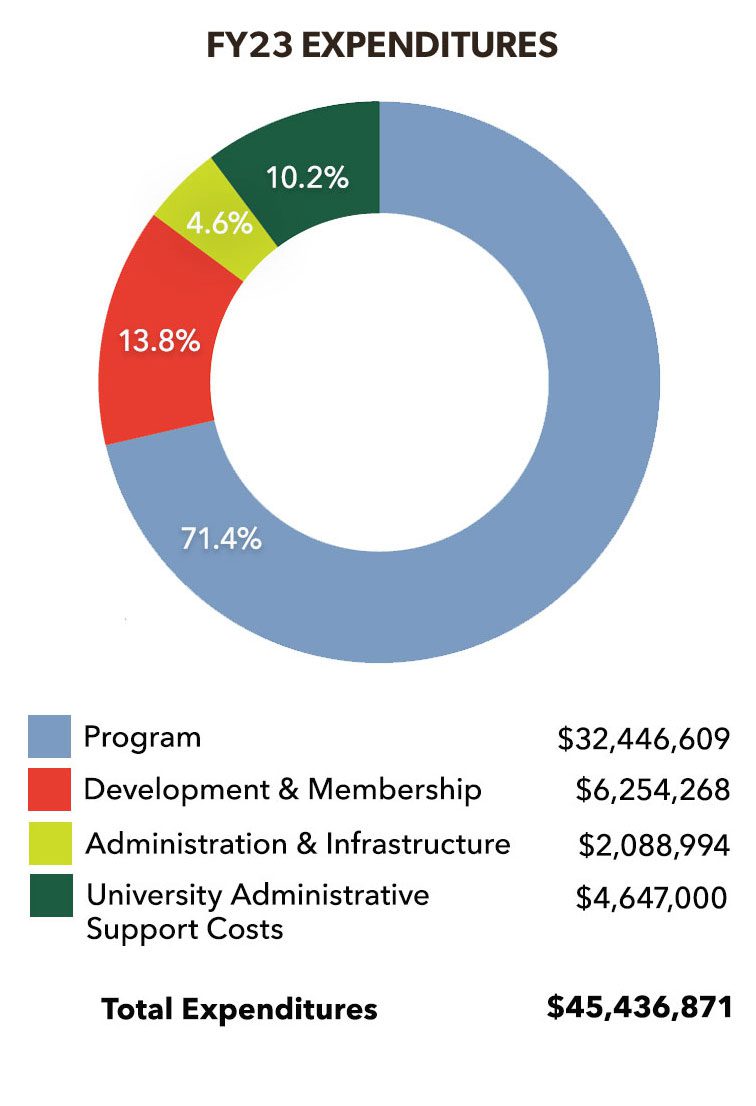

As a mission-driven nonprofit organization nested within a world-class academic research institution, the Cornell Lab leverages our strength to provide information, tools, and inspiration to people and partners around the world to help reverse the decline in birds and biodiversity.

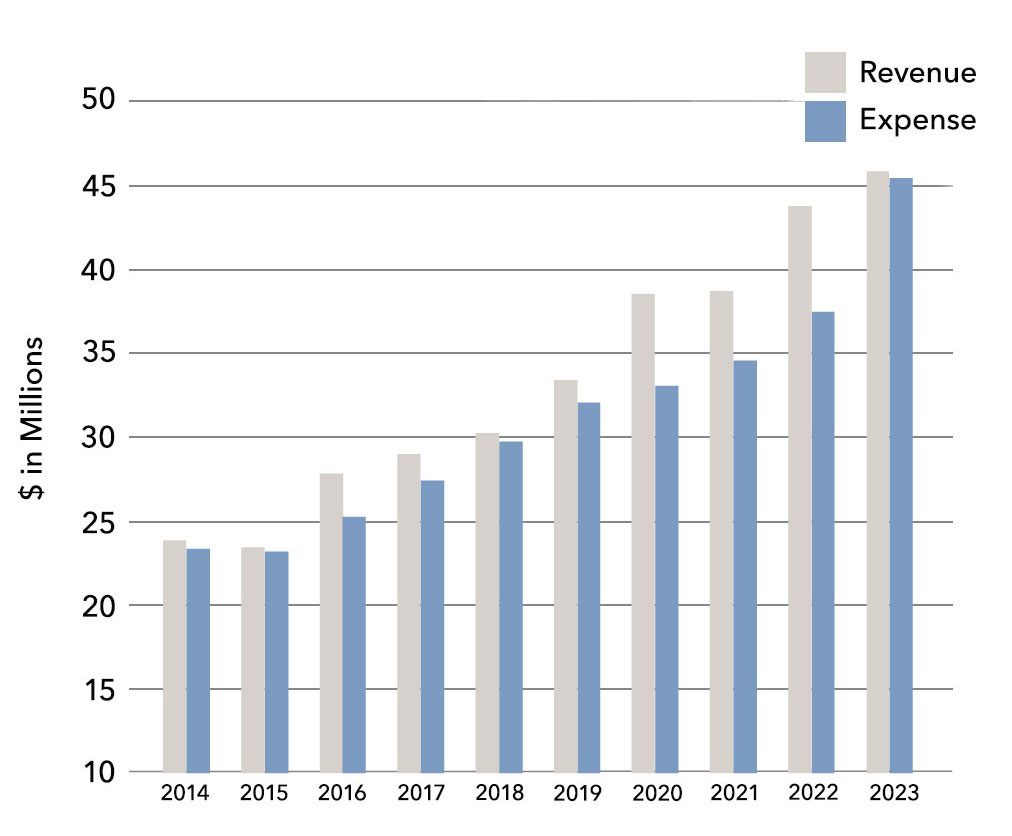

Revenue and Expenditures Over Time

The bar chart depicts healthy growth over the past 10 years with revenues exceeding expenditures, allowing the Lab to continually expand and strengthen our vital research, education, and conservation efforts.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, strong philanthropic support combined with a minimal increase in expenses resulted in an uncommon surplus of funds for several years. As we returned to pre-pandemic levels of activity this year, we have invested these surpluses in people, technology, and innovative ideas to accelerate our work.

We’re pleased to include a downloadable list of our Sapsucker Woods Society members and honor and memorial tributes here.

Download previous annual reports here:

2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009.

Join Our Email List

The Cornell Lab will send you updates about birds, birding, and opportunities to help bird conservation. Sign up for email and don’t miss a thing!

Golden-cheeked Warbler by Bryan Calk/Macaulay Library