ARCHIBALD BIOLOGICAL RESEARCH STATION ORNITHOLOGIST: One of the questions that every student who comes into this lab asks me is, "You guys have been doing this for 44 years, what questions still remain?" Every time you answer a question you raise five more.

JOHN FITZPATRICK, ORNITHOLOGIST: The more you study a system like this, the less you know about it.

NANCY CHEN, SCIENTIST: Did you ever think that we would be sequencing the bird's genome?

FITZPATRICK: No, I didn't know what the word 'genome' meant in 1972.

FITZPATRICK: Who just came in?

CHEN: Hot silver dash, hot…. [refers to band colors]

FITZPATRICK: Hot lime? That's not the bird we're missing, is it?

CHEN: There's purple dash number or...

FITZPATRICK: Green lime silver dash, I know who that is.

CHEN: This is a catchphrase for our overall project: "We're studying the genomics of extinction." The idea is, we're trying to understand what happens to the genetics of a population as it becomes so small in size, and eventually goes extinct. The ultimate kind of 10-year plan is to use the scrub-jays as a model system for trying to understand what happens when population sizes become really small.

FITZPATRICK: [Imitating alarm calls] Psh, phs, psh, psh, psh, psh, psh.

CHEN: Oh! I just heard wings, here we go! I study population genomics, but I would call myself an evolutionary biologist first, and then an ornithologist second.

CHEN: Is he gonna come? See, I have finally learned how to hold onto peanuts... took several years. In middle school, I wanted to be a field biologist, mostly because I loved animals and wanted to work with animals. I didn't really develop an interest in birds until high school, and even then I had no idea that I would be doing this. I want one on my head!

CHEN: What we're doing right now is collecting blood. These samples form the whole basis of my project. Without the DNA samples I would have nothing to analyze.

CHEN: The beauty of the Florida Scrub-Jay is, it's been studied for so long. There's 40 years' worth of data. We know everything about every bird. We know when it was born, how many offspring it had, how many offspring their offspring had, we have measures of habitat quality, territory size, there's so much data! And so my goal is that if we add on genomics for all of these birds for which we have complete life histories, then we can actually start to ask a bunch of questions that no one else was able to ask before. It's pretty exciting.

CHEN: Somebody asked me the other day -- well, there we go! [bird lands on head] So our goal for the next couple years is to really, truly understand what is going on with these birds. Can we identify genes in this bird, on my head, that can help explain how long he's going to survive and how many nestlings he produces over his lifetime. I mean, this is kind of one of the most fundamental questions in evolutionary biology: what is the genetic basis for fitness, why do some individuals do better than others? We don't know, and our goal is to use all the information we have with these birds to try to answer that.

FITZPATRICK: Purple purple and purple..

CHEN: Purple- orange, got it. The joy of discovering something new, there really isn't something that comes close to that. Discoveries don't come often, but that's okay because when it does happen when you find a new result, it's really exciting. [CHEN: So we're missing the female and purple lime.] CHEN: When I decided to go to grad school I wanted to do some combination of lab work and fieldwork, and it turns out now I spend probably seventy percent of my time in front of a computer programming. That was a bit of a surprise. It's good for me to come reacquaint myself with the birds, get re-excited about the biology. Plus I just love it here. There's no other place like this on Earth.

CHEN: If you want to understand what are the genes that influence survival and reproduction, I'm not going to be able to measure that in the lab. Ow, that actually hurts. [jay pecks at her hand]

End Transcript

Coastal SolutionsRevitalizing the Pacific Flyway

Coastal SolutionsRevitalizing the Pacific Flyway Conservation MediaAmerica’s Imperiled Arctic Wilderness

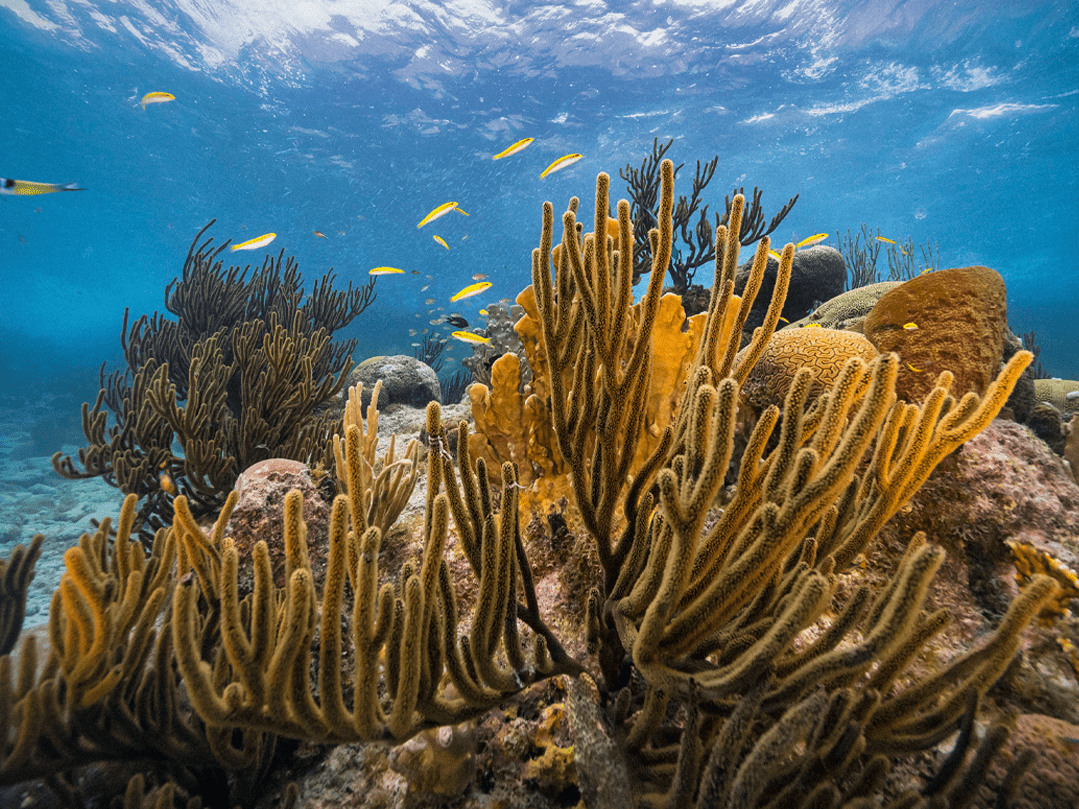

Conservation MediaAmerica’s Imperiled Arctic Wilderness Conservation in ActionIf This Reef Could Talk

Conservation in ActionIf This Reef Could Talk Conservation in ActionHow We Use Sound to Help Protect Elephants from Poaching

Conservation in ActionHow We Use Sound to Help Protect Elephants from Poaching Conservation in ActionCalifornia Protects Tricolored Blackbird After eBird Data Help Show 34% Decline

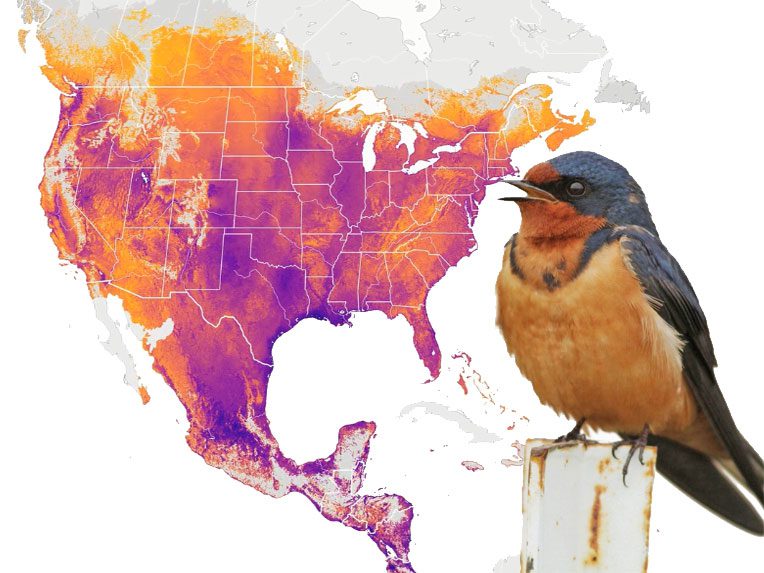

Conservation in ActionCalifornia Protects Tricolored Blackbird After eBird Data Help Show 34% Decline Conservation in ActionCoastal Solutions: Building a Bold New Community to Address the Shorebird Crisis

Conservation in ActionCoastal Solutions: Building a Bold New Community to Address the Shorebird Crisis Conservation MediaBirds-of-Paradise Help Inspire Conservation of Forests in West Papua

Conservation MediaBirds-of-Paradise Help Inspire Conservation of Forests in West Papua